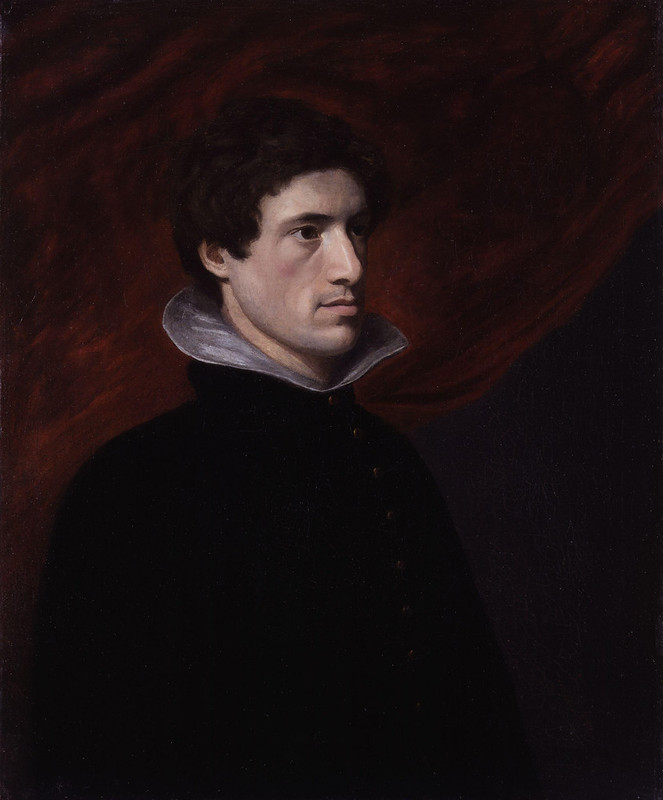

Christopher Smart was an English poet (April 11, 1722–May 21, 1771). He “was a major contributor to two popular magazines and a friend to influential cultural icons like Samuel Johnson and Henry Fielding. Smart, a high church Anglican, was widely known throughout London.” He had some goofy nicknames, such as “Kit Smart”, “Kitty Smart”, and “Jack Smart.”

Here’s some basic info about him from Wikipedia:

Smart was infamous as the pseudonymous midwife “Mrs. Mary Midnight” and widespread accounts of his father-in-law, John Newbery, locking him away in a mental asylum for many years over Smart’s supposed religious “mania”. Even after Smart’s eventual release, a negative reputation continued to pursue him as he was known for incurring more debt than he could repay; this ultimately led to his confinement in debtors’ prison until his death.

Smart’s two most widely known works are A Song to David and Jubilate Agno, both at least partly written during his confinement in asylum. However, Jubilate Agno was not published until 1939 and A Song to David received mixed reviews until the 19th century. To his contemporaries, Smart was known mainly for his many contributions in the journals The Midwife and The Student, along with his famous Seaton Prize poems and his mock epic The Hilliad. Although he is primarily recognised as a religious poet, his poetry includes various other themes, such as his theories on nature and his promotion of English nationalism.

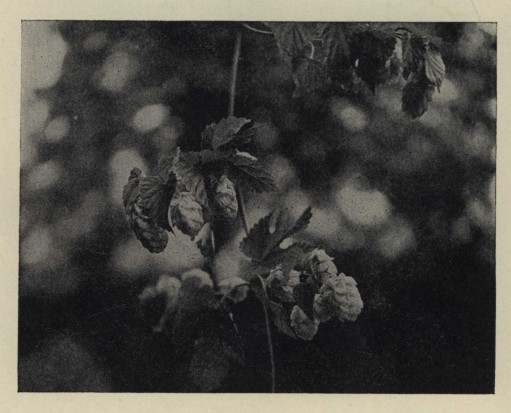

One of his longer poems was called “The Hop-Garden” and was first published in 1752. It was originally part of Poems on Several Occasions, an early collection of Smart’s poems. Here’s how Wikipedia describes it:

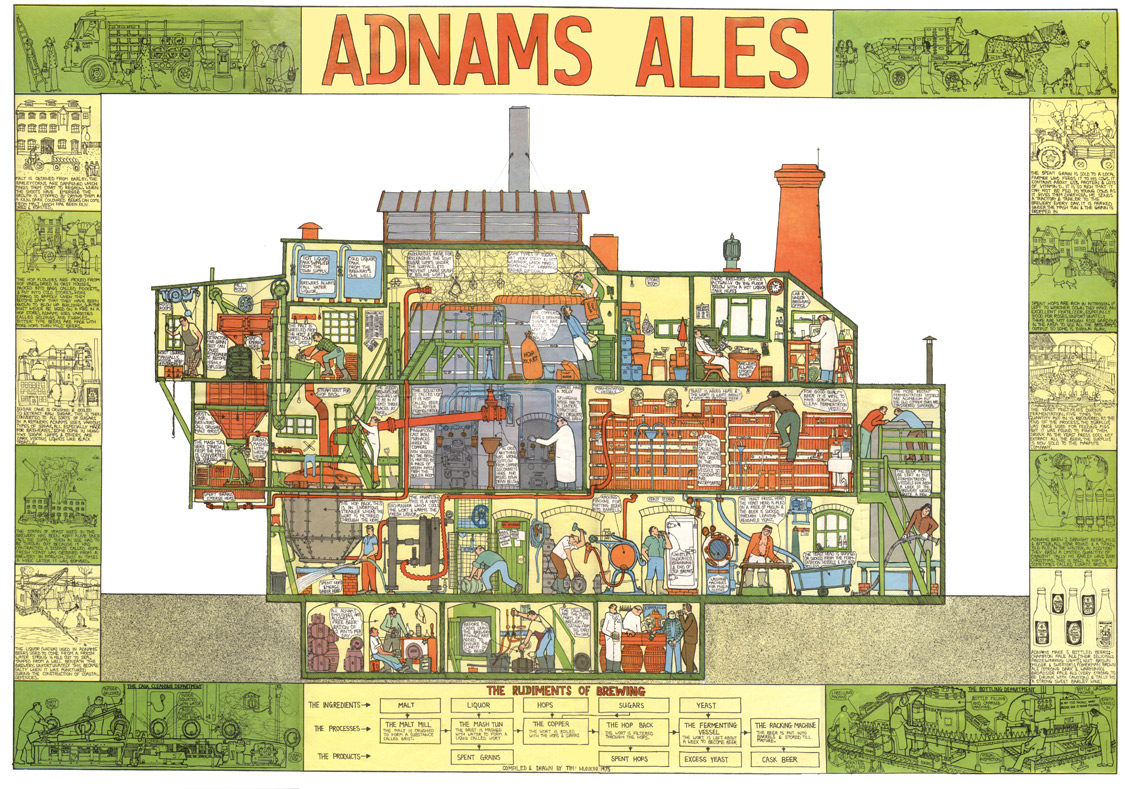

The poem is rooted the Virgilian georgic and Augustan literature; it is one of the first long poems published by Smart. The poem is literally about a hop garden, and, in the Virgilian tradition, attempts to instruct the audience in how to farm hops properly.

While the poem deals with natural and scientific principles, there is a strong autobiographical tendency. While the poem marks Smart’s classical and Latin influences, it also reveals Smart’s close association and influence with Miltonic poetic form, especially with the reliance on Miltonic blank verse.

The poem is divided into two books.

THE HOP-GARDEN.

A GEORGIC.

BOOK the FIRST.

THE land that answers best the farmer’s care,

And silvers to maturity the Hop:

When to inhume the plants; to turn the glebe;

And wed the tendrils to th’ aspiring poles:

Under what sign to pluck the crop, and how

To cure, and in capacious sacks infold,

I teach in verse Miltonian. Smile the muse,

And meditate an honour to that land

Where first I breath’d, and struggled into life

Impatient, Cantium, to be call’d thy son.

Oh! cou’d I emulate Dan Sydney’s muse,

Thy Sydney, Cantium—He from court retir’d

In Penshurst’s sweet elysium sung delight,

Sung transport to the soft-responding streams

Of Medway, and enliven’d all her groves:

While ever near him, goddess of the green,

Fair Pembroke [sister to Sir Philip Sydney] sat, and smil’d immense applause.

With vocal fascination charm’d the Hours

Unguarded left Heav’ns adamantine gate,

And to his lyre, swift as the winged sounds

That skim the air, danc’d unperceiv’d away.

Had I such pow’r, no peasants toil, no hops

Shou’d e’er debase my lay: far nobler themes,

The high atchievements of thy warrior kings

Shou’d raise my thoughts, and dignify my song.

But I, young rustic, dare not leave my cot,

For so enlarg’d a sphere—ah! muse beware,

Lest the loud larums of the braying trump,

Lest the deep drum shou’d drown thy tender reed,

And mar its puny joints: me, lowly swain,

Every unshaven arboret, me the lawns,

Me the voluminous Medway’s silver wave,

Content inglorious, and the hopland shades!

Yeomen, and countrymen attend my song:

Whether you shiver in the marshy Weald [commonly, but improperly call’d, the Wild],

Egregious shepherds of unnumber’d flocks,

Whose fleeces, poison’d into purple, deck

All Europe’s kings: or in fair Madum’s [Maidstone] vale

Imparadis’d, blest denizons, ye dwell;

Or Dorovernia’s [Canterbury] awful tow’rs ye love:

Or plough Tunbridgia’s salutiferous hills

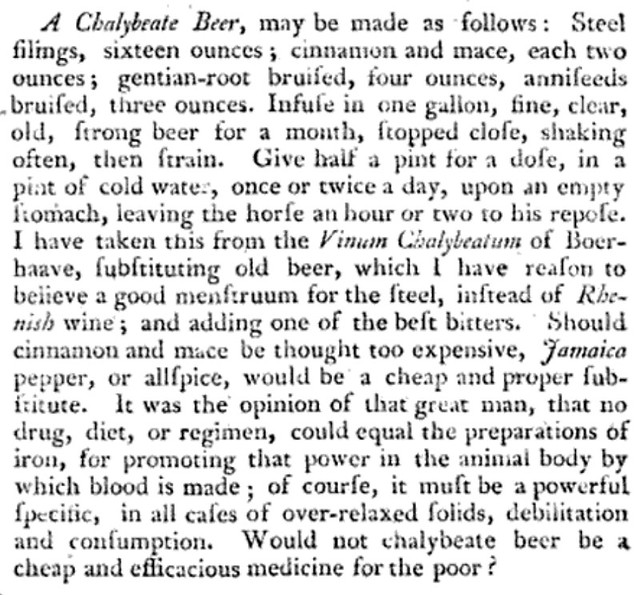

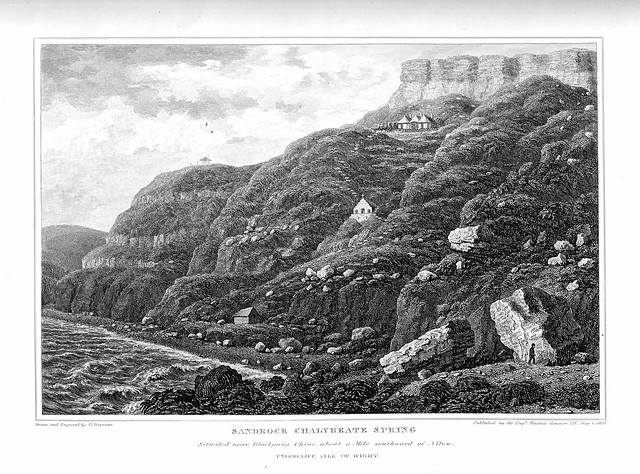

Industrious, and with draughts chalybiate heal’d,

Confess divine Hygeia’s blissful seat;

The muse demands your presence, ere she tune

Her monitory voice; observe her well,

And catch the wholesome dictates as they fall.

‘Midst thy paternal acres, Farmer, say

Has gracious heav’n bestow’d one field, that basks

Its loamy bosom in the mid-day sun,

Emerging gently from the abject vale,

Nor yet obnoxious to the wind, secure

There shall thou plant thy hop. This soil, perhaps,

Thou’lt say, will fill my garners. Be it so.

But Ceres, rural goddess, at the best

Meanly supports her vot’ry’, enough for her,

If ill-persuading hunger she repell,

And keep the soul from fainting: to enlarge,

To glad the heart, to sublimate the mind,

And wing the flagging spirits to the sky,

Require th’ united influence and aid

Of Bacchus, God of hops, with Ceres join’d

‘Tis he shall gen’rate the buxom beer.

Then on one pedestal, and hand in hand,

Sculptur’d in Parian stone (so gratitude

Indites) let the divine co-part’ners rise.

Stands eastward in thy field a wood? ’tis well.

Esteem it as a bulwark of thy wealth,

And cherish all its branches; tho’ we’ll grant,

Its leaves umbrageous may intercept

The morning rays, and envy some small share

Of Sol’s beneficence to the infant germ.

Yet grutch not that: when whistling Eurus comes,

With all his worlds of insects in thy lands

To hyemate, and monarchize o’er all

Thy vegetable riches, then thy wood

Shall ope it’s arms expansive, and embrace

The storm reluctant, and divert its rage.

Armies of animalc’les urge their way

In vain: the ventilating trees oppose

Their airy march. They blacken distant plains.

This site for thy young nursery obtain’d,

Thou hast begun auspicious, if the soil

(As sung before) be loamy; this the hop

Loves above others, this is rich, is deep,

Is viscous, and tenacious of the pole.

Yet maugre all its native worth, it may

Be meliorated with warm compost. See!

Yon craggy mountain [Boxley-Hill, which extends through great part of Kent], whose fastidious head,

Divides the star-set hemisphere above,

And Cantium’s plains beneath; the Appennine

Of a free Italy, whose chalky sides

With verdant shrubs dissimilarly gay,

Still captivate the eye, while at his feet

The silver Medway glides, and in her breast

Views the reflected landskip, charm’d she views

And murmurs louder ectasy below.

Here let us rest awhile, pleas’d to behold

Th’ all-beautiful horizon’s wide expanse,

Far as the eagle’s ken. Here tow’ring spires

First catch the eye, and turn the thoughts to heav’n.

The lofty elms in humble majesty

Bend with the breeze to shade the solemn groves,

And spread an holy darkness; Ceres there

Shines in her golden vesture. Here the meads

Enrich’d by Flora’s daedal hand, with pride

Expose their spotted verdure. Nor are you

Pomona absent; you ‘midst th’ hoary leaves

Swell the vermilion cherry; and on you trees

Suspend the pippen’s palatable gold.

There old Sylvanus in that moss-grown grot

Dwells with his wood-nymphs: they with chaplets green

And russet mantles oft bedight, aloft

From yon bent oaks, in Medway’s bosom fair

Wonder at silver bleak, and prickly pearch,

That swiftly thro’ their floating forests glide.

Yet not even these—these ever-varied scenes

Of wealth and pleasure can engage my eyes

T’ o’erlook the lowly hawthorn, if from thence

The thrush, sweet warbler, chants th’ unstudied lays

Which Phoebus’ self vaulting from yonder cloud

Refulgent, with enliv’ning ray inspires.

But neither tow’ring spires, nor lofty elms,

Nor golden Ceres, nor the meadows green,

Nor orchats, nor the russet-mantled nymphs,

Which to the murmurs of the Medway dance,

Nor sweetly warbling thrush, with half those charms

Attract my eyes, as yonder hop-land close,

Joint-work of art and nature, which reminds

The muse, and to her theme the wand’rer calls.

Here then with pond’rous vehicles and teams

Thy rustics send, and from the caverns deep

Command them bring the chalk: thence to the kiln

Convey, and temper with Vulcanian fires.

Soon as ’tis form’d, thy lime with bounteous hand

O’er all thy lands disseminate; thy lands

Which first have felt the soft’ning spade, and drank

The strength’ning vapours from nutricious marl.

This done, select the choicest hop, t’ insert

Fresh in the opening glebe. Say then, my muse,

Its various kinds, and from th’ effete and vile,

The eligible separate with care.

The noblest species is by Kentish wights

The Master-hop yclep’d. Nature to him

Has giv’n a stouter stalk, patient of cold,

Or Phoebus ev’n in youth, his verdant blood

In brisk saltation circulates and flows

Indesinently vigorous: the next

Is arid, fetid, infecund, and gross

Significantly styl’d the Fryar: the last

Is call’d the Savage, who in ev’ry wood,

And ev’ry hedge unintroduc’d intrudes.

When such the merit of the candidates,

Easy is the election; but, my friend

Would’st thou ne’er fail, to Kent direct thy way,

Where no one shall be frustrated that seeks

Ought that is great or good. Hail, Cantium, hail!

Illustrious parent of the finest fruits,

Illustrious parent of the best of men!

For thee Antiquity’s thrice sacred springs

Placidly stagnant at their fountain head,

I rashly dare to trouble (if from thence,

If ought for thy util’ty I can drain)

And in thy towns adopt th’ Ascraean muse.

Hail heroes, hail invaluable gems,

Splendidly rough within your native mines,

To luxury unrefined, better far

To shake with unbought agues in your weald,

Than dwell a slave to passion and to wealth,

Politely paralytic in the town!

Fav’rites of heav’n! to whom the general doom

Is all remitted, who alone possess

Of Adam’s sons fair Eden—rest ye here,

Nor seek an earthly good above the hop;

A good! untasted by your ancient kings,

And almost to your very sires unknown.

In those blest days when great Eliza reign’d

O’er the adoring nation, when fair peace

Or spread an unstain’d olive round the land,

Or laurell’d war did teach our winged fleets

To lord it o’er the world, when our brave sires

Drank valour from uncauponated beer;

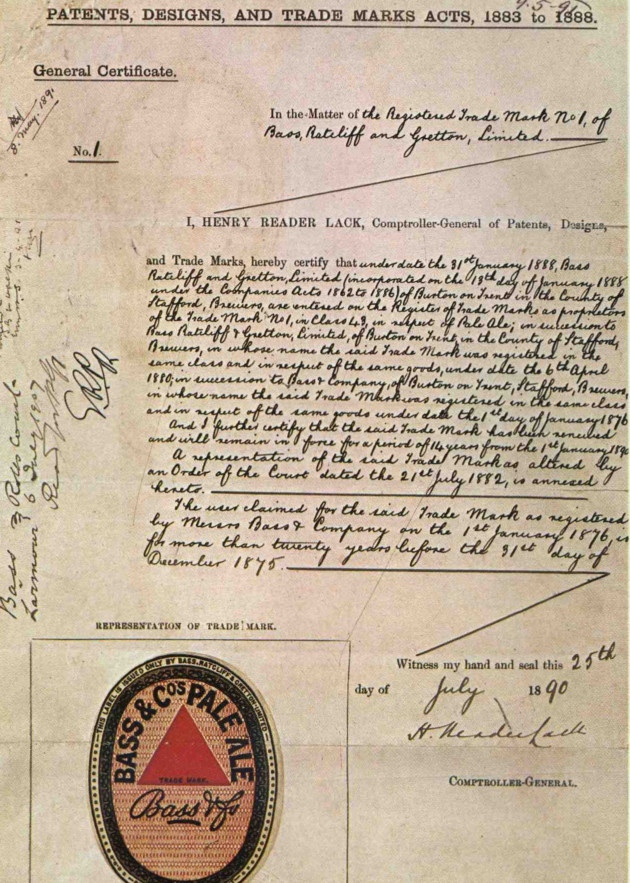

Then th’ hop (before an interdicted plant,

Shun’d like fell aconite) began to hang

Its folded floscles from the golden vine,

And bloom’d a shade to Cantium’s sunny shores

Delightsome, and in chearful goblets laught

Potent, what time Aquarius’ urn impends

To kill the dulsome day—potent to quench

The Syrian ardour, and autumnal ills

To heal with mild potations; sweeter far

Than those which erst the subtile Hengist mix’d

T’ inthral voluptuous Vortigern. He, with love

Emasculate and wine, the toils of war,

Neglected, and to dalliance vile and sloth

Emancipated, saw th’ incroaching Saxons

With unaffected eyes; his hand which ought

T’ have shook the spear of justice, soft and smooth,

Play’d ravishing divisions on the lyre:

This Hengist mark’d, and (for curs’d insolence

Soon fattens on impunity! and becomes

Briareus from a dwarf) fair Thanet gain’d.

Nor stopt he here; but to immense attempts

Ambition sky-aspiring led him on

Adventrous. He an only daughter rear’d,

Roxena, matchless maid! nor rear’d in vain.

Her eagle-ey’d callidity, grave deceit,

And fairy fiction rais’d above her sex,

And furnish’d her with thousand various wiles

Preposterous, more than female; wondrous fair

She was, and docile, which her pious nurse

Observ’d, and early in each female fraud

Her ‘gan initiate: well she knew to smile,

Whene’er vexation gall’d her; did she weep?

‘Twas not sincere, the fountains of her eyes

Play’d artificial streams, yet so well forc’d

They look’d like nature; for ev’n art to her

Was natural, and contrarieties

Seem’d in Roxena congruous and allied.

Such was she, when brisk Vortigern beheld,

Ill-fated prince! and lov’d her. She perceiv’d,

Soon she perceiv’d her conquest; soon she told,

With hasty joy transported, her old sire.

The Saxon inly smil’d, and to his isle

The willing prince invited, but first bad

The nymph prepare the potions; such as fire

The blood’s meand’ring rivulets, and depress

To love the soul. Lo! at the noon of night

Thrice Hecate invok’d the maid—and thrice

The goddess stoop’d assent; forth from a cloud

She stoop’d, and gave the philters pow’r to charm.

These in a splendid cup of burnish’d gold

The lovely sorceress mix’d, and to the prince

Health, peace, and joy propin’d, but to herself

Mutter’d dire exorcisms, and wish’d effect

To th’ love-creating draught: lowly she bow’d

Fawning insinuation bland, that might

Deceive Laertes’ son; her lucid orbs

Shed copiously the oblique rays; her face

Like modest Luna’s shone, but not so pale,

And with no borrow’d lustre; on her brow

Smil’d Fallacy, while summoning each grace,

Kneeling she gave the cup. The prince (for who!

Who cou’d have spurn’d a suppliant so divine?)

Drank eager, and in ecstasy devour’d

Th’ ambrosial perturbation; mad with love

He clasp’d her, and in Hymeneal bands

At once the nymph demanded and obtain’d.

Now Hengist, all his ample wish fulfill’d,

Exulted; and from Kent th’ uxorious prince

Exterminated, and usurp’d his seat.

Long did he reign; but all-devouring time

Has raz’d his palace walls—Perchance on them

Grows the green hop, and o’er his crumbled bust

In spiral twines ascends the scancile pole.—

But now to plant, to dig, to dung, to weed;

Tasks how indelicate? demand the muse.

Come, fair magician, sportive Fancy come,

With thy unbounded imagery; child of thought,

From thy aeriel citadel descend,

And (for thou canst) assist me. Bring with thee

Thy all-creative Talisman; with thee

The active spirits ideal, tow’ring flights,

That hover o’er the muse-resounding groves,

And all thy colourings, all thy shapes display.

Thou to be here, Experience, so shall I

My rules nor in low prose jejunely say,

Nor in smooth numbers musically err;

But vain is Fancy and Experience vain,

If thou, O Hesiod! Virgil of our land,

Or hear’st thou rather, Milton, bard divine,

Whose greatness who shall imitate, save thee?

If thou O Philips [Mr. John Philips, author of Cyder, a poem] fav’ring dost not hear

Me, inexpert of verse; with gentle hand

Uprear the unpinion’d muse, high on the top

Of that immeasurable mount, that far

Exceeds thine own Plinlimmon, where thou tun’st

With Phoebus’ self thy lyre. Give me to turn

Th’ unwieldly subject with thy graceful ease,

Extol its baseness with thy art; but chief

Illumine, and invigorate with thy fire.

When Phoebus looks thro’ Aries on the spring,

And vernal flow’rs promise the dulcet fruit,

Autumnal pride! delay not then thy setts

In Tellus’ facile bosom to depose

Timely: if thou art wise the bulkiest chuse:

To every root three joints indulge, and form

The Quincunx with well regulated hills.

Soon from the dung-enriched earth, their heads

Thy young plants will uplift their virgin arms,

They’ll stretch, and marriageable claim the pole.

Nor frustrate thou their wishes, so thou may’st

Expect an hopeful issue, jolly Mirth,

Sister of taleful Jocus, tuneful Song,

And fat Good-nature with her honest face.

But yet in the novitiate of their love,

And tenderness of youth suffice small shoots

Cut from the widow’d willow, nor provide

Poles insurmountable as yet. ‘Tis then

When twice bright Phoebus’ vivifying ray,

Twice the cold touch of winter’s icy hand,

They’ve felt; ’tis then we fell sublimer props.

‘Tis then the sturdy woodman’s axe from far

Resounds, resounds, and hark! with hollow groans

Down tumble the big trees, and rushing roll

O’er the crush’d crackling brake, while in his cave

Forlorn, dejected, ‘midst the weeping dryads

Laments Sylvanus for his verdant care.

The ash, or willow for thy use select,

Or storm-enduring chesnut; but the oak

Unfit for this employ, for nobler ends

Reserve untouch’d; she when by time matur’d,

Capacious, of fome British demi-god,

Vernon, or Warren, shall with rapid wing

Infuriate, like Jove’s armour-bearing bird,

Fly on thy foes; They, like the parted waves,

Which to the brazen beak murmuring give way

Amaz’d, and roaring from the fight recede.—

In that sweet month, when to the list’ning swains

Fair Philomel fings love, and every cot

With garlands blooms bedight, with bandage meet

The tendrils bind, and to the tall pole tie,

Else soon, too soon their meretricious arms

Round each ignoble clod they’ll fold, and leave

Averse the lordly prop. Thus, have I heard

Where there’s no mutual tye, no strong connection

Of love-conspiring hearts, oft the young bride

Has prostituted to her slaves her charms,

While the infatuated lord admires

Fresh-budding sprouts, and issue not his own.

Now turn the glebe: soon with correcting hand

When smiling June in jocund dance leads on

Long days and happy hours, from ev’ry vine

Dock the redundant branches, and once more

With the sharp spade thy numerous acres till.

The shovel next must lend its aid, enlarge

The little hillocks, and erase the weeds.

This in that month its title which derives

From great Augustus’ ever sacred name!

Sovereign of Science! master of the Muse!

Neglected Genius’ firm ally! Of worth

Best judge, and best rewarder, whose applause

To bards was fame and fortune! O! ’twas well,

Well did you too in this, all glorious heroes!

Ye Romans!—on Time’s wing you’ve stamp’d his praise,

And time shall bear it to eternity.

Now are our lab’rours crown’d with their reward,

Now bloom the florid hops, and in the stream

Shine in their floating silver, while above

T’embow’ring branches culminate, and form

A walk impervious to the sun; the poles

In comely order stand; and while you cleave

With the small skiff the Medway’s lucid wave,

In comely order still their ranks preserve,

And seem to march along th’ extensive plain.

In neat arrangement thus the men of Kent,

With native oak at once adorn’d and arm’d,

Intrepid march’d; for well they knew the cries

Of dying Liberty, and Astraea’s voice,

Who as she fled, to echoing woods complain’d

Of tyranny, and William; like a god,

Refulgent stood the conqueror, on his troops

He sent his looks enliv’ning as the sun’s,

But on his foes frown’d agony, frown’d death.

On his left side in bright emblazonry

His falchion burn’d; forth from his sevenfold shield

A basilisk shot adamant; his brow

Wore clouds of fury!—on that with plumage crown’d

Of various hue sat a tremendous cone:

Thus sits high-canopied above the clouds,

Terrific beauty of nocturnal skies,

Northern Aurora [Aurora Borealis, or lights in the air; a phoenomenon which of late years has been very frequent here, and in all the more northern countries]; she thro’ th’ azure air

Shoots, shoots her trem’lous rays in painted streaks

Continual, while waving to the wind

O’er Night’s dark veil her lucid tresses flow.

The trav’ler views th’ unseasonable day

Astound, the proud bend lowly to the earth,

The pious matrons tremble for the world.

But what can daunt th’ insuperable souls

Of Cantium’s matchless sons? On they proceed,

All innocent of fear; each face express’d

Contemptuous admiration, while they view’d

The well-fed brigades of embroider’d slaves

That drew the sword for gain. First of the van,

With an enormous bough, a shepherd swain

Whistled with rustic notes; but such as show’d

A heart magnanimous: The men of Kent

Follow the tuneful swain, while o’er their heads

The green leaves whisper, and the big boughs bend.

‘Twas thus the Thracian, whose all-quick’ning lyre

The floods inspir’d, and taught the rocks to feel,

Play’d before dancing Haemus, to the tune,

The lute’s soft tune! The flutt’ring branches wave,

The rocks enjoy it, and the rivulets hear,

The hillocks skip, emerge the humble vales,

And all the mighty mountain nods applause.

The conqueror view’d them, and as one that sees

The vast abrupt of Scylla, or as one

That from th’ oblivious Lethaean streams

Has drank eternal apathy, he stood.

His host an universal panic seiz’d

Prodigious, inopine; their armour shook,

And clatter’d to the trembling of their limbs;

Some to the walking wilderness gan run

Confus’d, and in th’ inhospitable shade

For shelter sought—Wretches! they shelter find,

Eternal shelter in the arms of death!

Thus when Aquarius pours out all his urn

Down on some lonesome heath, the traveller

That wanders o’er the wint’ry waste, accepts

The invitation of some spreading beech

Joyous; but soon the treach’rous gloom betrays

Th’ unwary visitor, while on his head

Th’ inlarging drops in double show’rs descend.

And now no longer in disguise the men

Of Kent appear; down they all drop their boughs,

And shine in brazen panoply divine.

Enough—Great William (for full well he knew

How vain would be the contest) to the sons

Of glorious Cantium, gave their lives, and laws,

And liberties secure, and to the prowess

Of Kentish wights, like Caesar, deign’d to yield.

Caesar and William! Hail immortal worthies,

Illustrious vanquish’d! Cantium, if to them,

Posterity will all her chiefs unborn,

Ought similar, ought second has to boast.

Once more (so prophecies the Muse) thy sons

Shall triumph, emulous of their sires—till then

With olive, and with hop-land garlands crown’d,

O’er all thy land reign Plenty, reign fair Peace.

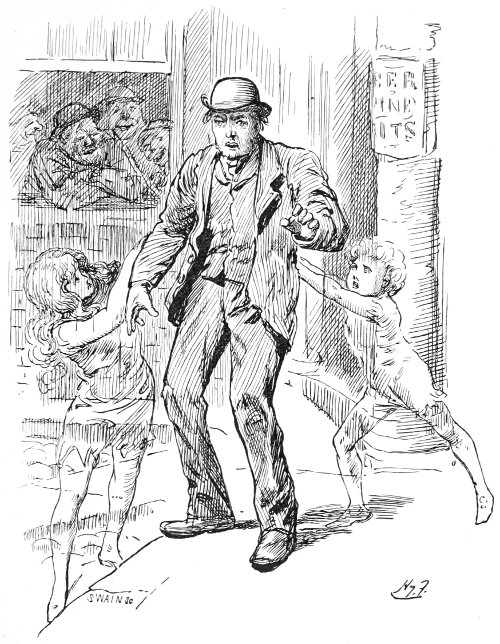

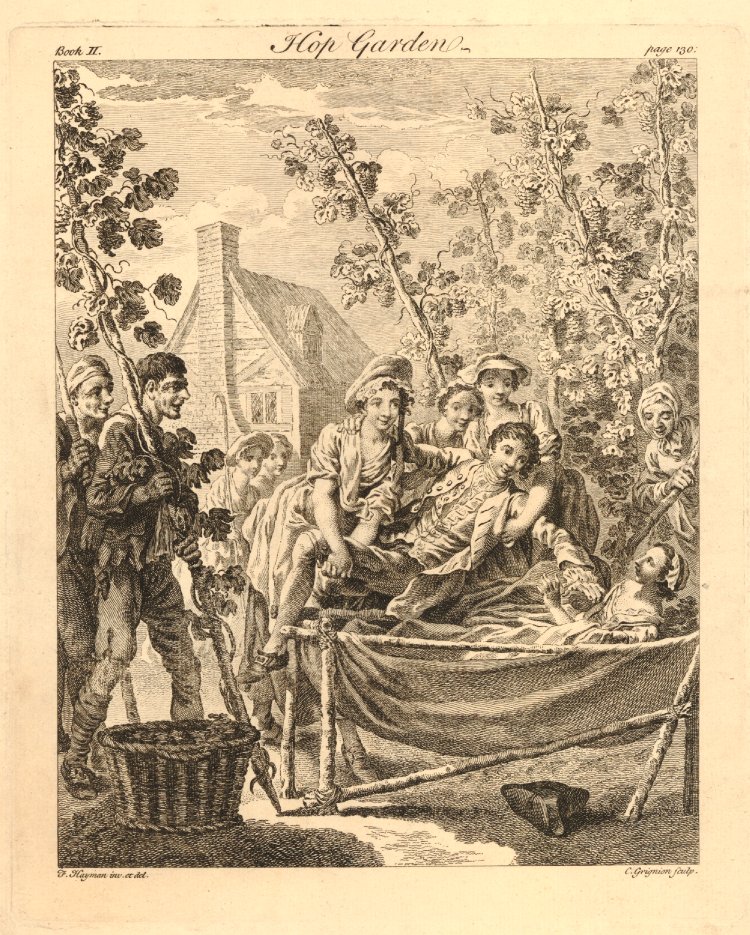

This illustration accompanied the second book. The British Museum has it in their collection, and they describe it as “a woman sitting in a vat, two others lifting a man in to join her, an amused crowd looking on.” Interestingly enough, the illustration appears to show an old ritual associated with hop-picking. According to the poem, it seems to involve a “festive ritual that played a part in the annual hop harvest, where a young woman, and a young man, are placed in a container of hops and covered up by it.”

Many years later, in 1931, George Orwell went hop-picking and made the following entry in his diary for September 19, 1931:

On the last morning, when we had picked the last field, there was a queer game of catching the women and putting them in the bins. Very likely there will be something about this in the Golden Bough. It is evidently an old custom, and all harvests have some custom of this kind attached to them.

The only reference I could find in the Golden Bough was this. “In hop-picking, if a well-dressed stranger passes the hop-yard, he is seized by the women, tumbled into the bin, covered with leaves, and not released till he has paid a fine.” One scholar speculates:

In any case, the ritual in the oldest version – Smart’s – seems to be some kind of fertility ritual: a male and a female hop picker are submerged together in a container of hops, which are the bounty of the harvest. It also seems to include some kind of wealth-redistribution element, where the other pickers claim a “largesse” or “fine” from those submerged. Whether it was for the honor, or just because they were the most efficient pickers, I don’t know, but it’s interesting either way. Ron Bateman notes that at least in Orwell’s day, the ritual took place on the last day of hop-picking, which I think strongly supports the idea of it being some vestige of a pagan fertility rite (or, even, the whole of the rite, with its purpose forgotten): having completed the harvest, the rite would help appease the field, its spirits, the gods, etc. to ensure the next year’s harvest would also be plentiful.

Anyway, here’s the second part of the poem.

THE HOP-GARDEN.

A GEORGIC.

BOOK the SECOND.

AT length the Muse her destin’d task resumes

With joy; agen o’er all her hop-land groves

She longs t’ expatiate free of wing. Long while

For a much-loving, much-lov’d youth she wept,

And sorrow’d silence o’er th’ untimely urn.

Hush then, effeminate sobs; and thou, my heart,

Rebel to grief no more—And yet a while,

A little while, indulge the friendly tears.

O’er the wild world, like Noah’s dove, in vain

I seek the olive peace, around me wide

See! see! the wat’ry waste—In vain, forlorn

I call the Phoenix fair Sincerity;

Alas!—extinguish’d to the skies she fled,

And left no heir behind her. Where is now

Th’ eternal smile of goodness? Where is now

That all-extensive charity of soul,

So rich in sweetness, that the classic sounds

In elegance Augustan cloath’d, the wit

That flow’d perennial, hardly were observ’d,

Or, if observ’d, set off a brighter gem.

How oft, and yet how seldom did it seem!

Have I enjoy’d his converse?—When we met,

The hours how swift they sweetly fled, and till

Agen I saw him, how they loiter’d. Oh!

THEOPHILUS [Mr. Theophilus Wheeler, of Christ-College, Cambridge], thou dear departed soul,

What flattering tales thou told’st me? How thou’dst hail

My Muse, and took’st imaginary walks

All in my hopland groves! Stay yet, oh stay!

Thou dear deluder, thou hast seen but half—

He’s gone! and ought that’s equal to his praise

Fame has not for me, tho’ she prove most kind.

Howe’er this verse be sacred to thy name,

These tears, the last sad duty of a friend.

Oft i’ll indulge the pleasurable pain

Of recollection; oft on Medway’s banks

I’ll muse on thee full pensive; while her streams

Regardful ever of my grief, shall flow

In sullen silence silverly along

The weeping shores—or else accordant with

My loud laments, shall ever and anon

Make melancholy music to the shades,

The hopland shades, that on her banks expose

Serpentine vines and flowing locks of gold.

Ye smiling nymphs, th’ inseparable train

Of saffron Ceres; ye, that gamesome dance,

And sing to jolly Autumn, while he stands

With his right hand poizing the scales of heav’n,

And with his left grasps Amalthea’s horn:

Young chorus of fair bacchanals, descend,

And leave a while the sickle; yonder hill,

Where stand the loaded hop-poles, claims your care.

There mighty Bacchus stradling cross the bin,

Waits your attendance—There he glad reviews

His paunch, approaching to immensity

Still nearer, and with pride of heart surveys

Obedient mortals, and the world his own.

See! from the great metropolis they rush,

Th’ industrious vulgar. They, like prudent bees,

In Kent’s wide garden roam, expert to crop

The flow’ry hop, and provident to work,

Ere winter numb their sunburnt hands, and winds

Engoal them, murmuring in their gloomy cells.

From these, such as appear the rest t’ excell

In strength and young agility, select.

These shall support with vigour and address

The bin-man’s weighty office; now extract

From the sequacious earth the pole, and now

Unmarry from the closely clinging vine.

O’er twice three pickers, and no more, extend

The bin-man’s sway; unless thy ears can bear

The crack of poles continual, and thine eyes

Behold unmoved the hurrying peasant tear

Thy wealth, and throw it on the thankless ground.

But first the careful planter will consult

His quantity of acres, and his crop,

How many and how large his kilns; and then

Proportion’d to his wants the hands provide.

But yet, of greater consequence and cost,

One thing remains unsung, a man of faith

And long experience, in whose thund’ring voice

Lives hoarse authority, potent to quell

The frequent frays of the tumultuous crew.

He shall preside o’er all thy hop-land store,

Severe dictator! His unerring hand,

And eye inquisitive, in heedful guise,

Shall to the brink the measure fill, and fair

On the twin registers the work record.

And yet I’ve known them own a female reign,

And gentle Marianne’s [the author’s youngest Sister] soft Orphean voice

Has hymn’d sweet lessons of humanity

To the wild brutal crew. Oft her command

Has sav’d the pillars of the hopland state,

The lofty poles from ruin, and sustain’d,

Like ANNA, or ELIZA, her domain,

With more than manly dignity. Oft I’ve seen,

Ev’n at her frown the boist’rous uproar cease,

And the mad pickers, tam’d to diligence,

Cull from the bin the sprawling sprigs, and leaves

That stain the sample, and its worth debase.

All things thus settled and prepared, what now

Can let the planters purposes? Unless

The Heav’ns frown dissent, and ominous winds

Howl thro’ the concave of the troubled sky.

And oft, alas! the long experienc’d wights

(Oh! could they too prevent them) storms foresee.

For, as the storm rides on the rising clouds,

Fly the fleet wild-geese far away, or else

The heifer towards the zeinth rears her head,

And with expanded nostrils snuffs the air:

The swallows too their airy circuits weave,

And screaming skim the brook; and fen-bred frogs

Forth from their hoarse throats their old grutch recite:

Or from her earthly coverlets the ant

Heaves her huge eggs along the narrow way:

Or bends Thaumantia’s variegated bow

Athwart the cope of heav’n: or sable crows

Obstreperous of wing, in crouds combine:

Besides, unnumber’d troops of birds marine,

And Asia’s feather’d flocks, that in the muds

Of flow’ry-edg’d Cayster wont to prey,

Now in the shallows duck their speckled heads,

And lust to lave in vain, their unctious plumes

Repulsive baffle their efforts: Next hark

How the curs’d raven, with her harmful voice,

Invokes the rain, ahd croaking to herself,

Struts on some spacious solitary shore.

Nor want thy servants and thy wife at home

Signs to presage the show’r; for in the hall

Sheds Niobe her prescious tears, and warns

Beneath thy leaden tubes to fix the vase,

And catch the falling dew-drops, which supply

Soft water and salubrious, far the best

To soak thy hops, and brew thy generous beer.

But tho’ bright Phoebus smile, and in the skies

The purple-rob’d serenity appear;

Tho’ every cloud be fled, yet if the rage

Of Boreas, or the blasting East prevail,

The planter has enough to check his hopes,

And in due bounds confine his joy; for see

The ruffian winds, in their abrupt career,

Leave not a hop behind, or at the best

Mangle the circling vine, and intercept

The juice nutricious: Fatal means, alas!

Their colour and condition to destroy.

Haste then, ye peasants; pull the poles, the hops;

Where are the bins? Run, run, ye nimble maids,

Move ev’ry muscle, ev’ry nerve extend,

To save our crop from ruin, and ourselves.

Soon as bright Chanticleer explodes the night

With flutt’ring wings, and hymns the new-born day,

The bugle-horn inspire, whose clam’rous bray

Shall rouse from sleep the rebel rout, and tune

To temper for the labours of the day.

Wisely the several stations of the bins

By lot determine. Justice this, and this

Fair Prudence does demand; for not without

A certain method cou’dst thou rule the mob

Irrational, nor every where alike

Fair hangs the hop to tempt the picker’s hand.

Now see the crew mechanic might and main

Labour with lively diligence, inspir’d

By appetie of gain and lust of praise:

What mind so petty, servile, and debas’d,

As not to know ambition? Her great sway

From Colin Clout to Emperors she exerts.

To err is human, human to be vain.

‘Tis vanity, and mock desire of fame,

That prompts the rustic, on the steeple top

Sublime, to mark the outlines of his shoe,

And in the area to engrave his name.

With pride of heart the churchwarden surveys,

High o’er the bellfry, girt with birds and flow’rs,

His story wrote in capitals: “‘Twas I

“That bought the font; and I repair’d the pews.”

With pride like this the emulating mob

Strive for the mastery—who first may fill

The bellying bin, and cleanest cull the hops.

Nor ought retards, unless invited out

By Sol’s declining, and the evening’s calm,

Leander leads Laetitia to the scene

Of shade and fragrance—Then th’ exulting band

Of pickers male and female, seize the fair

Reluctant, and with boist’rous force and brute,

By cries unmov’d, they bury her in the bin.

Nor does the youth escape—him too they seize,

And in such posture place as best may serve

To hide his charmer’s blushes. Then with shouts

They rend the echoing air, and from them both

(So custom has ordain’d) a largess claim.

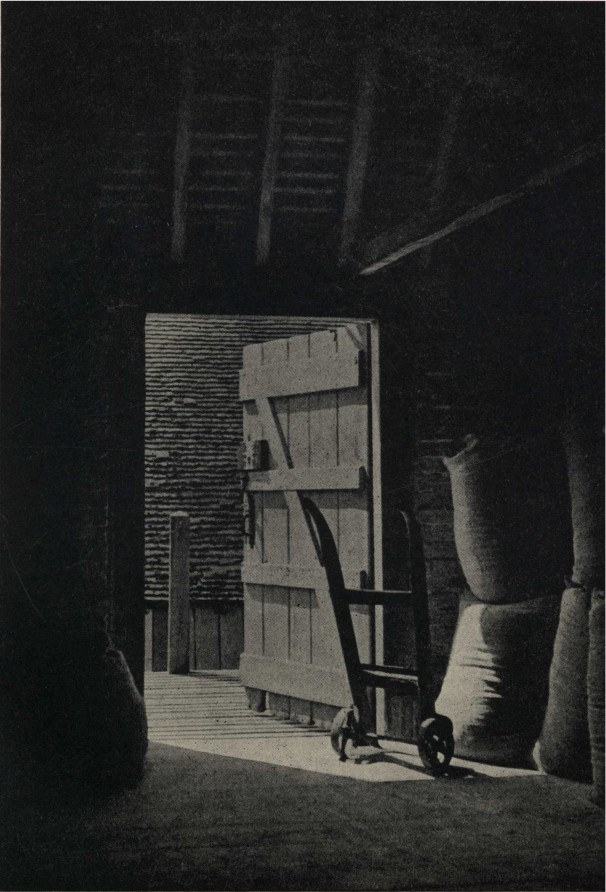

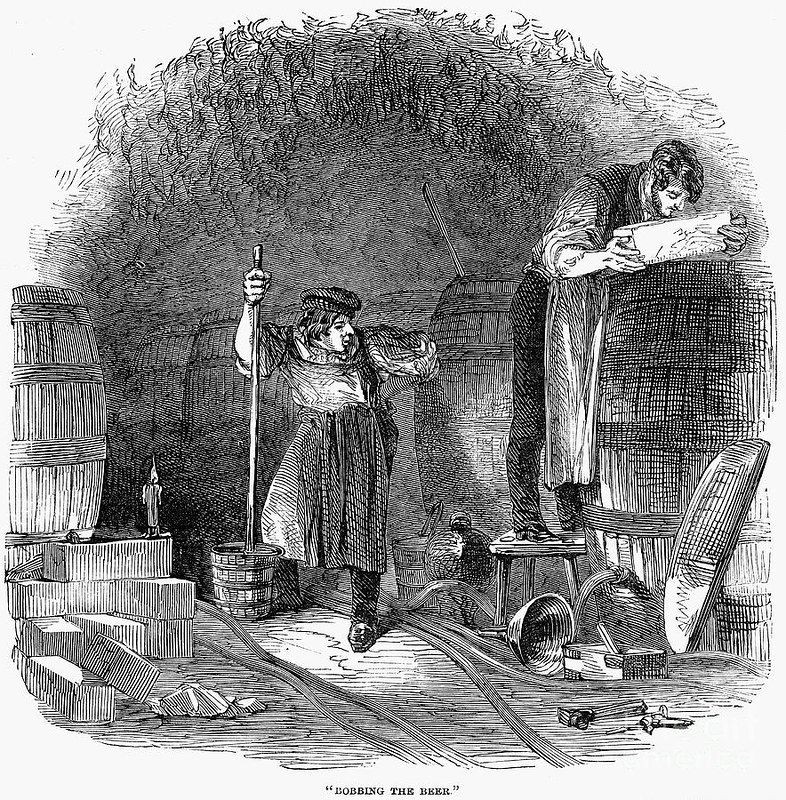

Thus much be sung of picking—next succeeds

Th’ important care of curing—Quit the field,

And at the kiln th’ instructive muse attend.

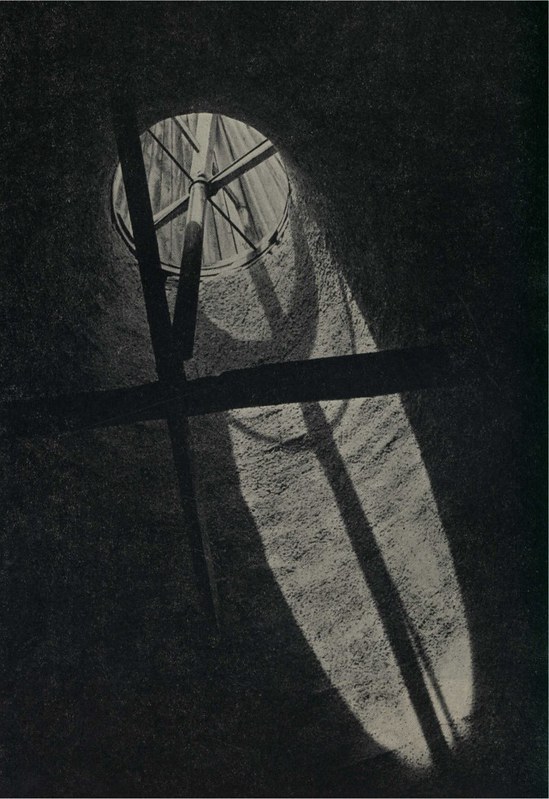

On your hair-cloth eight inches deep, nor more,

Let the green hops lie lightly; next expand

The smoothest surface with the toothy rake.

Thus for is just above; but more it boots

That charcoal flames burn equably below,

The charcoal flames, which from thy corded wood,

Or antiquated poles, with wond’rous skill,

The sable priests of Vulcan shall prepare.

Constant and moderate let the heat ascend;

Which to effect, there are, who with success

Place in the kiln the ventilating fan.

Hail, learned, useful man! [Dr. Hales] whose head and heart

Conspire to make us happy, deign t’ accept

One honest verse; and if thy industry

Has serv’d the hopland cause, the Muse forebodes

This sole invention, both in use and fame,

The mystic fan of Bacchus shall exceed.

When the fourth hour expires, with careful hand

The half-bak’d hops turn over. Soon as time

Has well exhausted twice two glasses more,

They’ll leap and crackle with their bursting seeds,

For use domestic, or for sale mature.

There are, who in the choice of cloth t’enfold

Their wealthy crop, the viler, coarser sort,

With prodigal oeconomy prefer:

All that is good is cheap, all dear that’s base.

Besides, the planter shou’d a bait prepare,

T’ intrap the chapman’s notice, and divert

Shrewd Observation from her busy pry.

When in the bag thy hops the rustic treads,

Let him wear heel-less sandals; nor presume

Their fragrancy barefooted to defile:

Such filthy ways for slaves in Malaga

Leave we to practise—Whence I’ve often seen,

When beautiful Dorinda’s iv’ry hands

Had built the pastry-fabric (food divine

For Christmas gambols and the hour of mirth)

As the dry’d foreign fruit, with piercing eye,

She cull’d suspicious—lo! she starts, she frowns

With indignation at a negro’s nail.

Should’st thou thy harvest for the mart design,

Be thine own factor; nor employ those drones

Who’ve stings, but make no honey, felfish slaves!

That thrive and fatten on the planter’s toil.

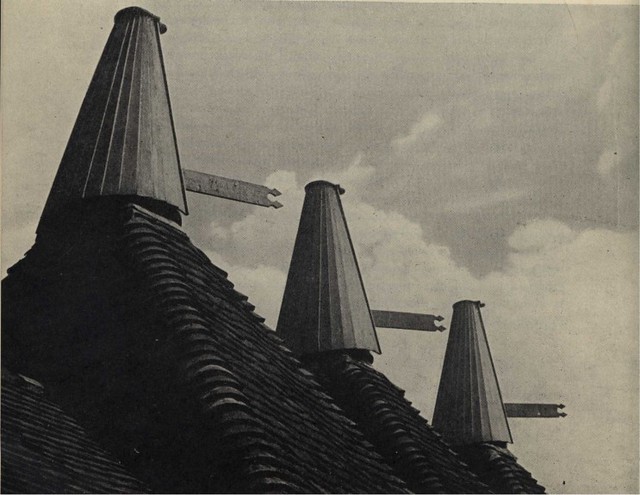

What then remains unsung? unless the care

To stack thy poles oblique in comely cones,

Lest rot or rain destroy them—’Tis a sight

Most seemly to behold, and gives, O Winter!

A landskip not unpleasing ev’n to thee.

And now, ye rivals of the hopland state,

Madum and Dorovernia rejoice,

How great amidst such rivals to excel!

Let Grenovicum [Greenwich, where Queen Elizabeth was born] boast (for boast she may)

The birth of great Eliza.—Hail, my queen!

And yet I’ll call thee by a dearer name,

My countrywoman, hail! Thy worth alone

Gives fame to worlds, and makes whole ages glorious!

Let Sevenoaks vaunt the hospitable seat

Of Knoll [the seat of the Duke of Dorset] most ancient: Awefully, my Muse,

These social scenes of grandeur and delight,

Of love and veneration, let me tread.

How oft beneath you oak has amorous Prior

Awaken’d Echo with sweet Chloe’s name!

While noble Sackville heard, hearing approv’d,

Approving, greatly recompens’d. But he,

Alas! has number’d with th’ illustrious dead,

And orphan merit has no guardian now!

Next Shipbourne, tho’ her precincts are confin’d

To narrow limits, yet can shew a train

Of village beauties, pastorally sweet,

And rurally magnificent. Here Fairlawn [the seat of Lord Vane]

Opes her delightful prospects: Dear Fairlawn

There, where at once at variance and agreed,

Nature and art hold dalliance. There where rills

Kiss the green drooping herbage, there where trees,

The tall trees-tremble at th’ approach of heav’n,

And bow their salutation to the sun,

Who fosters all their foliage—These are thine,

Yes, little Shipbourne, boast that these are thine—

And if—But oh!—and if ’tis no disgrace,

The birth of him who now records thy praise.

Nor shalt thou, Mereworth, remain unsung,

Where noble Westmoreland, his country’s friend,

Bids British greatness love the silent shade,

Where piles superb, in classic elegance,

Arise, and all is Roman, like his heart.

Nor Chatham, tho’ it is not thine to shew

The lofty forest or the verdant lawns,

Yet niggard silence shall not grutch thee praise.

The lofty forests by thy sons prepar’d

Becomes the warlike navy, braves the floods,

And gives Sylvanus empire in the main.

Oh that Britannia, in the day of war,

Wou’d not alone Minerva’s valour trust,

But also hear her wisdom! Then her oaks

Shap’d by her own mechanics, wou’d alone

Her island fortify, and fix her fame;

Nor wou’d she weep, like Rachael, for her sons,

Whose glorious blood, in mad profusion,

In foreign lands is shed—and shed in vain.

Now on fair Dover’s topmost cliff I’ll stand,

And look with scorn and triumph on proud France.

Of yore an isthmus jutting from this coast,

Join’d the Britannic to the Gallic shore;

But Neptune on a day, with fury fir’d,

Rear’d his tremendous trident, smote the earth,

And broke th’ unnatural union at a blow.—

“‘Twixt you and you, my servants and my sons,

“Be there (he cried) eternal discord—France

“Shall bow the neck to Cantium’s peerless offspring,

“And as the oak reigns lordly o’er the shrub,

“So shall the hop have homage from the vine.”