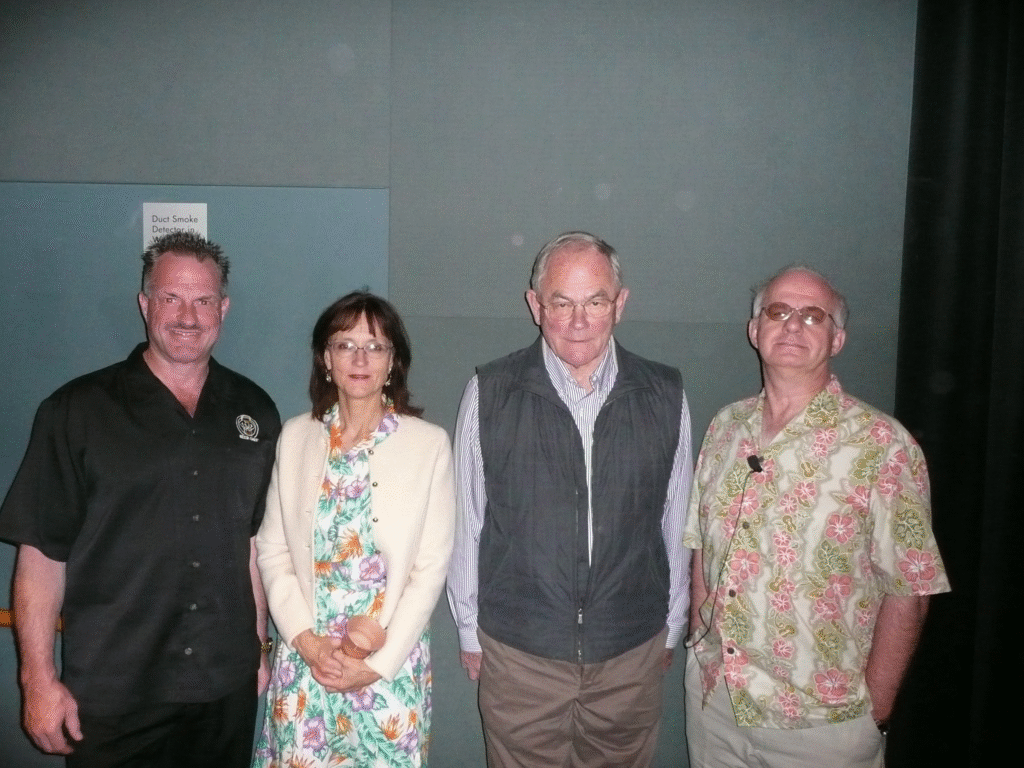

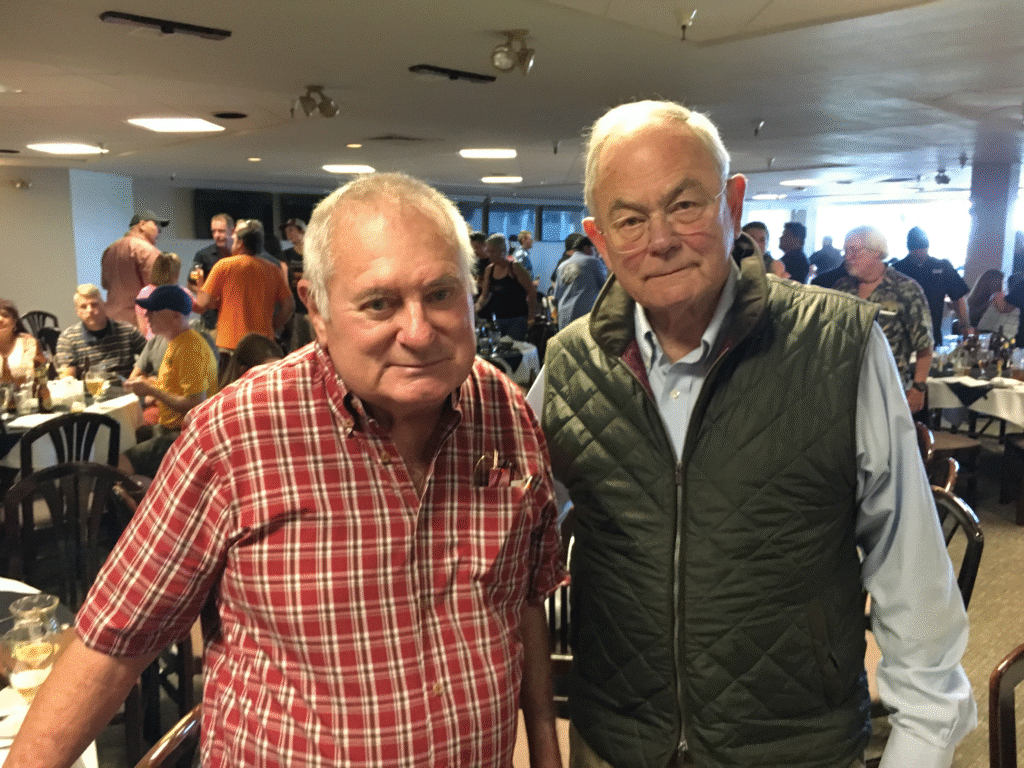

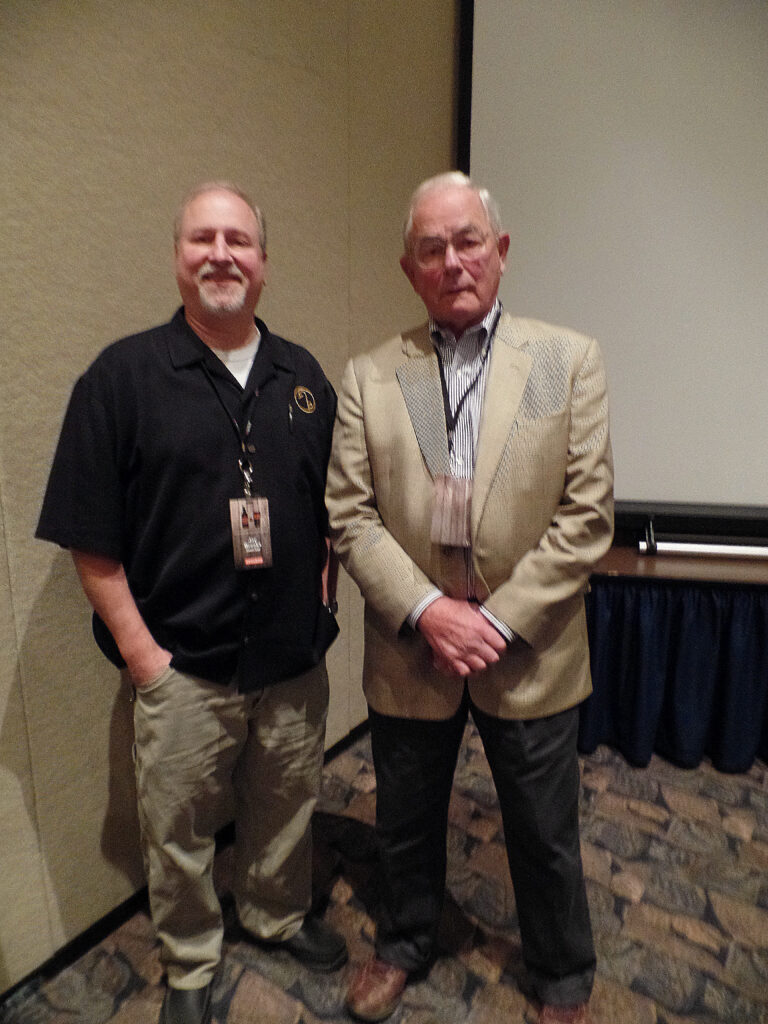

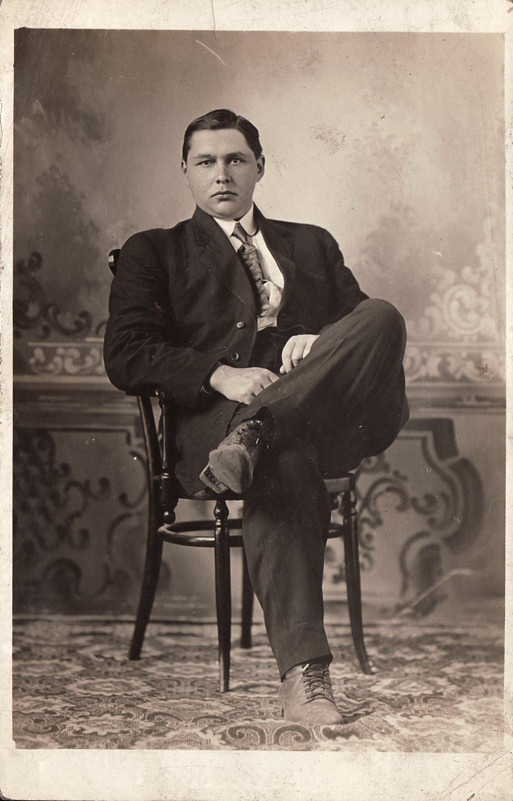

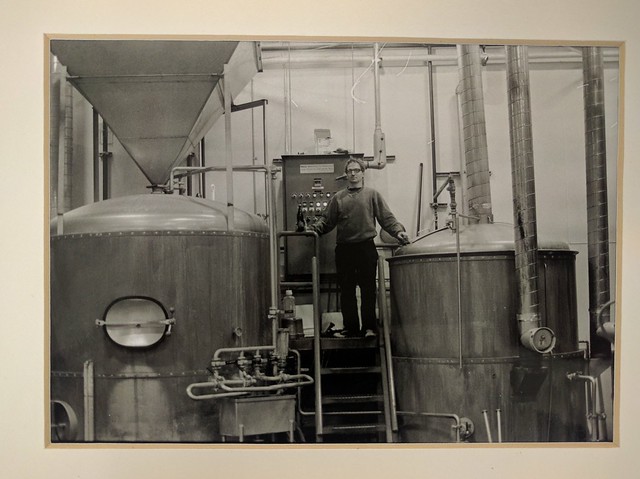

Fritz Maytag, who bought the failing Anchor Brewery in 1965 and turned it into a model for the microbrewery revolution, celebrates his 88th birthday today. It’s no stretch to call Fritz the father of craft beer, he introduced so many innovations that are common today and influenced countless brewers working today. A few years ago, Maytag sold Anchor Brewery and Distillery to Keith Greggor and Tony Foglio of the Griffin Group, and in 2017 acquired by Sapporo Breweries, then closed last year ago, but continued to make his York Creek wine and for a time consulted with Anchor as Chairman Emeritus. I was happy to see him again a few years ago, first at the California Beer Summit, and later when I was invited to introduce him to receive an award from the Northern California Brewers Guild in Sacramento, and more recently he unexpectedly showed up at the Anchor taproom the day before it closed last year. Join me in wishing Fritz a very happy birthday.