Today is the birthday of John Gorrie (October 3, 1803-June 29, 1855). He “was a physician, scientist, inventor, and humanitarian,” and most importantly, is credited with creating one of the very first refrigerators, an important development for the brewing industry.

Here’s one brief account, from a history of refrigeration on The Sun:

The man credited with developing the first actual “fridge” was an American doctor, John Gorrie, who built an ice-maker in 1844 based on Evans’ work of decades earlier. He also pioneered air conditioning at the same time, since his idea was to blow air across the ice-making machine to cool hospital patients suffering from malaria in Florida.

Gorrie did not make the fortune he deserved. His business partner died and his leaky machines were mocked by the Press and the ice-producing firms to whom he could have been a threat. He died sick and broke aged 51.

Here’s his story from his Wikipedia page:

Since it was necessary to transport ice by boat from the northern lakes, Gorrie experimented with making artificial ice.

After 1845, he gave up his medical practice to pursue refrigeration products. On May 6, 1851, Gorrie was granted Patent No. 8080 for a machine to make ice. The original model of this machine and the scientific articles he wrote are at the Smithsonian Institution. In 1835, patents for “Apparatus and means for producing ice and in cooling fluids” had been granted in England and Scotland to American-born inventor Jacob Perkins, who became known as “the father of the refrigerator.” Impoverished, Gorrie sought to raise money to manufacture his machine, but the venture failed when his partner died. Humiliated by criticism, financially ruined, and his health broken, Gorrie died in seclusion on June 29, 1855. He is buried in Magnolia Cemetery.

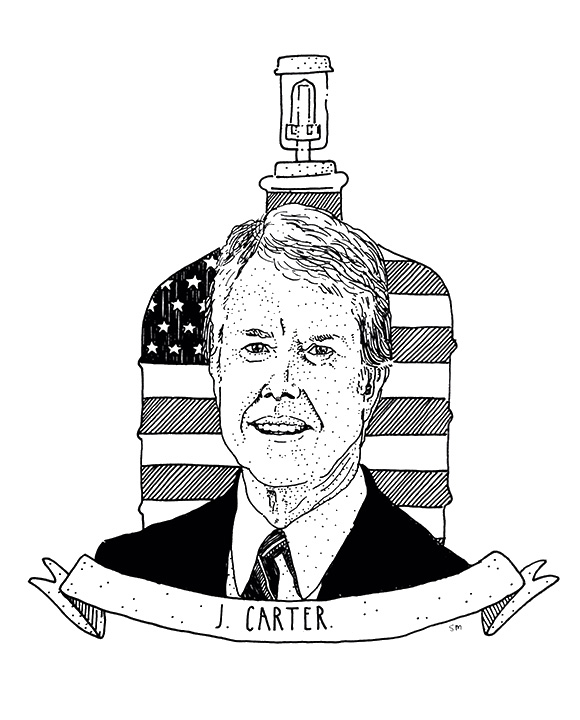

Another version of Gorrie’s “cooling system” was used when President James A. Garfield was dying in 1881. Naval engineers built a box filled with cloths that had been soaked in melted ice water. Then by allowing hot air to blow on the cloths it decreased the room temperature by 20 degrees Fahrenheit. The problem with this method was essentially the same problem Gorrie had. It required an enormous amount of ice to keep the room cooled continuously. Yet it was an important event in the history of air conditioning. It proved that Dr. Gorrie had the right idea, but was unable to capitalize on it. The first practical refrigeration system in 1854, patented in 1855, was built by James Harrison in Geelong, Australia.

And this account, entitled “Dr. John Gorrie, Refrigeration Pioneer,” is by George L. Chapel of the Apalachicola Area Historical Society in Apalachicola, Florida, which is the location of the John Gorrie State Museum:

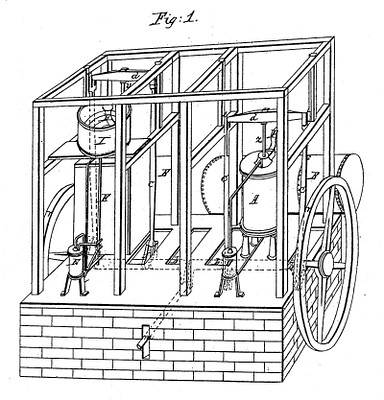

Dr. John Gorrie (1803 – 1855), an early pioneer in the invention of the artificial manufacture of ice, refrigeration, and air conditioning, was granted the first U.S. Patent for mechanical refrigeration in 1851. Dr. Gorrie’s basic principle is the one most often used in refrigeration today; namely, cooling caused by the rapid expansion of gases. Using two double acting force pumps he first condensed and then rarified air. His apparatus, initially designed to treat yellow fever patients, reduced the temperature of compressed air by interjecting a small amount of water into it. The compressed air was submerged in coils surrounded by a circulating bath of cooling water. He then allowed the interjected water to condense out in a holding tank, and released or rarified, the compressed air into a tank of lower pressure containing brine; This lowered the temperature of the brine to 26 degrees F. or below, and immersing drip-fed, brick-sized, oil coated metal containers of non-saline water, or rain water, into the brine, manufactured ice bricks. The cold air was released in an open system into the atmosphere.

The first known artificial refrigeration was scientifically demonstrated by William Cullen in a laboratory performance at the University of Glasgow in 1748, when he let ethyl ether boil into a vacuum. In 1805, Oliver Evans in the United States designed but never attempted to build, a refrigeration machine that used vapor instead of liquid. Using Evans’ refrigeration concept, Jacob Perkins of the U.S. and England, developed an experimental volatile liquid, closed-cycle compressor in 1834.

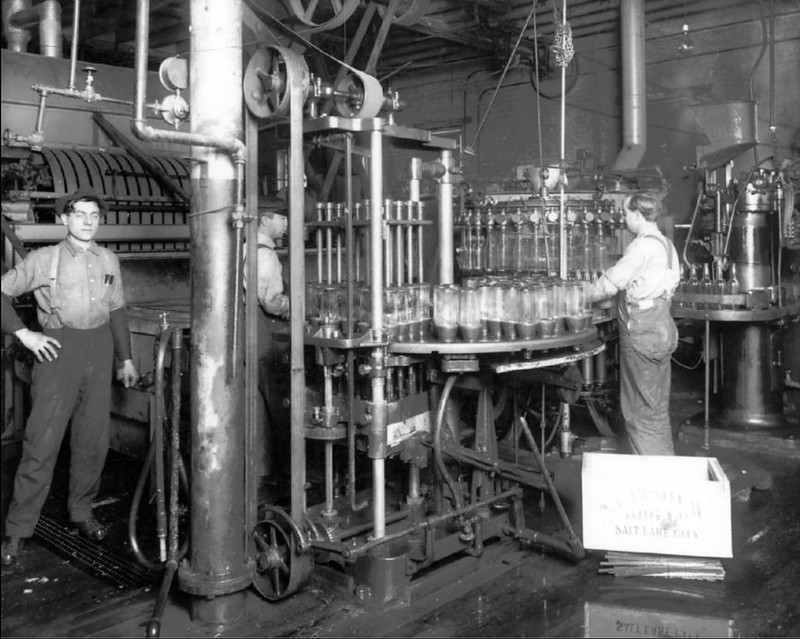

Commercial refrigeration is believed to have been initiated by an American businessman, Alexander C. Twinning using sulphuric ether in 1856. Shortly afterward, an Australian, James Harrison, examined the refrigerators used by Gorrie and Twinning, and introduced vapor (ether) compression refrigeration to the brewing and meat packing industries.

The granting of a U.S. Patent in 1860 to Ferdinand P.E. Carre of France, for his development of a closed, ammonia-absorption system, laid the foundation for widespread modern refrigeration. Unlike vapor-compression machines which used air, Carre used rapidly expanding ammonia which liquifies at a much lower temperature than water, and is thus able to absorb more heat. Carre’s refrigeration became, and still is, the most widely used method of cooling. The development of a number of synthetic refrigerants in the 1920’s, removed the need to be concerned about the toxic danger and odor of ammonia leaks.

The remaining problem for the development of modern air conditioning would not be that of lowering temperature by mechanical means, but that of controlling humidity. Although David Reid brought air into contact with a cold water spray in his modification of the heating and ventilating system of the British Parliament in 1836, and Charles Smyth experimented with air cycle cooling (1846 – 56), the problem was resolved by Willis Haviland Carrier’s U.S. Patent in 1906, in which he passed hot soggy air through a fine spray of water, condensing moisture on the droplets, leaving drier air behind. These inventions have had global implications.

Dr. Gorrie was honored by Florida, when his statue was placed in Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol. In 1899, a monument to Dr. Gorrie was erected by the Southern Ice Exchange in the small coastal town of Apalachicola, where he had served as mayor in 1837, and had developed his machine.

Reportedly born October 3, 1803 in Charleston, South Carolina, of Scots – Irish descent, he was raised in Columbia, S.C. He attended the College of Physicians and Surgeons of the Western District of New York, in Fairfield, New York, from 1825 to 1827. Although the school lasted only a few decades, it had a profound influence, second only to the Philadelphia Medical School, upon the scientific and medical community of the United States in the 19th century. Young Asa Gray, from Oneida County, New York, who by 1848 would be ranked as the leading botanist in the United States, and who in time would become a close friend of Dr. Alvin Wentworth Chapman of Apalachicola, the leading botanist in the South, served as an assistant in the school’s chemical department. In later years, Dr. Gray had distinct recollections of Gorrie as a “promising student.”

Dr. Gorrie initially practiced in Abbeville, South Carolina, in 1828, coming to the burgeoning cotton port of Apalachicola in 1833. He supplemented his income by becoming Assistant (1834), then Postmaster in Apalachicola. He became a Notary Public in 1835. The Apalachicola Land Company obtained clear title to the area by a U.S. Supreme Court decision in 1835, and in 1836 laid out the city’s grid-iron plat along the lines of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Gorrie, who served as Vice-Intendant in 1836, and Intendant (Mayor), in 1837, would be an effective advocate for the rest of his life for draining the swamps, clearing the weeds and maintaining clean food markets in the city. He first served as Secretary of the Masonic Lodge in 1835, was a partner in the Mansion House Hotel (1836), President of the Apalachicola Branch Bank of Pensacola (1836), a charter member of the Marine Insurance Bank of Apalachicola (1837), a physician for the Marine Hospital Service of the U.S. Treasury Department (1837 – 1844), and a charter incorporator and founding vestryman of Trinity Episcopal Church, Apalachicola (1837).

Dr. Gorrie married Caroline Frances Myrick Beman, of a Columbia, South Carolina family, the widowed proprietress of the Florida Hotel in Apalachicola, on May 8, 1838. Shortly thereafter, he resigned his various positions in Apalachicola, and the family left the city not to return until 1840. He was named Justice of the Peace in 1841, the same year that yellow fever struck the area.

Mal-aria, Italian, “bad air”, and yellow fever, prevailed in the hot, low-lying, tropical and sub-tropical areas where there was high humidity and rapid decomposition of vegetation. Noxious effluvium, or poisonous marsh gas was thought to be the cause. The “putrid” winds from marshy lowlands were regarded as deadly, especially at night. The specific causes were unknown, and although one had quinine for malaria, the gin and tonic of India, there was no cure nor preventive vaccine, for yellow fever. The legendary Flying Dutchman was founded on the story of a ship with yellow fever onboard.

Malaria would start with shaking and violent chills, followed by high fever, and a drenching sweat. Insidious, it could recur in the victim as well as kill. Yellow fever did not recur; one either died or survived. It came in mysterious, vicious waves, killing anywhere from 12 to 70 percent of its victims. It started with shivering, high fever, insatiable thirst, savage headaches, and severe back and leg pains. In a day or so, the restless patient would become jaundiced and turn yellow. In the terminal stages, the patient would spit up mouthfuls of dark blood, the terrifying “black vomit” (vomito negro), the body temperature would drop, the pulse fade, and the comatose patient, cold to the touch, would die in about 8 to 10 hours. So great was the terror, that the victims would be buried as quickly as possible. Areas would be quarantined, and yellow flags flown. Gauze would be hung over beds to filter air; handkerchiefs would be soaked in vinegar; garlic would be worn in shoes. Bed linens and compresses would be soaked in camphor; sulfur would be burned in outdoor smudge pots. Gunpowder would be burned, and cannons would be fired. And, later, when it was over, the cleaning and fumigating would occur.

It would not be until 1901 in Havana, Cuba, that Drs. Walter Reed, Carlos Finlay and William Crawford Gorgas, with others, would demonstrate conclusively that the Aedes Aegypti, or Stegomyia Fasciata mosquito was the carrier of the yellow fever virus. It would be about the same time that the English physician, Sir Ronald Ross in India, would correctly identify the Anopheles mosquito as the carrier of the malaria protozoa. As early as 1848, in Mobile, Alabama, however, Dr. Josiah Nott first suggested that mosquitos might be involved. The yellow fever epidemic of 1841, and the hurricane and tidal wave, known locally as the “Great Tide” of 1842, destroyed Apalachicola’s rival cotton port of St. Joseph some thirty miles to the west on the deep water sound of St. Joseph’s Bay. Using Florida’s first railway (1837) to transport cotton from the Apalachicola River, St. Joseph had hosted Florida’s Constitutional Convention in 1838.

Dr. Gorrie became convinced that cold was the healer. He noted that “Nature would terminate the fevers by changing the seasons.” Ice, cut in the winter in northern lakes, stored in underground ice houses, and shipped, packed in sawdust, around the Florida Keys by sailing vessel, in mid-summer could be purchased dockside on the Gulf Coast. In 1844, he began to write a series of articles in Apalachicola’s “Commercial Advertiser” newspaper, entitled, “On the prevention of Malarial Diseases”.

He used the Nom De Plume, “Jenner”, a tribute to Edward Jenner, (1749 – 1823), the discoverer of smallpox vaccine. According to these articles, he had constructed an imperfect refrigeration machine by May, 1844, carrying out a proposal he had advanced in 1842. All of Gorrie’s personal records were accidentally destroyed sometime around 1860.

“If the air were highly compressed, it would heat up by the energy of compression. If this compressed air were run through metal pipes cooled with water, and if this air cooled to the water temperature was expanded down to atmospheric pressure again, very low temperatures could be obtained, even low enough to freeze water in pans in a refrigerator box.” The compressor could be powered by horse, water, wind driven sails, or steampower.

Dr. Gorrie submitted his patent petition on February 27, 1848, three years after Florida became a state. In April of 1848, he was having one of his ice machines built in Cincinnati, Ohio, at the Cincinnati Iron Works, and in Octobcr, he demonstrated its operation. It was described in the Scientific American in September of 1849. On August 22, 1850, he received London Patent #13,124, and on May 6, 1851, U. S. Patent #8080. Although the mechanism produced ice in quantities, leakage and irregular performance sometimes impaired its operation. Gorrie went to New Orleans in search of venture capital to market the device, but either problems in product demand and operation, or the opposition of the ice lobby, discouraged backers. He never realized any return from his invention. Upon his death on June 29, 1855, he was survived by his wife Caroline (1805 – 1864), his son John Myrick (1838 – 1866), and his daughter, Sarah (1844 – 1908). Dr. Gorrie is buried in Gorrie Square in Apalachicola, his wife and son are buried-St. Luke’s-Episcopal Cemetery, Marianna, Florida, and his daughter, in Milton, Florida.