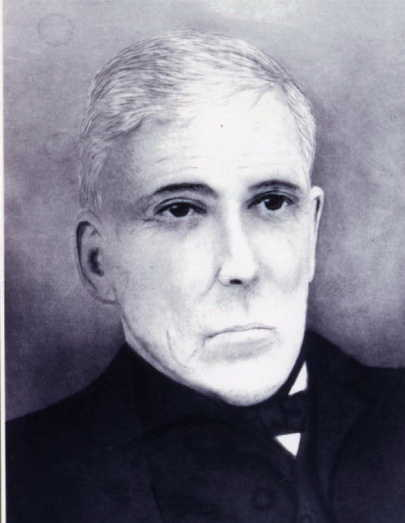

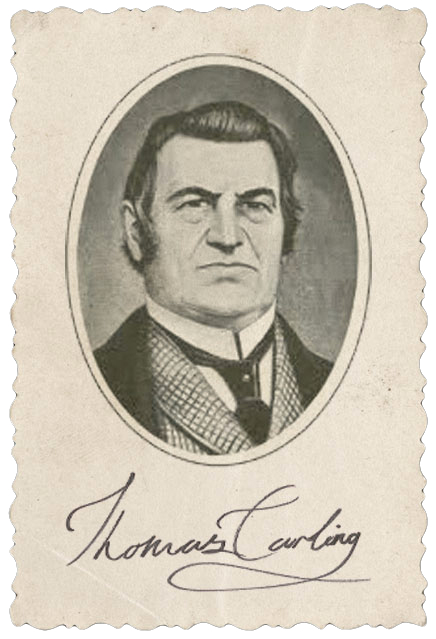

Today is the birthday of Alexander Keith (October 5, 1795–December 14, 1873). He was born in Scotland, where he was trained as a brewer. He settled in Canada, specifically Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 1820, where he founded the Alexander Keith Brewery.

Here’s his biography from his Wikipedia page:

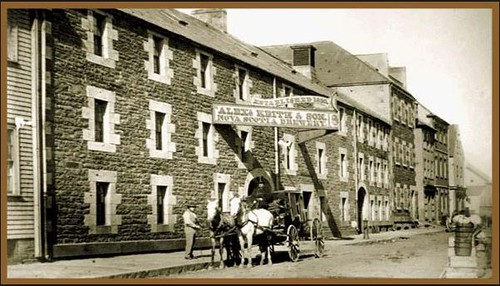

Keith was born in Halkirk, Caithness, Highland, Scotland, where he became a brewer. He immigrated to Canada in 1817 and founded the Alexander Keith’s brewing company in Halifax, Nova Scotia in 1820, moving to a three-storey building on Hollis Street at Lower Water in the downtown area in 1820. Keith had trained as a brewer in Edinburgh and London. His early products included ale, porter, ginger wine, table and spruce beers.

Alexander Keith served as mayor in 1843 and in 1853-54 and president of the Legislative Council (provincial parliament) from 1867 to his death in 1873.

Throughout his career Keith was connected with several charitable and fraternal societies. He served as president of the North British Society from 1831 and as chief of the Highland Society from 1868 until his death. In 1838 he was connected with the Halifax Mechanics Library and in the early 1840s with the Nova Scotia Auxiliary Colonial Society. Keith was also well known to the Halifax public as a leader of the Freemasons. He became Provincial Grand Master for the Maritimes under the English authority in 1840 and under the Scottish lodge in 1845. Following a reorganization of the various divisions in 1869, he became Grand Master of Nova Scotia. There are four masonic lodges named in his honour: Moncton, New Brunswick, and Halifax, Stellarton, and Bear River in Nova Scotia.

Alexander Keith died in Halifax in 1873 and was buried at Camp Hill Cemetery at the corner of Spring Garden Road and Robie Streets. His birthday is often marked by people visiting the grave and placing beer bottles and caps on it (or, less frequently, cards or flowers).

And this more thorough biography is from the Dictionary of Canadian Biography:

KEITH, ALEXANDER, brewer and politician; b. 5 Oct. 1795 in Caithness-shire, Scotland, son of Donald Keith and Christina Brims; d. 14 Dec. 1873 in Halifax, N.S.

When Alexander Keith was 17, his father sent him to an uncle in northern England to learn the brewing business. Five years later, when Keith migrated to Halifax, he became sole brewer and business manager for Charles Boggs, and he bought out Boggs’ brewery in 1820. On 17 Dec. 1822 he married Sarah Ann Stalcup, who died in 1832. On 30 Sept. 1833 he married Eliza Keith; they had six daughters and two sons. One son, Donald G. Keith, became a partner in the brewing firm in 1853.

In 1822 Keith moved his brewery and premises to larger facilities on Lower Water Street and in 1836 he again expanded, building a new brewery on Hollis Street. In 1863 he began construction of Keith Hall which was connected by a tunnel to his brewery. Keith Hall, now occupied by Oland’s Brewery, is in the Renaissance palazzo style, with baroque adornments, pillars of no particular style, and a mansard roof. This peculiar combination of styles resulted from the fact that the designs were probably derived from books with plans of buildings in Great Britain and the United States. Keith’s appointment as a director of the Bank of Nova Scotia in 1837 along with William Blowers Bliss is an indication of his importance in the Halifax business community. Beginning in 1837, he also served as a director, at various dates, of the Halifax Fire Insurance Company. In 1838 he helped found the Halifax Marine Insurance Association, and in the 1840s he was on the board of management of the Colonial Life Assurance Company. He was also a director of the Halifax Gas, Light, and Water Company, incorporated in 1840, and in 1844 helped incorporate the Halifax Water Company, becoming a director in 1856. By 1864 Keith was a director of the Provincial Permanent Building and Investment Society. At the time of his death his estate was evaluated at $251,000.

Keith’s interest in utilities and insurance was but part of his general involvement in the public life of Halifax. He was unsuccessful in the general election of 1840 when he stood as a Conservative candidate for the town of Halifax but was elected to the first city council in 1841. In 1842 he served as a commissioner of public property and in 1843 was selected mayor of Halifax. He continued as a member of council until he again served as mayor, by election, in 1853 and 1854. In December 1843 he was appointed to the Legislative Council and in June 1867 he accepted the appointment of president of the council, declining a seat in the Canadian Senate. As a supporter of confederation and president of the council, he was helped at first by the fact that before 1 July 1867 Charles Tupper* had filled several seats in the upper house with known confederates. Although the premier, William Annand*, appointed to the upper house in November 1867, had complete control of the lower house, he did not dare introduce a resolution into the upper chamber in 1868 calling for repeal of union. The anti-confederates gradually secured control of the upper house, however, and Keith was unable to prevent passage, in 1871, of a particularly flagrant bill which took the vote from all federal officials in provincial elections. It was perhaps a commentary on Keith that he was not actively involved at this time with the Conservative party organization which was run by such party stalwarts as Philip C. Hill* and James MacDonald*.

Throughout his career Keith was connected with several charitable and fraternal societies. He served as president of the North British Society from 1831 and as chief of the Highland Society from 1868 until his death. In 1838 he was connected with the Halifax Mechanics Library and in the early 1840s with the Nova Scotia Auxiliary Colonial Society. Keith was perhaps best known to the Halifax public as a leader of the freemasons. He became provincial grand master for the Maritimes under the English authority in 1840 and under the Scottish lodge in 1845. Following a reorganization of the various divisions in 1869, he became grand master of Nova Scotia.

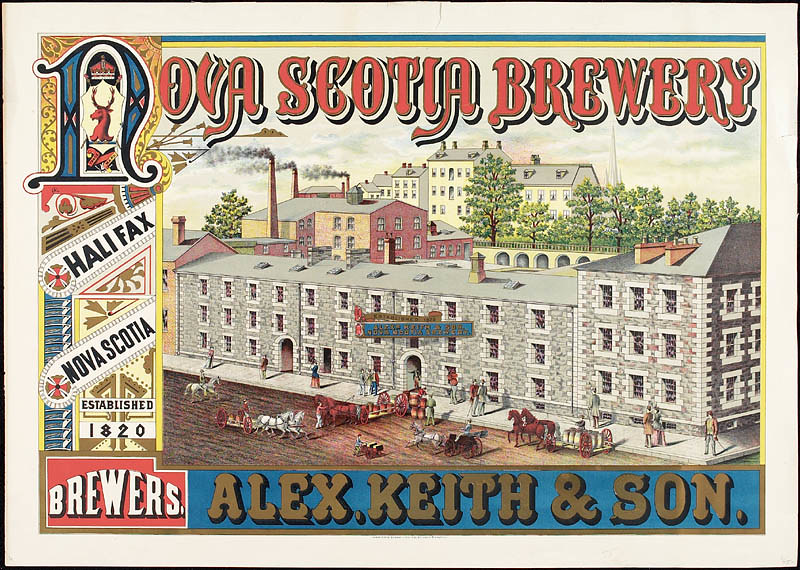

This short history of Keith’s brewery is from their Wikipedia page:

Founded in 1820, Alexander Keith’s is a brewery in Halifax, Canada. It is among the oldest commercial breweries in North America. (The oldest surviving brewing enterprise in Canada was established by John Molson in Montreal in 1786 while the oldest in the US, Yuengling, originally called Eagle Brewing, was founded in 1829 in Pottsville, PA.)

Keith’s was founded by Alexander Keith who emigrated from Scotland in 1817. Keith moved the facility to its final location, a three-storey building on Hollis Street at Lower Water in the downtown area, in 1820. Keith had trained as a brewer in Edinburgh and London. His early product included ale, porter, ginger wine, table and spruce beers. Alexander Keith was mayor in 1843 and in 1853-54 and president of the Legislative Council from 1867 to his death in 1873.

Keith’s was sold to Oland Breweries in 1928 and to Labatt in 1971. Today, the brewery is under the control of this subsidiary of Anheuser–Busch InBev which took the brand national in 1990’s. Keith’s also produces Oland Brewery beers, distributed in Eastern Canada.

In April 2011, Anheuser–Busch InBev began selling Alexander Keith’s beer in the United States after nearly two centuries of being available only in Canada.

AB InBev produces Keith’s India Pale Ale, currently the most popular product in this line,[6] as well as Keith’s Red Amber Ale, Keith’s Premium White, and Keith’s Light Ale.[7] Products sold in the United States are labelled Keith’s Nova Scotia Style Pale Ale, Keith’s Nova Scotia Style Lager, and Keith’s Nova Scotia Style Brown Ale.[8] Seasonal products have included Keith’s Ambrosia Blonde, Keith’s Harvest Ale, and Keith’s Tartan Ale. Although Alexander Keith products were originally produced in the Halifax brewery only for sale in the Maritimes, they are now national products, mass produced at AB InBev plants across Canada and in Baldwinsville, New York.