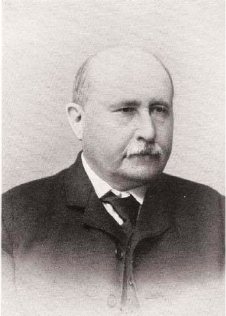

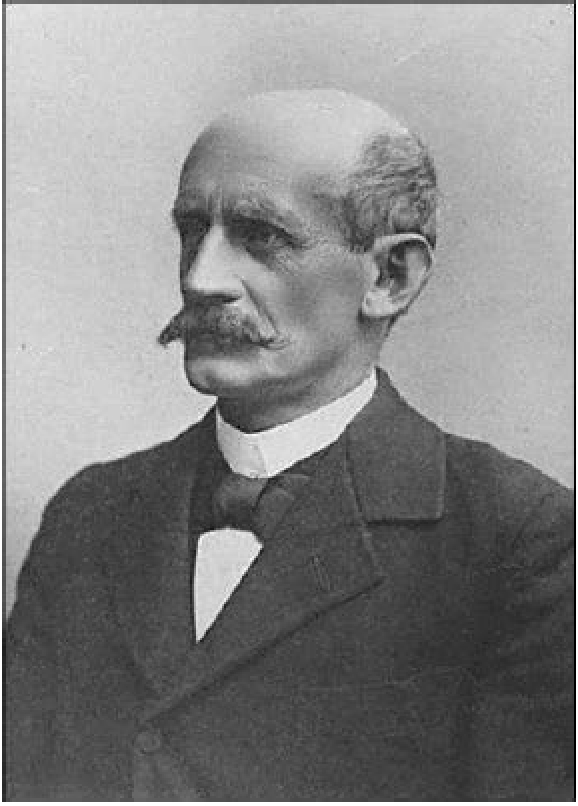

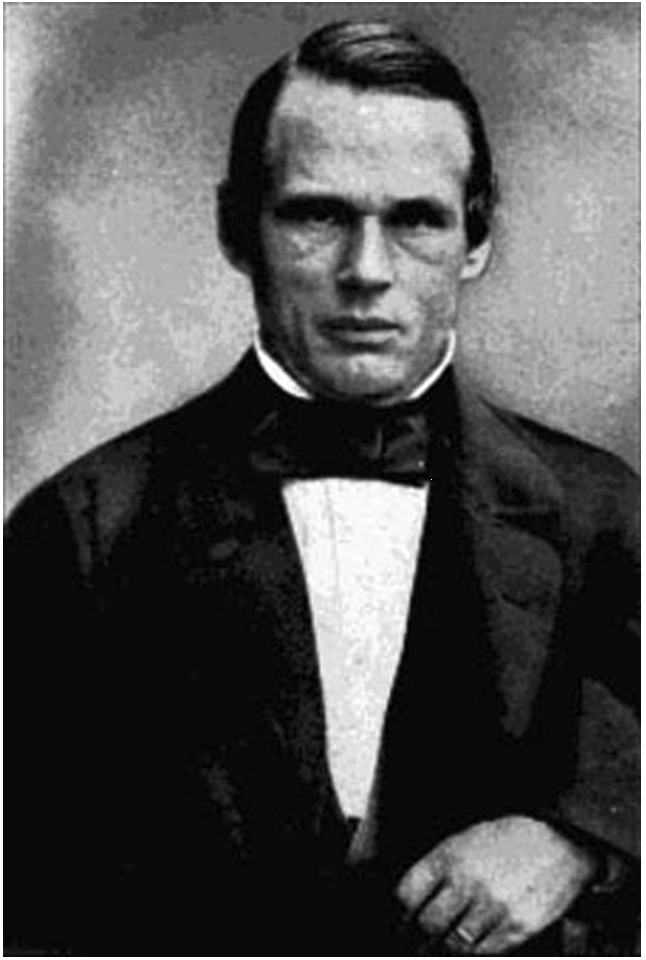

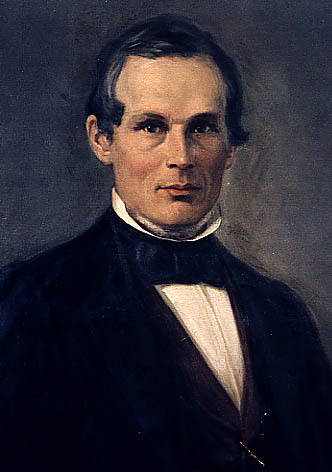

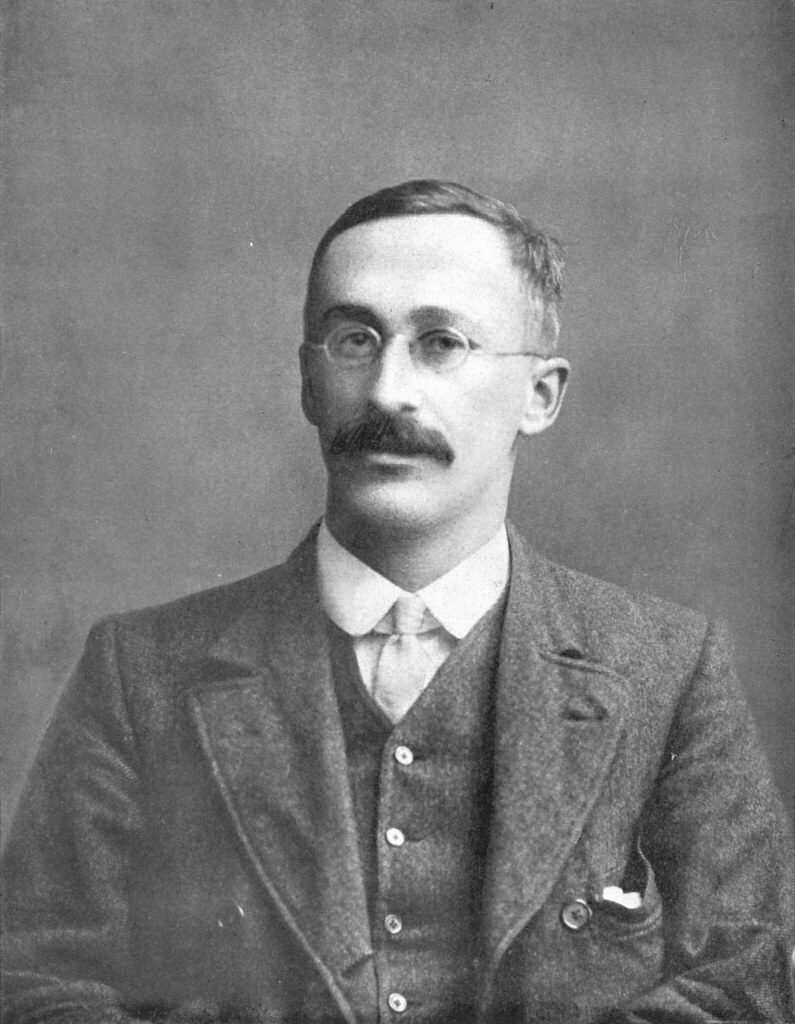

Today is the birthday of John Ewald Siebel (September 17, 1868-December 20, 1919). Siebel was born in Germany, but relocated to Chicago, Illinois as a young man. Trained as a chemist, in 1868 he founded the Zymotechnic Institute, which was later renamed the Siebel Institute of Technology.

Here’s his obituary from the Foreign Language Press Survey:

Professor John Ewald Siebel has died after an active life devoted to science. Besides his relatives, thousands of his admirers, including many men of science, mourn at the bier of the friendly old man. He died in his home at 960 Montana Avenue.

Professor Siebel was born September 18, 1845, in Hofkamp, administrative district of Dusseldorf [Germany], as the son of Peter and Lisette Siebel; he attended high school [Real-Gymnasium] at Hagen and studied chemistry at the Berlin University. He came to the United States in 1865 and shortly afterwards obtained employment as a chemist with the Belcher Sugar Refining Company in Chicago. Already in 1868, he established a laboratory of his own, and from 1869 until 1873 he was employed as official chemist for the city and county. In 1871 he also taught chemistry and physics at the German High School. From 1873 until 1880 he was official gas inspector and city chemist. During the following six years he edited the American Chemical Review, and from 1890 until 1900 he published the Original Communications of Zymotechnic Institute. He was also in charge of the Zymotechnic Institute, which he had founded in 1901. Until two years ago he belonged to its board of directors.

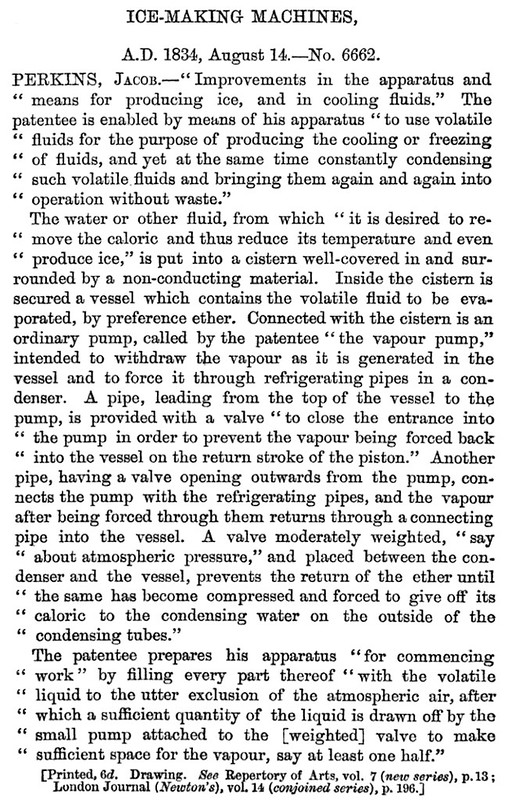

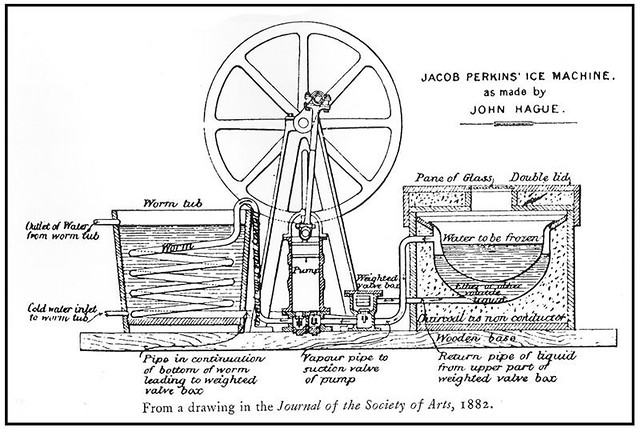

Among the many scientific works published by the deceased, which frequently won international reputation, and are highly valued by the entire world of chemical science are: Newton’s Axiom Developed; Preparation of Dialized Iron; New Methods of Manufacture of Soda; New Methods of Manufacture of Phosphates; Compendium of Mechanical Refrigeration; Thermo-and Electro-Dynamics of Energy Conversion; etc. The distilling industry considered him an expert of foremost achievement.

The deceased was a member of the Lincoln Club; the old Germania Club; the local Academy of Science; the Brauer and Braumeisterverein [Brewer and Brewmaster Association]; the American Institute for Brewing; and the American Society of Brewing Technology. Professor Siebel was also well known in German circles outside the city and state.

His wife Regina, whom he married in 1870….died before him. Five sons mourn his death: Gustav, Friedrich, Ewald, Emil and Dr. John Ewald Siebel, Jr. Funeral services will be held tomorrow afternoon at Graceland Cemetery.

Professor Siebel was truly a martyr of science. He overworked himself, until a year ago he suffered a nervous breakdown. About four months ago conditions became worse. His was an easy and gentle death.

The Siebel Institute’s webpage tells their early history:

Dr. John Ewald Siebel founded the Zymotechnic Institute in 1868. He was born on September 17, 1845, near Wermelskirchen in the district of Dusseldorf, Germany. He studied physics and chemistry and earned his doctorate at the University of Berlin before moving to Chicago 1866. In 1868 he opened John E. Siebel’s Chemical Laboratory which soon developed into a research station and school for the brewing sciences.

In 1872, as the company moved into new facilities on Belden Avenue on the north side of Chicago, the name was changed to the Siebel Institute of Technology. During the next two decades, Dr. Siebel conducted extensive brewing research and wrote most of his over 200 books and scientific articles. He was also the editor of a number of technical publications including the scientific section of The Western Brewer, 100 Years of Brewing and Ice and Refrigeration.

In 1882 he started a scientific school for brewers with another progressive brewer but the partnership was short lived. Dr. Siebel did, however, continue brewing instruction at his laboratory. The business expanded in the 1890’s when two of Dr. Siebel’s sons joined the company.

The company was incorporated in 1901 and conducted brewing courses in both English and German. By 1907 there were five regular courses: a six-month Brewers’ Course, a two-month Post Graduate Course, a three-month Engineers’ Course, a two-month Maltsters’ Course and a two-month Bottlers’ Course. In 1910, the school’s name, Siebel Institute of Technology, was formally adopted. With the approach of prohibition, the Institute diversified and added courses in baking, refrigeration, engineering, milling, carbonated beverages and other related topics. On December 20, 1919, just twenty-seven days before prohibition became effective, Dr. J. E. Siebel passed away.

With the repeal of prohibition in 1933 the focus of the Institute returned to brewing under the leadership of F. P. Siebel Sr., the eldest son of Dr. J. E. Siebel. His sons, Fred and Ray, soon joined the business and worked to expand its scope. The Diploma Course in Brewing Technology was offered and all other non-brewing courses were soon eliminated. Then in October 1952, the Institute moved to its brand new, custom built facilities on Peterson Avenue where we have remained for almost 50 years.

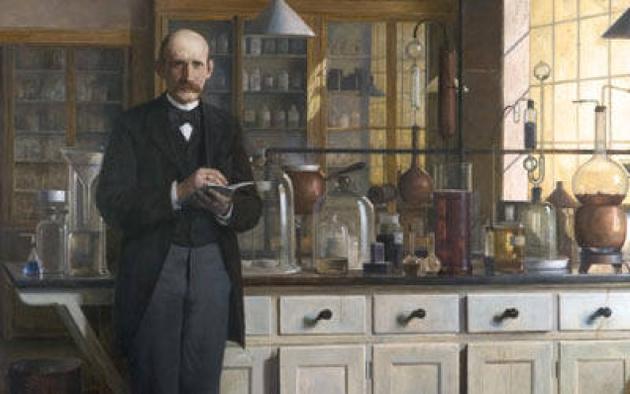

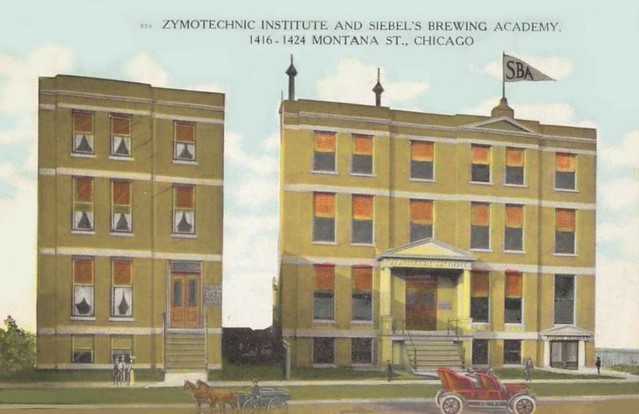

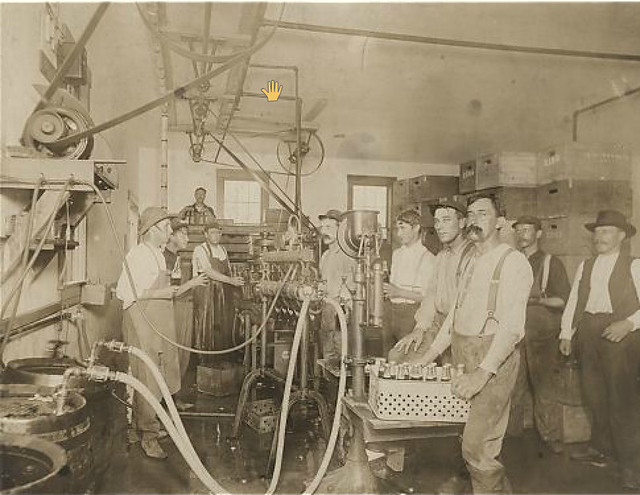

Siebel Brewers Academy c. 1902-04.

Here’s another short account from the journal Brewery History, in an article entitled “A History of Brewing Science in the United States of America,” by Charles W. Bamforth:

Dr John Ewald Siebel (1845-1919) was born on September 17th 1845 at Hofcamp, near Düsseldorf. Upon visiting an uncle in US after the completion of his doctorate in chemistry and physics he became chief chemist at Belcher’s sugar refinery in Chicago, aged 21, but that company soon folded. Siebel stayed in Chicago to start an analytical laboratory in 1868, which metamorphosed into the Zymotechnic Institute.

With Chicago brewer Michael Brand, Siebel started in 1882 the first Scientific School for practical brewers as a division of the Zymotechnic Institute. True life was not breathed into the initiative until 1901 with Siebel’s son (one of five) Fred P. Siebel as manager. This evolved to become the Siebel Institute of Technology, which was incorporated in 1901 and conducted brewing courses in both English and German. Within 6 years five regular courses had been developed: a six-month course for brewers, a twomonth post graduate course, a threemonth course for engineers, a two-month malting course and a two-month bottling course.

Amongst Siebel’s principal contributions were work on a counter pressure racker and artificial refrigeration systems. Altogether he published more than 200 articles on brewing, notably in the Western Brewer and original Communications of the Zymotechnic Institute. Brewing wasn’t his sole focus, for instance he did significant work on blood chemistry.

Son EA Siebel founded Siebel and Co and the Bureau of Bio-technology in 1917, the year that prohibition arrived. Emil Siebel focused then on a ‘temperance beer’ that he had been working on for nine years. Courses in baking, refrigeration, engineering, milling and nonalcoholic carbonated beverages were offered.