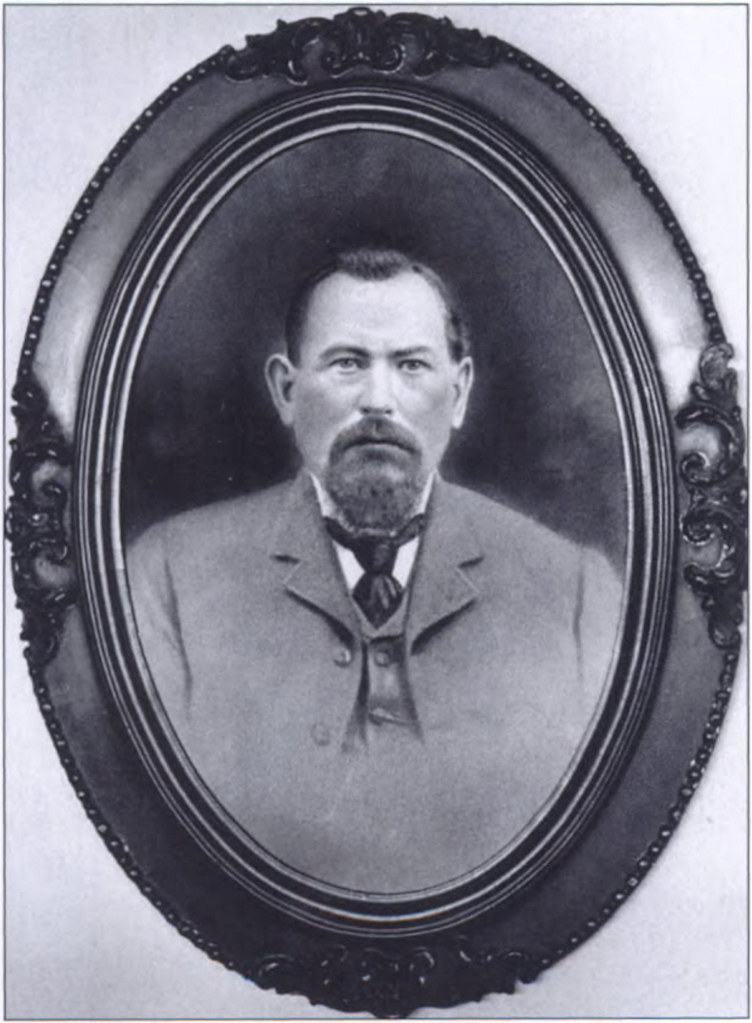

Today is the birthday of Peter P. Straub (June 28, 1850-December 17, 1913). He was born in Felldorf Starzach, Baden-Württemberg, Germany, and founded the Straub Brewery in St. Mary’s, Pennsylvania in 1872. The brewery is still owned and operated today by the Straub family.

Here’s his biography from his Wikipedia page:

Born to Anton Straub and his wife, Anna Maria Eger. The Straub family had been brewing a local beer for generations. As expected Peter learned a trade important to the brewing art. He became a Cooper, a craftsman who makes wooden barrels. Peter aspired to be a brewer and at the age of 19 in 1869 immigrated to the United States for a better and more prosperous life. Upon his arrival in the United States he found employment at the Eberhardt and Ober Brewing Company in Pennsylvania. Peter admired his employers’ pledge to forfeit $1,000 if any adulteration was found in their beer, and as he honed his brewing skills to a sharp edge, he adhered faithfully to this promise. Eventually he tired of city life and moved north to Brookville, where he perfected his brewing process while working in the Christ and Algeir Brewery.

Peter later moved to Benzinger (St. Marys), where he met and married Sabina Sorg of Benzinger. The couple settled in Benzinger and had ten children: Francis X., Joseph A., Anthony A., Anna M., Jacob M., Peter M. (who died at two years of age), Peter P., Gerald B., Mary C., and Alphons J.

Peter’s employment in Benzinger was with the Joseph Windfelder Brewery and he worked there until he purchased the Benzinger Spring Brewery (founded by Captain Charles C. Volk in 1855) from his father-in-law, Francis Xavier Sorg. It was then that Straub Beer and the Straub Brewery was born.

This early account of Straub’s life is from the brewery website:

Peter Straub was born on June 28, 1850 in Felldorf, Wuerttemburg, Germany, to Anton and Anna M. Eger Straub.

As a teenager, Peter was educated and worked as a cooper, which is a craftsman skilled in making and repairing wooden barrels and casks. He also became well versed in the allied trade of Brewing.

Peter honed his trade in Germany, France and Switzerland. At age 19 (in 1869), Peter Straub traveled to the United States and settled in Allegheny City, Pennsylvania, working at the Eberhardt and Ober Brewing Company. He next moved to Brookville and worked at the Christ and Allegeier Brewery. He again moved to Allegheny City and then to McKeesport and Centerville (later renamed Kersey). In 1872, Peter settled in St. Marys.

In St. Marys, Peter first worked at the Windfelder Brewery, which later became the Luhr Brewery, on Center Street. In the early 1870s, Peter was hired by Francis Sorg as brewmaster and manager for his brewery. The standard Straub Brewery founding date of 1872 reflects when Peter first moved to St. Marys and began brewing. He did not own the brewery until 1878.

Peter Straub began courting Francis Sorg’s eldest daughter, Sabina, marrying her on November 23, 1875. A few years later, Peter and Sabina, along with their eldest son Francis (one year old at the time) traveled back to Germany and then on to France, where they attended the Exposition Universelle in Paris. Peter and Sabina had 10 children: Gerard Benedict (Gerry), Peter (Sr.), Mary Crescentia (Marian, later Mrs. Daniel Curran), Alfonse James (Ponce), Peter Paul (Pete), Jacob Melchior (Fr. Gilbert), Joseph Anthony (Joe), Anna Angela (later Mrs. Frederick Luhr), Francis Xavier (Frank), Anthony Albert (Tony) and Peter Mathaeus (died at age two).

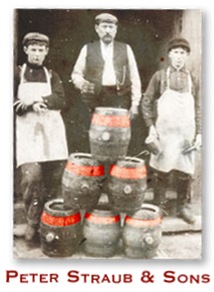

Straub Beer HistoryEarly on, Peter introduced his sons to the world of brewing. Straub used wooden kegs for his beer. He always placed a red band around his barrels to ensure that people would know they were drinking his beer and so that he would get them back. As a lasting trademark tribute to Peter, the brewery continues to place a bright red band around each of its barrels. Red has become a trademark color for the brewery.

Following Peter’s death on December 17, 1913, his sons assumed control of the brewery, renaming it the Peter Straub Sons Brewery. During this time, the brewery produced Straub Beer as well as other beer, such as the pilsner-style Straub Fine Beer and Straub Bock Beer. In 1920, the Straub Brothers Brewery purchased one half of the St. Marys Beverage Company, also called the St. Marys Brewery, where St. Marys Beer was produced. During Prohibition, which lasted from January 29, 1920, until December 5, 1933, the brewery produced nonalcoholic near-beer. On July 19, 1940 they purchased the remaining common stock and outstanding bonds of the St. Marys Beverage Company.

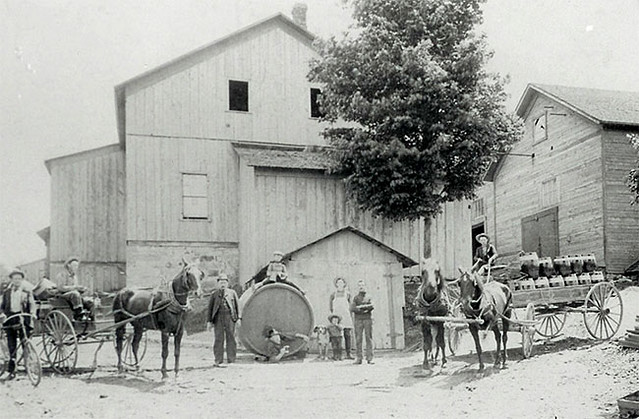

The Benzinger Spring Brewery in 1895.

And this account is by Erin L. Gavlock, from 2009, at the Pennsylvania Center for the Book at Penn State:

High in the Allegheny Mountains of Elk County, a tradition has been brewing for nearly a hundred and forty years. Straub (pronounced Strawb, not Strowb) Beer, the local brewery on Sorg Street in St. Marys, has not tampered with its recipe since Peter Straub crafted the lager’s signature taste in 1872. This sixth generation brewery is dedicated to preserving the original German formula and sticking in its original location, a difficult task for an old-time establishment in the modern era. For the descendents of Peter Straub, keeping the Straub custom is what makes the company a “brewery, not a beer factory.”

The tradition of Straub Beer began in the small village of Felldorf, Germany where Peter Straub was born into an lager-making family on June 28, 1850. He grew up in Germany learning the brewing business and eventually becoming a cooper, a maker of the wooden barrels used to hold beer. Like many other artisans of the time, Straub was unhappy with life as a cooper and dreamed of greater success. He wanted to participate in the family trade, to become a brewer of his own beer. Unable to rise above his economic status in Germany, Peter Straub took his vision and immigrated to the United States at the age of 19, arriving in Allegheny City, Pennsylvania in 1869.

In Allegheny City (now Pittsburgh’s north side), Straub went to work for Eberhardt and Ober, (the current Penn Brewery). At Eberhardt and Ober, Peter Straub became a student of his employer, John N. Straub (no relation) and quickly took to John’s administrative principles. The company promised to serve completely pure beer, untainted by additives such as salt or sugar, to its customers and backed that promise with a $1,000 refund to any contaminated sale. This code of law conduct rang true to Peter Straub and it became a principle he swore to brew by.

While perfecting his brewing technique in the city, Straub grew homesick for his quaint, German village. He decided to escape the loud, crowded streets of Allegheny City and retreated to the quietude of Elk County. He settled in St. Marys, marrying Sabina Sorg and working for various local breweries until Sabina’s father, Francis Xavier Sorg, sold his Benzinger Spring Brewery to him in 1872. Peter Straub finally got his long-awaited start as a brewer. Straub owned and operated the Benzinger Spring Brewery until he died in 1912 and left the company to his son, Anthony. Anthony Straub changed the name of the brewery to “Peter Straub Sons’ Brewery,” the only alteration he would make to his father’s business. From there, Peter Straub’s beer would become a Pennsylvania legend.

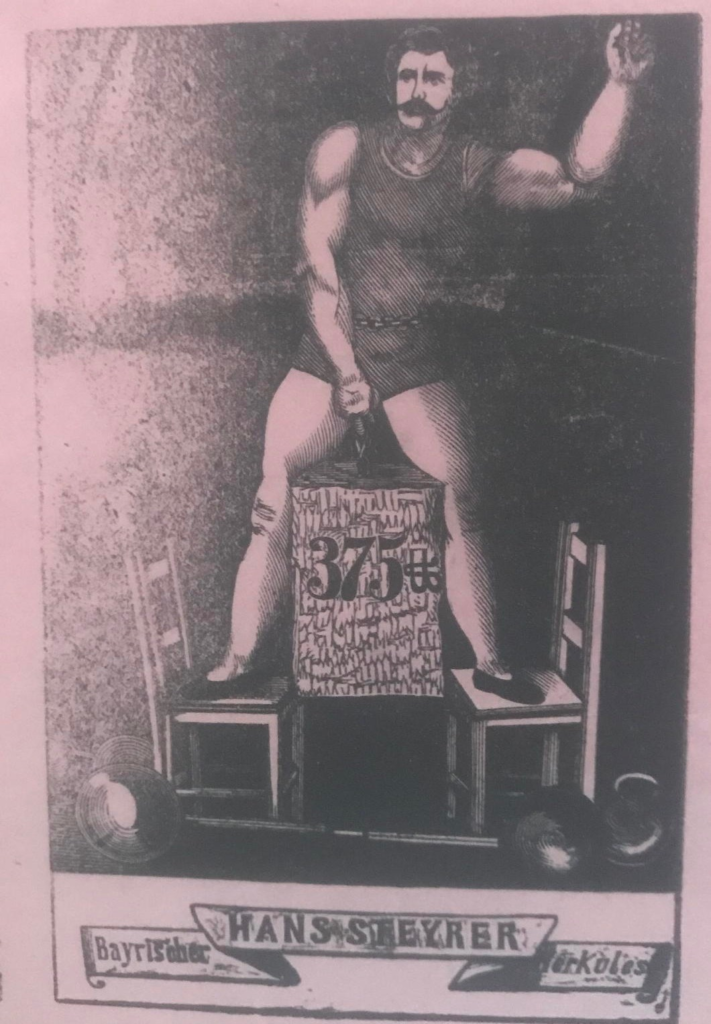

The Bavarian Man, a long-time image of the Straub Brewery that recalls its German roots.

Fast-forward over a hundred years from Straub’s humble beginnings to today and one will find the Straub Brewing pledge remains unchanged. The company still serves only unadulterated beer to its customers, proclaiming to be “The Natural Choice.” “Our all grain beer is brewed from Pennsylvania Mountain Spring water and we don’t add any sugar, salt, or preservatives to our recipes,” brew master Tom Straub told St. Marys’ Daily Press. “You can say our beer is a fresher, healthier choice than many of the selections in the marketplace.” Although time and technology have forced a transformation in brewing techniques and standards, the taste, ingredients, and the location of Straub have remained constant. Still located in St. Marys, the brewery depends upon the same mountain water from the Laurel Run Reservoir to blend with all-natural ingredients of cornflakes (used to produce fermentable sugars), barley and hops. “Our brewing process is virtually unchanged since our great, great, grandfather, Peter Straub, perfected it in 1872,” Straub’s promises. The reason behind sticking to the fresh taste of the original recipe is simple: people like it. Through the century, Straub has grown a dedicated patronage in western Pennsylvania with its traditional flavor. “Our style of brewing has pretty much stayed the same over the years, but what is interesting is that our popularity has grown and the reputation of our hand-crafted beer has increased,” Straub CEO Bill Brock said. “It is nice to know that we are becoming increasingly popular not for something we’ve changed, but rather for something we’ve always done well.”The choice to protect and maintain the brewing customs has kept Straub a small, family owned brewery. “We’ve always thought small. We’re more about quality than quantity,” Dan Straub, former CEO, told Fredericksburg, Virginia’s Free-Lance Star. Until June 2009, Straub Beer was only distributed in glass bottles throughout Pennsylvania and Ohio. Now Straub is being brewed and distributed in aluminum cans in Rochester, New York at the High Falls Brewery. The recipe and method have not changed in the new setting and are under the careful watch of brew master Tom Straub. Despite the recent company growth, Straub still only produces about 45,000 barrels of beer per year. “We are unique; we are much larger than a micro brewery yet far, far smaller than some of the leading national brands,” said Bill Brock. In the middle ground, the brewery has managed to survive beer tycoons, economic depression, and cultural trends—a tough maneuver for a company exporting from Pennsylvania’s least populated region. “I believe the brewery has survived because of the fact that it is family owned; it is steeped in tradition and we have an absolute passion for making beer and our products,” said Brock. “From my perspective, the company and our traditions are a huge legacy and there is a clear obligation to continue these traditions.” Keeping to the family legacy has allowed Straub to persevere through the years to become the second oldest brewery in Pennsylvania after Yuengling.

Staying small and faithful to the company’s founding principles has enabled Straub to keep traditions that other larger breweries have been forced to abandon. The returnable bottle, an eco-friendly service that allows customers to send glass bottles back to the brewery for recycling, is still offered at Straub. “We stayed with the returnable bottles first of all, and I think this is really important, because we have a really strong customer base and they like the returnables,” Bill Brock said during a 2009 radio broadcast. “Over the years we maintained it while other breweries slowly fazed them out.” For Straub, a successful regional brewery, shipping bottles back to the factory is feasible, where it would create more pollution for national brands to do the same. In the future, Straub hopes to go greener and offer more returnables to customers. “We’d love for it to grow,” Brock said. “We think it is the right thing to do and if we can blend the right thing to do with making our customers happy that’s almost a perfect world.”

Another Peter Straub tradition kept to make customers happy is the Eternal Tap, an oasis for Elk County beer drinkers. The Eternal Tap, established long before any of the brewery’s current chief operators were born, is a “thank you” gesture for patrons, daily providing two mugs of complimentary, fresh cold beer to anyone of legal drinking age. “The roots of it go as far back as the brewery itself and I am sure that my great, great, grandfather, his workers and their friends would spend time at the end of the week enjoying a few pints of freshly brewed beer,” Brock said. According to Bloomington, Illinois’ Pantagraph, the Eternal Tap sprang up shortly after Peter Straub received the Benzinger Spring Brewery from his father-in-law as a way to draw beer enthusiasts to the taste of Straub. Since the marketing gimmick started in 1872, the Eternal Tap has not been turned off, giving free beer to customers in good times and bad.

Although Straub has been in operation for more than a century since its founder’s death, if Peter Straub were able to return to his brewery today, he might feel as if he still ran it. The original recipe, the customer appreciation, and the environmental concerns he founded his business upon are still principal brewing laws at Straub today. For the descendents of Peter Straub, keeping the tradition was second nature. “For me, being President/CEO, my job is to be faithful to the traditions and it is really not that difficult,” Brock said. “I have one of the best jobs in the world and I have been given the opportunity to continue an important tradition and legacy.”

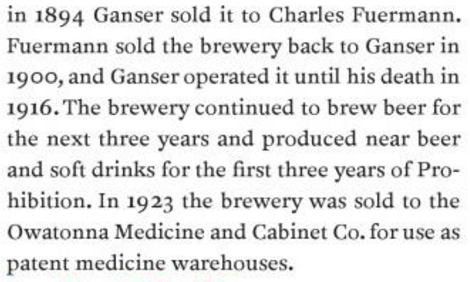

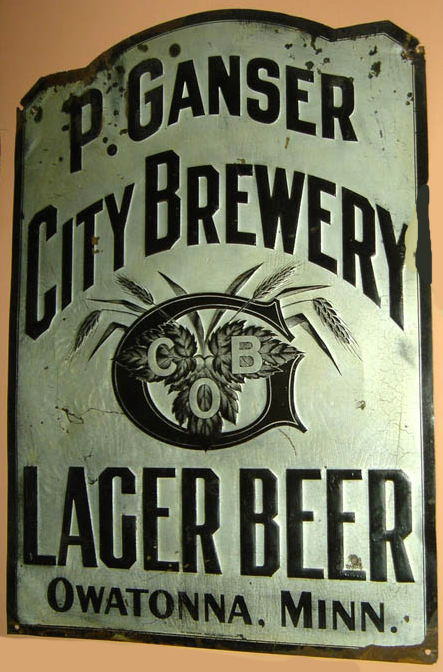

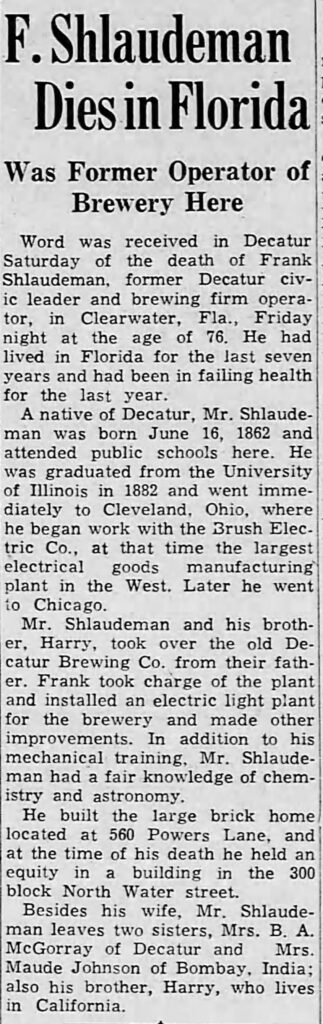

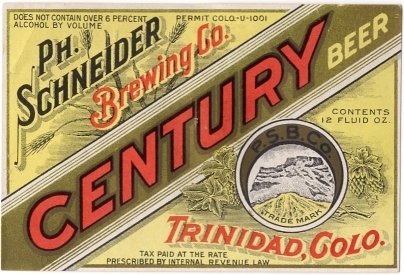

Ganser Brau Near Beer.

Ganser Brau Near Beer.