![]()

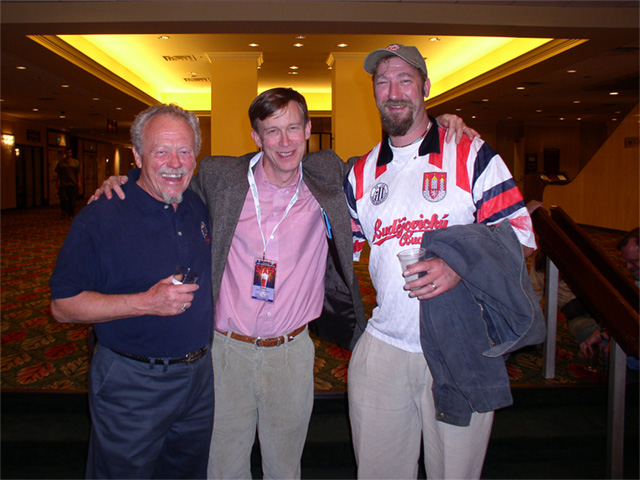

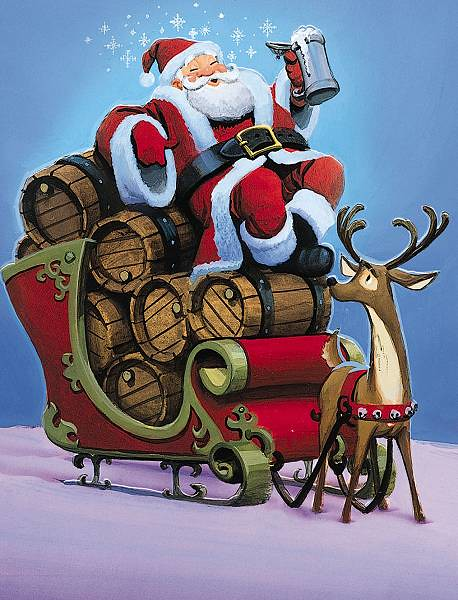

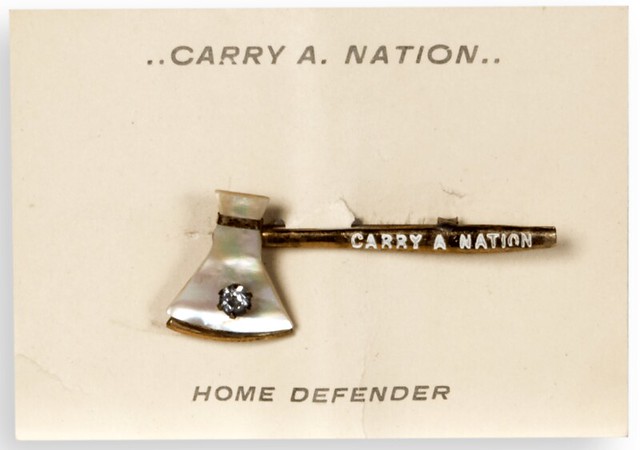

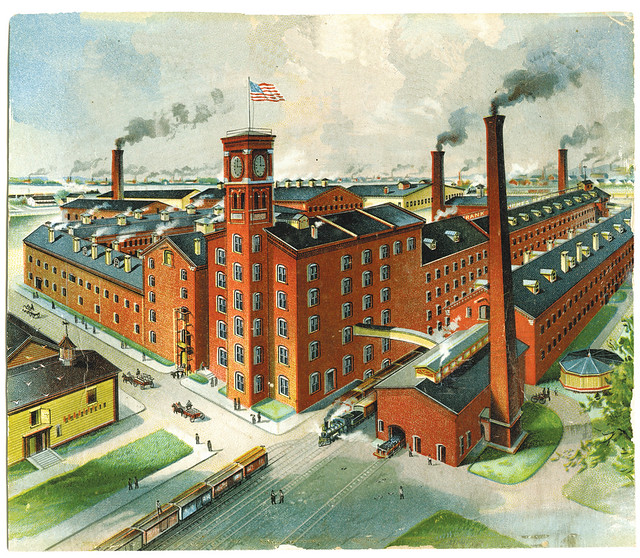

Today is the 74th birthday of Senator — and former Colorado Governor and Denver mayor — John Hickenlooper. John was also the co-founder of Wynkoop Brewery in Denver’s LoDo District, and in fact is credited with helping to revitalize the whole area. After being a popular, and by all accounts very effective mayor, for several years, he was elected as the Governor of Colorado, and more recently Senator for Colorado. John’s been great for Denver, Colorado and craft brewing. Join me in wishing John a very happy birthday.