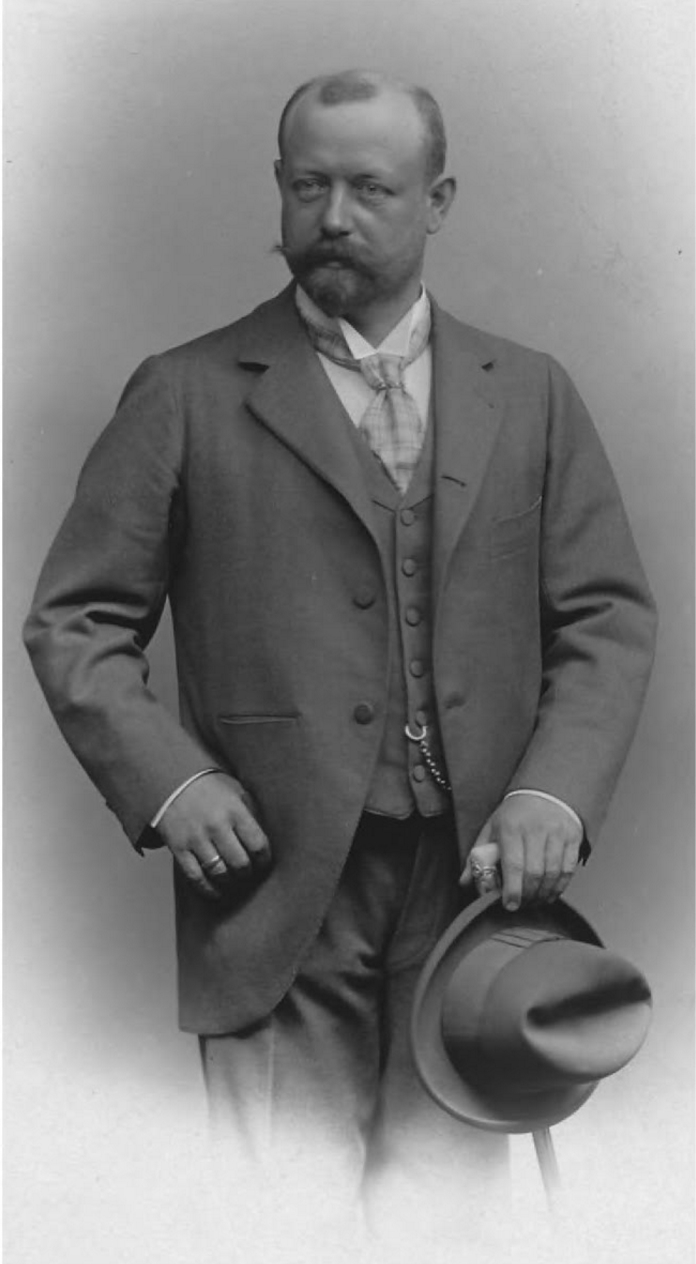

Today is the birthday of Michael Sieben (January 3, 1835-September 5, 1925). He was born in Ebersheim, Germany, but came to America when he was 25, in 1860. In 1865, he bought the James L. Hoerber Brewery, running it until 1875, when he built a new brewery which he named the Michael Sieben Brewery. Twenty years later he sold that brewery to the Excelsior Brewing Co., but promptly built another brewery, selling that one to United Breweries Co. in 1898, though he remained its manager of the Sieben’s Branch. A brewery bearing his name continued on in Chicago until prohibition, was briefly open during it, and re-opened afterwards in 1933 as Sieben’s Brewery Co., which remained in business until 1967.

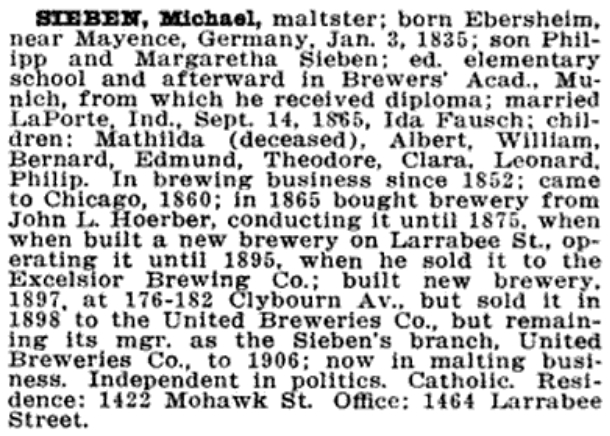

This biography of Sieben is from “The Book of Chicagoans: A Biographical Dictionary of Leading Living Men of the City of Chicago, edited by Albert Nelson Marquis, and published in 1911:

The one hundreth birthday anniversary of Michael Sieben, the founder of the brewery which is now known all over the world, is celebrated these days by the Chicago Sieben Brewery Company, 1470 Larrabee Street. For the festive occasion an especially tasteful beer, the Sieben Centennial beer, was put on the market. It was made after a receipt known to the family for seventy years.

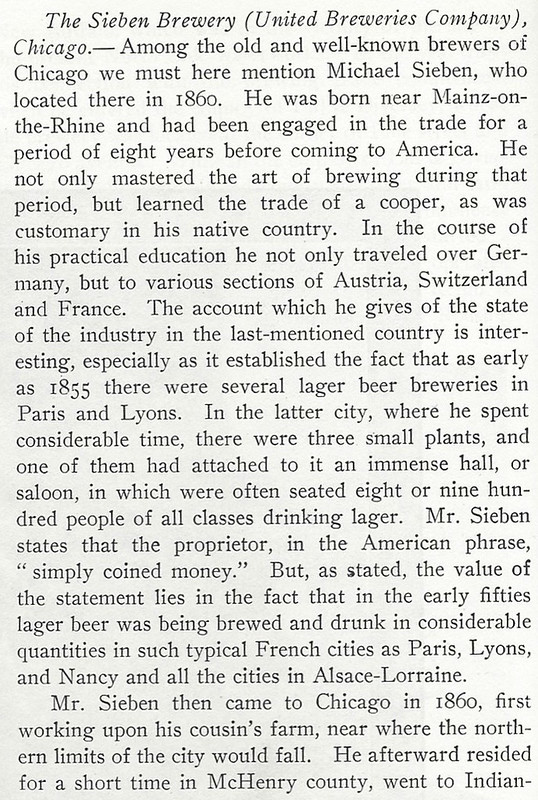

Michael Sieben was born on January 3, 1835, in Ebersheim, near Mainz, Germany, and died in Chicago September 5, 1925, at the age of ninety years. He learned the honorable art of beer brewing in Mainz, Germany, and as brewer’s and cooper’s assistant he journeyed through Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. For two years he worked at Lyons, Maney, and Dijon until the wanderlust urged him to go to the unknown land on the other side of the big pond.

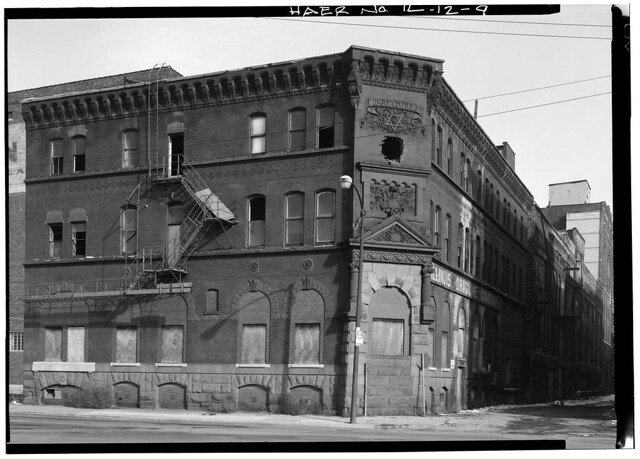

Michael Sieben came in the year 1860 to America. During the succeeding five years, he worked as malster and brewer’s assistant, then as master brewer, and later as manager in Chicago, Indianapolis, Cincinnati, and Boston. In the year 1865, he returned to Chicago and founded here the Sieben brewery in the then Griswold Street. In the year 1876, the brewery moved to Larrabee Street, south of Blackhawk Street, at which place it is still operating today.

From the marriage of Michael Sieben and his wife Ida, nee Fausch, came seven children, of whom two sons, William and Bernard, are in charge of the brewery today.

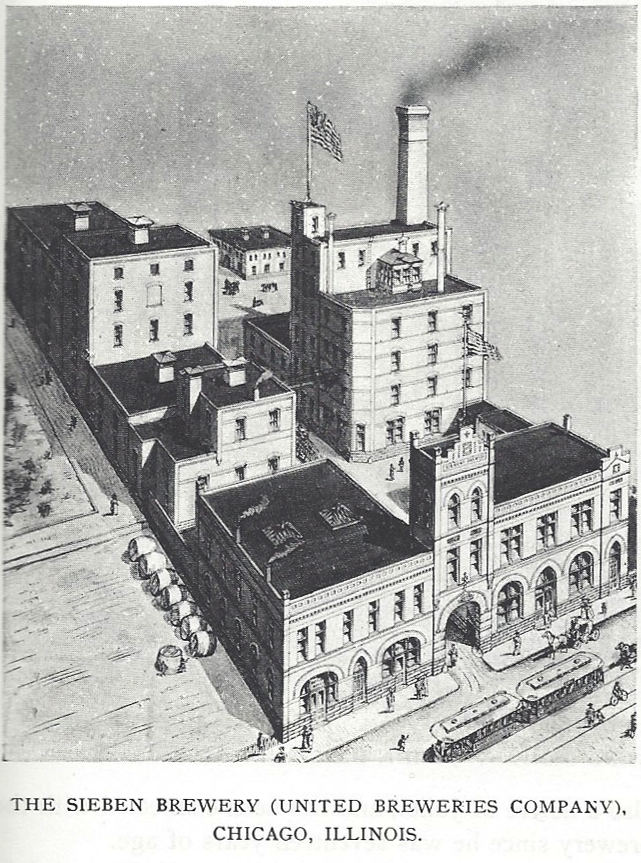

This account of the brewery is from “100 Years of Brewing,” published in 1903:

Around 2006, a group of investor’s tried to bring back the Sieben’s beer brand, but the last time the website was updated was 2009, so I don’t think they were successful in the long run. And in fact, the home page states that it’s “off the market.” But this account of Sieben is from their website:

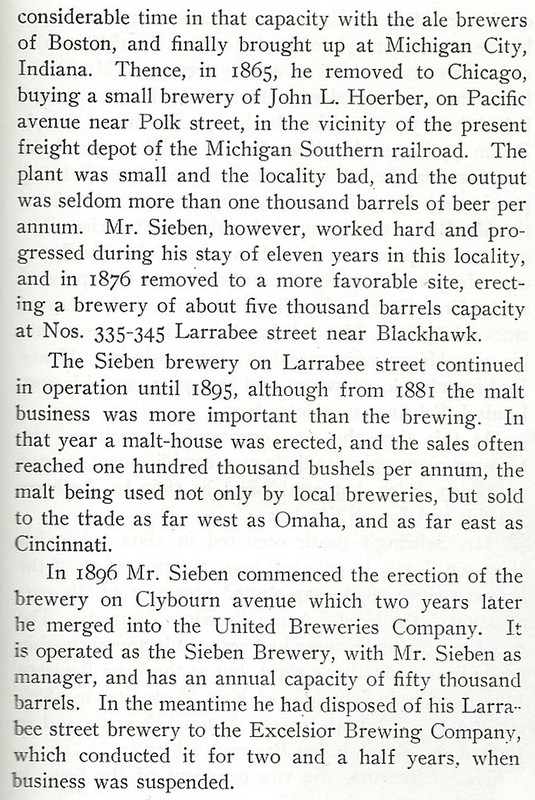

Michael Sieben immigrated to the United States in 1860 from Ebersheim, Germany a village southwest of Mainz. In 1865 Michael founded the Michael SiebenBrewery, located on Pacific Avenue near Clark and Polk Streets in Chicago. That street is now the section of La Salle St. south of Congress Parkway. In 1871, the brewery was narrowly missed by the Great Chicago Fire due to a change in wind direction. In 1876 the brewery was relocated to 1466 Larrabee Street, just a short walk from where the Larrabee-Ogden station of the Chicago “L” Transit System would be built in 1900.

In 1896 Michael Sieben built a larger brewery on Clybourn Avenue, not far from the Larrabee Street location. In 1898 it was merged into the United Breweries Company. By 1903, Michael Sieben was back in the original Larrabee Street location and changed the name of his company to the Sieben´s Brewery Company. Michael Sieben´s wish was that the brewery bearing his name not be owned by anyone outside the Sieben family, perhaps due to the short alliance he had with United Breweries Company that this wish came into effect.

During the years of Prohibition 1920-1933 the Sieben family was out of the beer business. The years of Prohibition gave brewers few choices, some started to produce soda and/or near beer (a nonalcoholic beer) or just closed forever. Some brewers however, were faced with a couple of other choices, sell or lease their brewery. The Sieben´s were faced with this choice and decided to lease out the brewery to an entity which was supposed to be engaged in producing a nonalcoholic beer. This new company was called the George Frank Brewery and is said to be owned in partnership by Dion O´Banion (head of the north side gang) and Johnny Torrio (head of the south side gang). The story goes, that O´Banion calls up Torrio and said that he is tired of the bootleg business and wants to retire to his place in Colorado. O´Banion offered to sell Torrio, his share of the brewery for $500,000.00, Torrio agreed. Dion O´Banion was aware of the penalties for prohibition convictions.

The first, a mere slap on the hand. The second, put you away for nine months and O´Banion knew that Torrio had one conviction against him. Dion O´Banion also had information that the Chicago Police Department was to raid the brewery the day of the meeting. On May 19, 1924 the two men met at the Sieben´s Brewery. Johnny Torrio, handed Dion O´Banion a case with $500,000.00 in cash and in came the police and arrested everyone in sight.

This is where the common historical account differs from what family members who were there observed. The Sieben family member story is as follows, despite what was reported in the newspapers at the time. The transfer of funds either happened at another time or in another place. The raid happened about a week after this transaction. Also, O´Banion had no idea when a raid would take place, he only knew that the police officer he was paying off to inform him of when the next inspection was going to happen was no longer in a position to tell him. Elliot Ness had figured the cop for a “dirty” cop and had him transferred to where we don´t know, just out of the picture.

The normal operation with the gangsters was to at all times have two gangsters on the premises to run things. One would work in the office and the other was one of the bartenders. When the raid DID happen, the gangster/bartender, ran back through the brewery and kicked out the operating engineer that was running the steam engine that was used for refrigeration. He then grabbed a pair of overalls and dirtied his face with coal dust and sat at the controls of the steam engine so it looked like he was just an “engineer” worker and not a gangster. The gangster in the office came out and saw that there was a police officer standing guard in the street in front of the brewery. He got Leonard Sieben (who was 8 years old at the time) and told him to go out front and stand next to the officer and act like he was pulling a handkerchief out of his sleeve when the officer looked the other way. That was the signal for the gangster to slip out the front door and down the street, unseen. When the rest of the police surrounded the building and came in to conduct the raid, they ran right past the “engineer” who then just walked out the back door.

No gangsters were arrested at that time, they must have been rounded up later and this fact was hidden in an apparently elaborate deception so that the public could not find out. One might suspect that Elliot Ness had to score some kind of hit to garner some public or political support at a time when it was widely known that Prohibition was not working. The court records make no mention of Torrio, O´banion or old Scarface himself. The only names mentioned are “a Mr. Sieben, who owns the Realty” and George Frank who was the lease operator.

No matter which version you want to believe, this is what led to the infamous “handshake murder” of O´Banion at his north side State Street flower shop. It was also what sparked off the north and south side gang wars, including the St. Valentine´s DayMassacre in 1929.

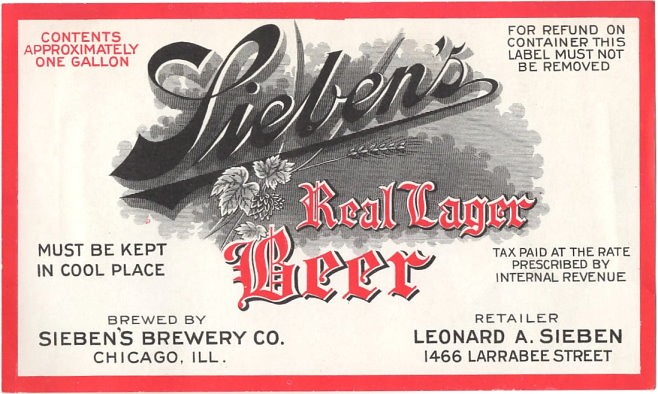

In 1933 Prohibition came to an end and the Sieben family reopened the brewery, bier stube and garden. For the next three and a half decades, Sieben´s Brewery Company would brew the fine beers for which it was known. In the 1950´s and 1960´s the beer business was changing and Sieben´s was finding it hard to keep up. Faced with the competition of mass produced beers, the Sieben´s Brewery and associated bier stube closed in 1967. The bottling house caught fire in 1968 and was heavily damaged. In 1969 all of the Sieben´s Brewery Company buildings were torn down.

In the 1980´s the name Sieben Brewery was resurrected by group of entrepreneurs not related to the Sieben family. The “new Sieben´s” was a brew pub in the River North Area of Chicago. The brew pub did not package and distribute their products, nor did they ever brew or have the original Sieben´s Brewery recipes.

In 2006 the Sieben´s family is back in the brewing business. Richard Sieben is a fourth generation family brewer and along with long time homebrewing friend Elliot Hamilton are, “Carrying on a Great Family Brewing Tradition.” Sieben´s brings back the original “Real Lager Beer” that was brewed at the original brewery. The Sieben´s name has been around since the time when Chicago was a big beer brewing town. That´s why we like to think and say that we´re also “Carrying on Chicago´s Great Brewing Tradition.”

Sieben’s beer, after a two year run on the market has been temporarily withdrawn from distribution. Not having our own brewery, while saving a bundle of money in infrastructure, costs us in flexibility. Our Wisconsin based brewery is ready and willing to produce more beer but until we are able to secure a dependable distributor who has our product featured in their portfolio, we must take time off to rethink our strategy.

This postcard of the Sieben Bier Strude is from 1937.

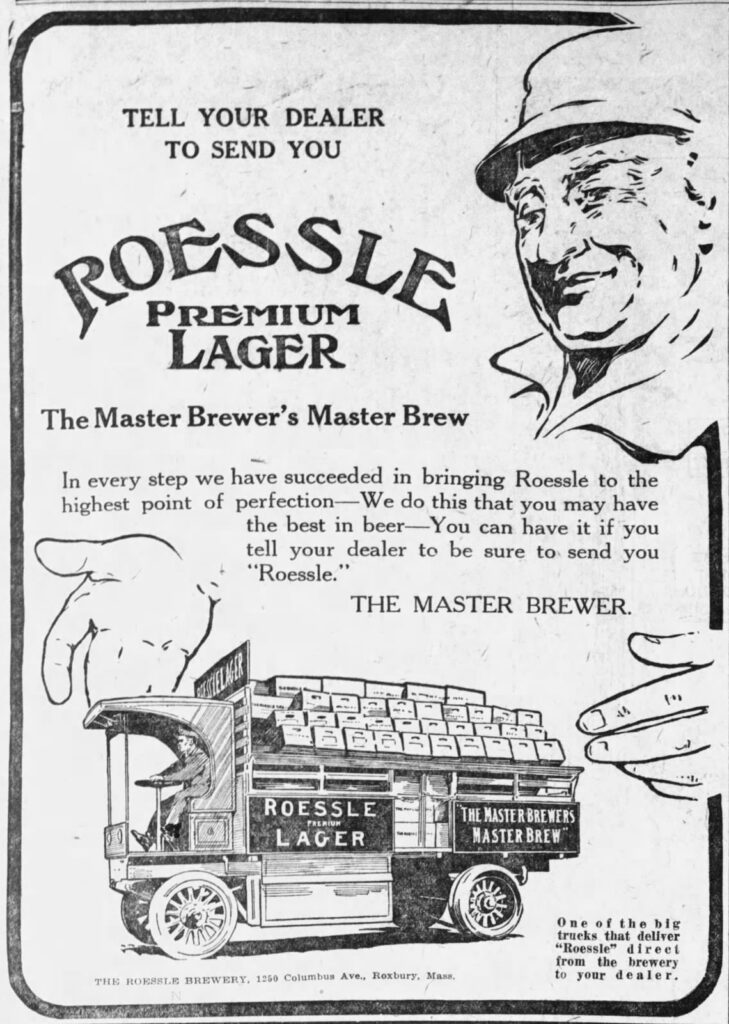

A brewery delivery truck around 1905.

A brewery delivery truck around 1905.

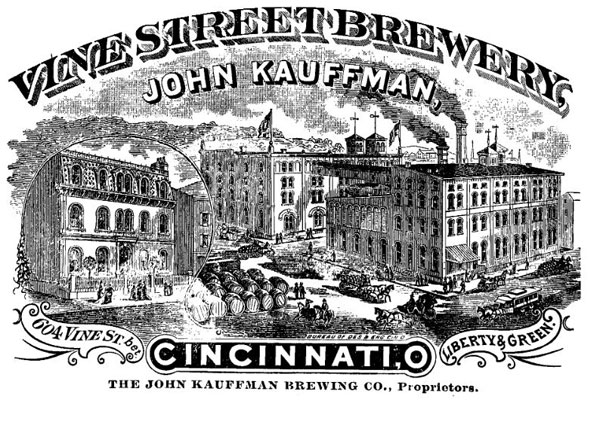

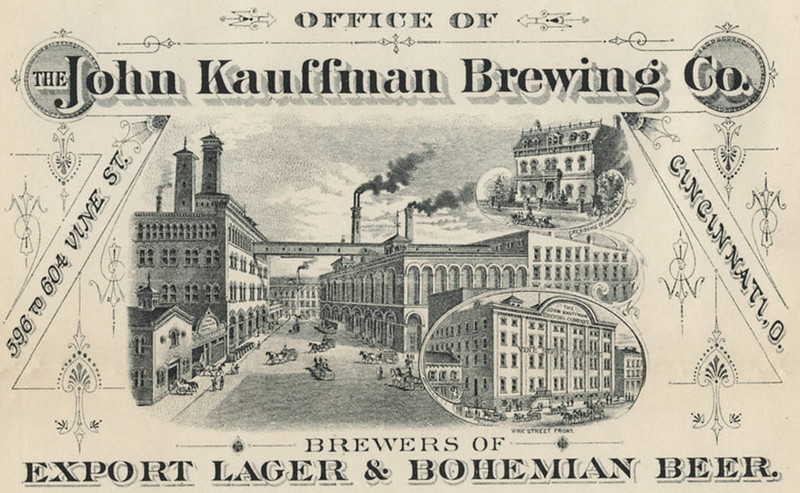

Here’s the letterhead from the John Kauffman Brewing Co.

Here’s the letterhead from the John Kauffman Brewing Co.