Today is the birthday of Frederick C. Miller (February 26, 1906–December 17, 1954). Fred was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, “the son of Carl A. Miller of Germany, and Clara Miller (no relation), a daughter of Miller Brewing Company founder Frederick Miller.

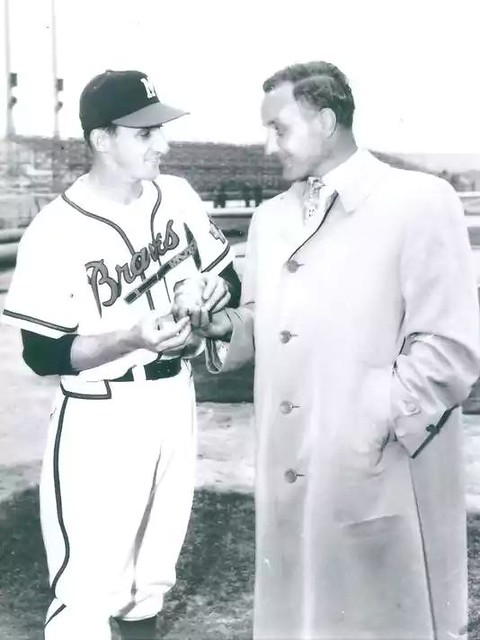

Succeeding his younger cousin Harry John (1919–1992), Miller became the president of the family brewing company in 1947 at age 41 and had a major role in bringing Major League Baseball to Wisconsin, moving the Braves from Boston to Milwaukee in 1953. He coaxed Lou Perini into moving them into the new County Stadium and the Braves later played in consecutive World Series in 1957 and 1958, both against the New York Yankees. Both series went the full seven games with Milwaukee winning the former and New York the latter.

Fred Miller was also notably a college football player, an All-American tackle under head coach Knute Rockne at the University of Notre Dame, posthumously elected to the College Football Hall of Fame in 1985. He later served as an unpaid assistant coach for the Irish, flying in from Milwaukee several times a week.

He also “volunteered as a coach for the Green Bay Packers and, during a difficult financial period, even helped fund the team. Miller Brewing remains the largest stockholder of the Green Bay Packers,” which probably explains why they played half of their home games in Milwaukee before Lambeau Field was refurbished.

Here’s his biography from the College Football Hall of Fame:

A native of Milwaukee, Fred Miller was the grandson of the founder of the Miller Brewing Company. The qualities which later made Fred a great business executive were already evident when he entered Notre Dame in 1925, and they were quickly recognized by the immortal Knute Rockne. It was under Rockne’s tutelage that the 6-1, 195-pounder came to his gridiron peak, earning All-America mention in 1927, and again in 1928, and achieving the ultimate Notre Dame football honor by being named captain of the 1928 team. His quest for perfection was not limited to the gridiron. During his years at Notre Dame he coupled athletic prowess with academic proficiency and established the highest scholastic average of any monogram winner. Miller was involved in real estate, lumber, and investments before becoming president of the Miller Brewing Company. In 1954, he and his son, Fred Jr., were killed in an airplane crash. Miller was 48 years old. He was survived by his wife, six daughters and a son.

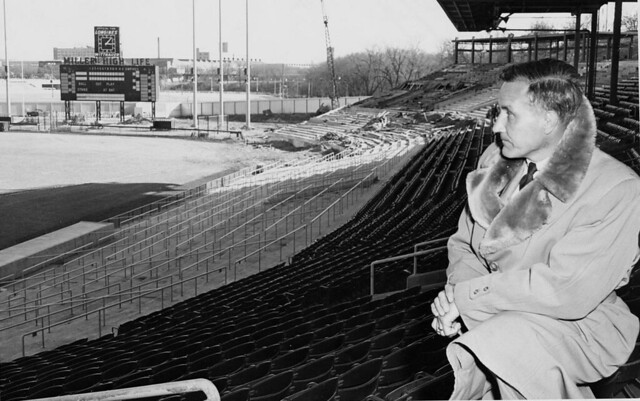

Miller at Milwaukee’s County stadium, where he helped moved the Boston Braves to in 1953, along with paying $75,000 for the County Stadium scoreboard in the background.

But beyond his sports accomplishments, he was an effective leader of his family’s brewery, as detailed by the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel in Remembering Frederick C. Miller, Milwaukee brewing’s 1st rock star:

Frederick C. Miller was the first brewery rock star.

Industry types praised Miller in the 1940s and early ’50s in the same way they gush over leading craft brewers today.

Frederick J. Miller was the builder of the brewery that is marking its 160th anniversary this year. Frederick’s son, Ernest, who took over after his father’s death, was a caretaker for the brewery keeping the status quo.

But Frederick C. Miller, part of the focus of a monthlong celebration of the company’s history that wrapped up last weekend, was the innovator who sparked new relationships, new buildings, put new ideas in motion and marched the family brewery past regional dominance to become the nation’s fifth-ranked brewery.

When you sip a beer at Miller Park or Lambeau Field it’s because of Fred C. He identified the relationship between beer and sports, and ran with it like the all-American football player he was.

“Fred was iconic,” said David S. Ryder, MillerCoors vice president for brewing, research, innovation and quality. “He was named as president of Miller Brewing in 1947, and from the day that he was named president, Miller Brewing started to grow.”

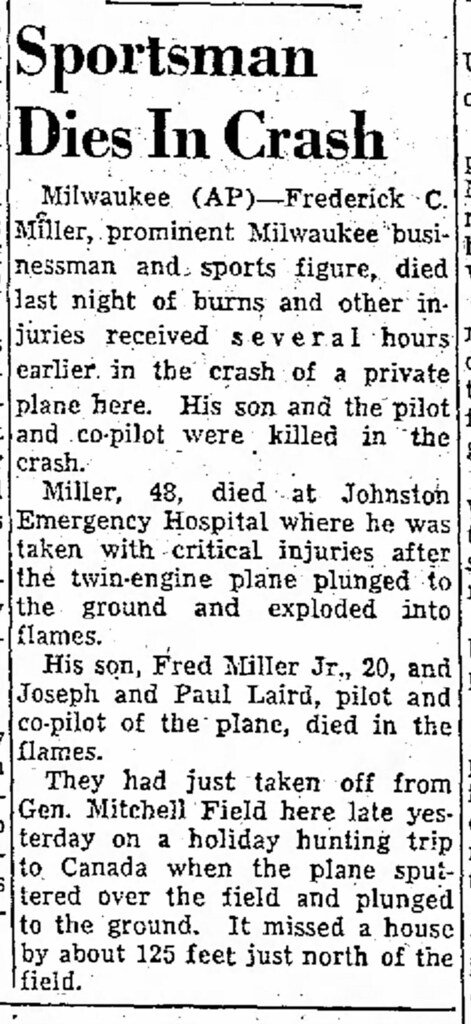

Frederick C. died when his plane crashed on takeoff at what is now Mitchell International Airport on Dec. 17, 1954. He was 48. His son Fred Jr., 20, and two pilots on the Miller Brewing payroll were killed on impact in the crash; Frederick C. was thrown clear of the crash but died hours later in the hospital.

A crowd of 3,000 mourners attended the funeral services, and the overflow was described by The Milwaukee Journal as “everyday folks — men in overalls and other rough work clothes, mothers carrying babies, young people and old.”

During Frederick C.’s time, Miller’s brewery expanded and sales grew from 653,000 barrels in 1947 to more than 3 million in 1952. He added buildings, including a new brewhouse and a new office building. He turned the former ice caves into The Caves Museum, a place where brewers could assemble for lunch or special occasions.

Liberace, a West Allis native, cut the ribbon for The Caves in 1953, according to John Gurda’s book “Miller Time: A History of Miller Brewing Company.”

Here’s a newspaper account of the tragic death of Fred and his son in 1954.

And lastly, here’s some interesting speculation from my friend, historian Maureen Ogle, that Miller Brewing might have done considerably better against their rival, Anheuser-Busch, if Fred Miller had not died prematurely in that place crash when he was only 48 years old.

It’s rare that the presence or absence of one person makes a historical difference (I said “rare,” not impossible). But I think that the death of Fred C. Miller in 1954 altered the course of American brewing. Miller was aggressive, ambitious, smart — all on a grand scale. He was the first beermaker to come along in decades who showed the potential to go head-to-head with the Busch family, particularly Gus Busch, who ran A-B from the late 1940s until the mid-1970s.

Miller became company president in 1947, and over the next few years, he shoved, pushed, prodded, and otherwise steered his family’s brewing company not-much-of-anything into the ranks of the top ten. But in late 1954, he died (in a plane crash) — and Miller Brewing lost its way.

As Miller faltered, A-B solidified its position as the dominant player in American brewing. Had Fred Miller not died, I believe the course of American brewing would have turned out differently: Fred Miller would have transformed his family’s company into a formidable powerhouse. He would have challenged A-B’s dominance. He would have been able to command-and-direct in a way that, for example, Bob Uihlein was not able to do at Schlitz during the same period.

Put another way, in the 1950s, Gus Busch met his match in Fred C. Miller. Things might have turned out differently had Miller lived

I can’t prove that, of course, but hey — what’s all that research good for if I can’t express an informed opinion.

And lastly, the Wisconsin Business Hall of Fame created a short video of Miller’s life that’s a nice over view of him.