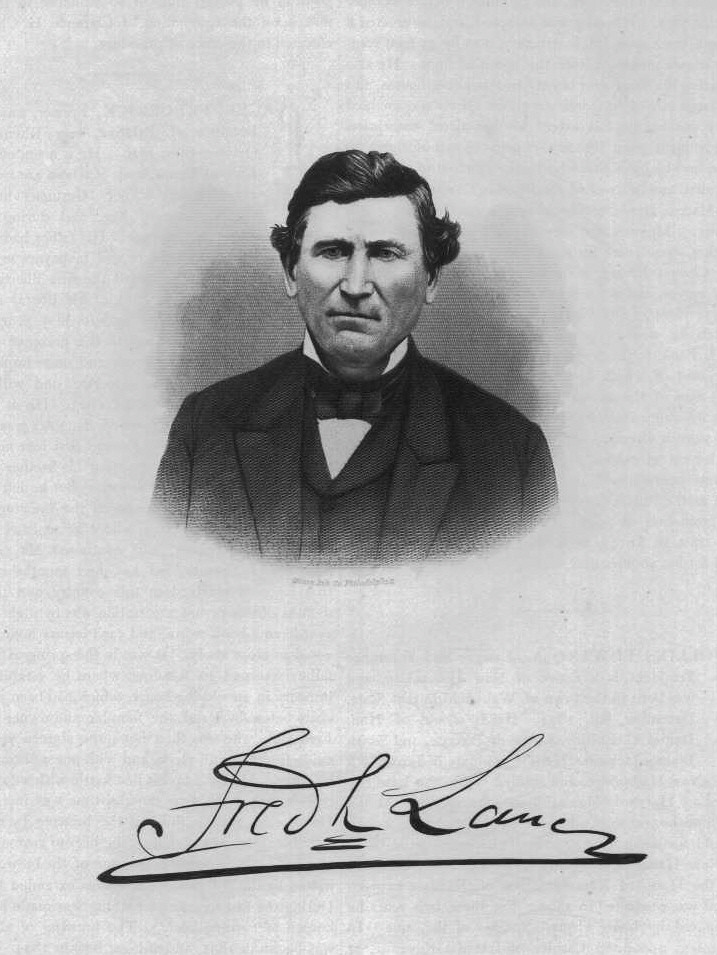

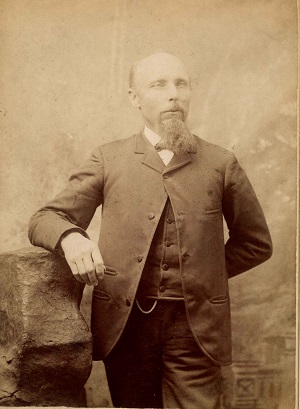

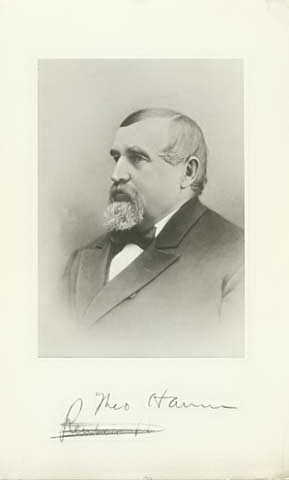

Today is the birthday of Theodore Hamm (October 14, 1825-July 31, 1903). He was born in Emmendingen, Emmendingener Landkreis, Baden-Württemberg, Germany. Hamm emigrated in 1856 with his wife Louise to the United States and settled in St. Paul. In the 1860s, Hamm assisted brewer Andrew F. Keller, so that he could expand his business. The brewery was taken as a security deposit. When the Keller brewery went bankrupt, it became the property of Hamm, and he founded the Hamm Brewing Company in 1865.

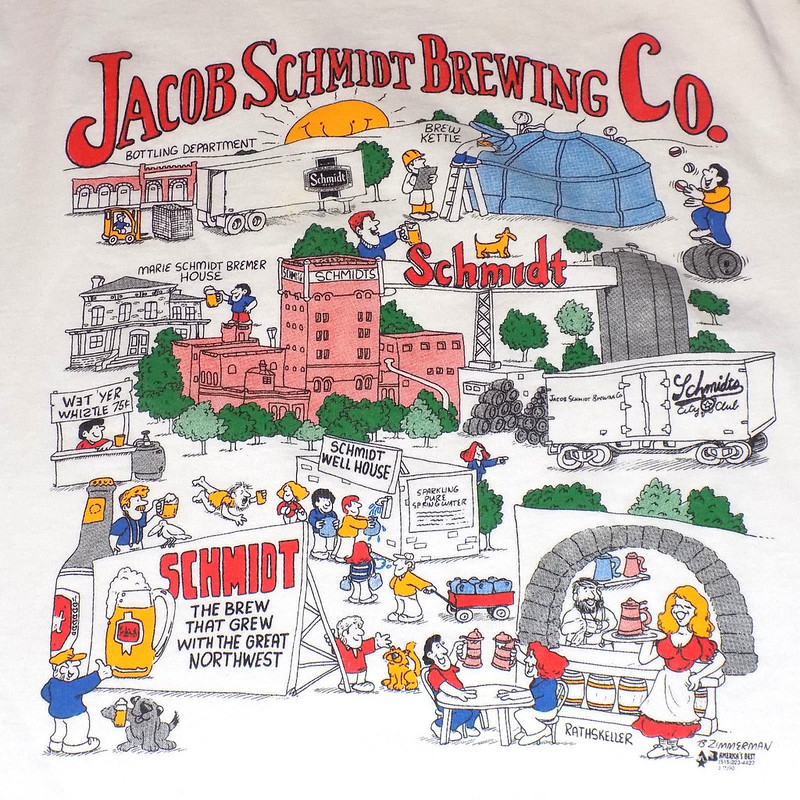

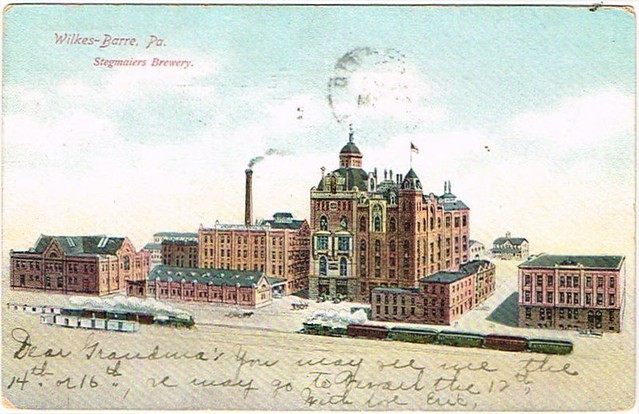

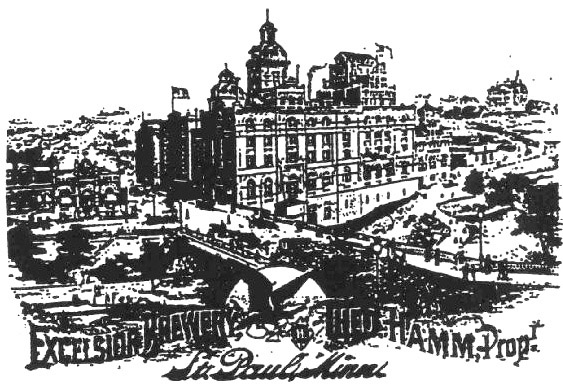

Theodore and Louise Hamm, a young German immigrant couple, found a home in St. Paul, Minnesota in 1856. In 1864, entrepreneur Andrew F. Keller, the owner of a small brewery called the Excelsior Brewery (then producing 500 barrels a year) needed money for expansion. Theodore lent the money with the brewery as collateral. When Keller defaulted on the loan, Theodore Hamm was the owner of a brewery. The size of the work force grew, as did the total number of barrels brewed. In 1865 there were 5 employees that brewed 500 barrels a year, which grew to 75 employees brewing 40,000 barrels a year in 1885. In 1894 the brewery expanded to include a bottling works, followed by artificial refrigeration in 1895. In 1894 an open house was held and free samples of beer were handed out, beginning the long tradition of brewery tours. The brewery was incorporated in 1896, giving Theodore the title of president and William the titles of vice-president and secretary. The line to succession of the brewery was thus established, as the brewery remained in domain of the Hamm’s family for 100 years.

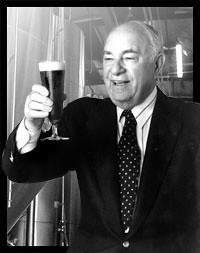

The brewery continued to expand from 8,000 barrels in 1879, to 26,000 barrels in 1882, to 600,000 barrels in 1915. This growth was stymied from 1919-1933 during prohibition. During prohibition, the plant was kept open and an array of products including near beer, industrial alcohol syrups and soft drinks were produced. Soon after the death of his father, William Hamm Jr. started the greatest expansion effort in the tenure of the brewery. The capacity was doubled and the plant was modernized. EC Nippolt, vice president and general manager of the company, estimated that an increase of at least double the number of employees from 150 to 300 or 400. An estimate from newspaper accounts reveals an expenditure of $300,000 in immediate improvements to be made to the plant.

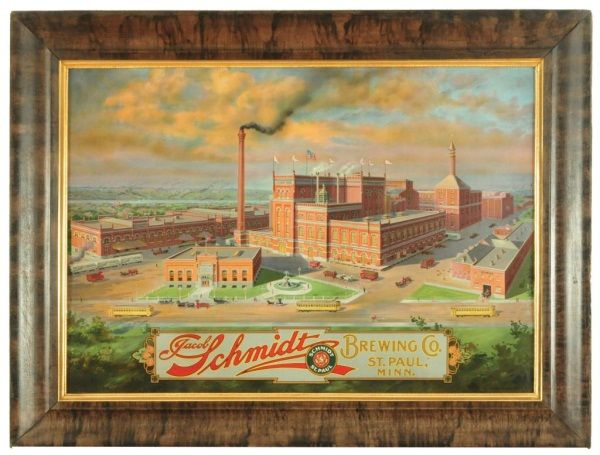

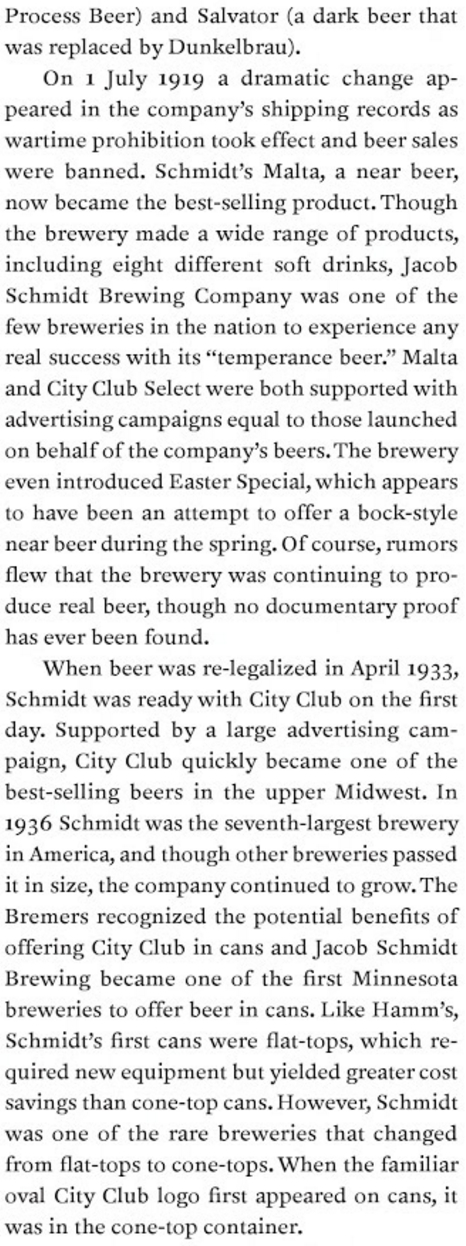

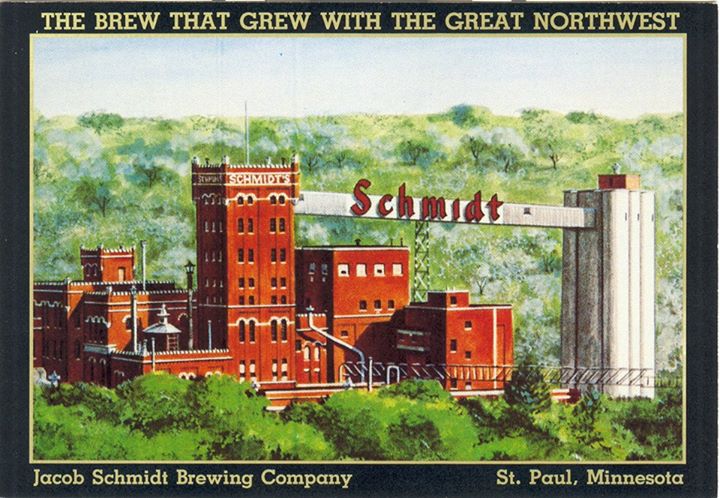

The Theodore Hamm Brewing Company was established in 1865 when, a German immigrant Theodore Hamm (1825-1903) inherited the Excelsior Brewery from his friend and business associate A. F. Keller, who had perished in California seeking his fortune in the gold fields. Unable to finance the venture himself, Keller had entered into a partnership with Hamm to secure funding. Upon Keller’s death, Hamm inherited the small brewery and flour mill in the east side wilderness of St. Paul, Minnesota. Keller had constructed his brewery in 1860 over artesian wells in a section of the Phalen Creek valley in St. Paul known as Swede Hollow. Hamm, a butcher by trade and local salon owner, first hired Jacob Schmidt as a brew master. Jacob Schmidt remained with the company until the early 1880s, becoming a close family friend of the Hamms. Jacob Schmidt left the company after an argument ensued over Louise Hamm’s disciplinary actions to Schmidt’s daughter, Marie. By 1884, Schmidt was a partner at the North Star Brewery not far from Hamm’s brewery. By 1899 he had established his own brewery on the site of the former Stalhmann Brewery site. In need of a new brewmaster, Hamm hired Christopher Figge who would start a tradition of three generations of Hamm’s Brewmasters, with his son William and grandson William II taking the position. By the 1880s, the Theodore Hamm Brewing Company was reportedly the second largest in Minnesota.

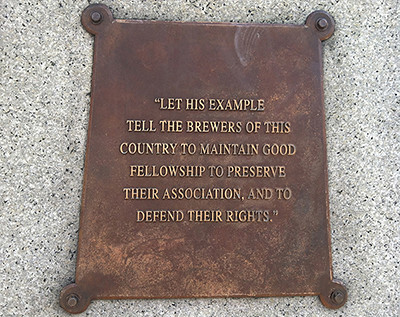

Theodore’s obituary was published in the American Brewer’s Review:

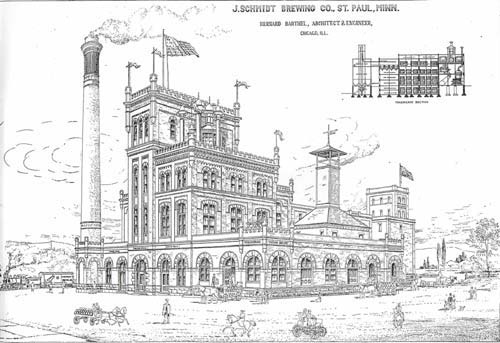

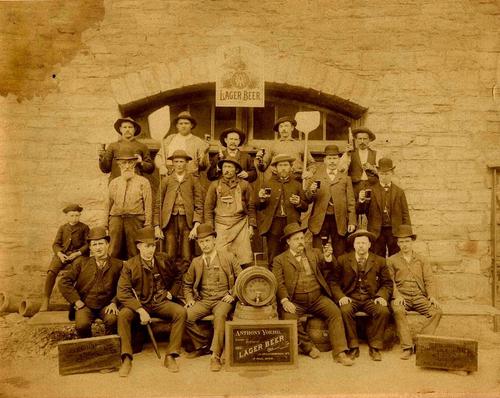

Hamm’s Brewery c. 1900.