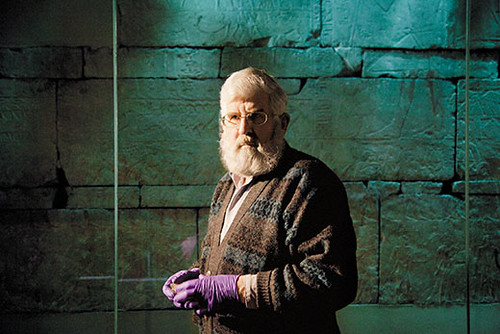

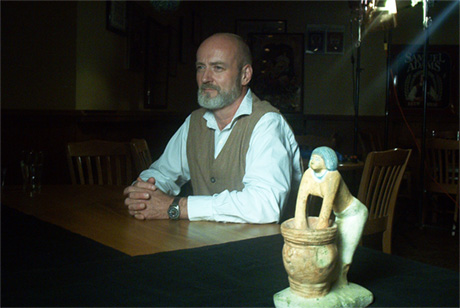

Today is the birthday of Alan D. Eames (April 16, 1947-February 10, 2007). Eames was an anthropologist of beer and a writer, and was known as both the “Indiana Jones of Beer” and “The Beer King.”

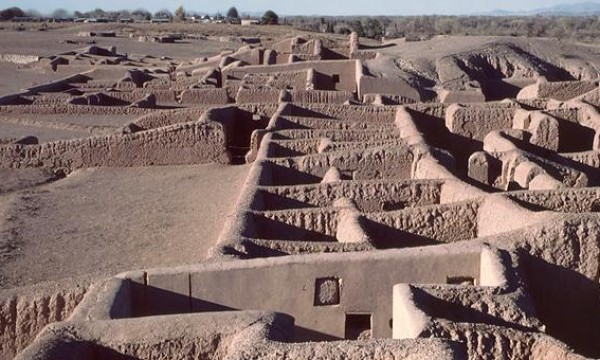

Eames acquired a reputation as the “Indiana Jones of beer” in reference to his global quest to learn about the origins of beer and the role it played in ancient societies and cultures. Eames visited 44 countries. In Egypt he found hieroglyphics about beer, and travelled on the Amazon River in search of a lost black brew. In the Andes, Eames trekked in search of a brew made from strawberries that were the size of baseballs.

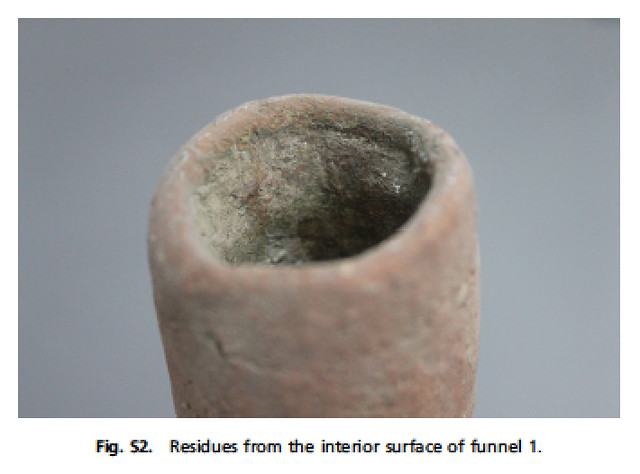

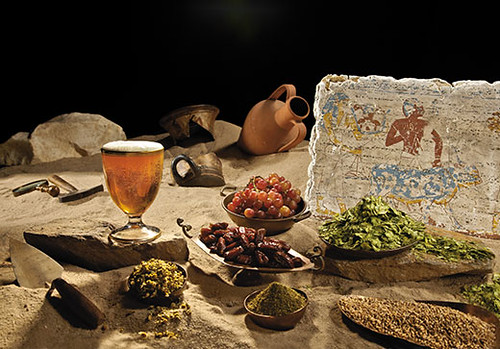

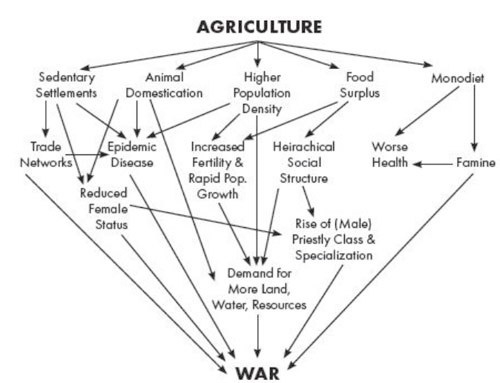

Eames claimed to have found the world’s “oldest beer advertisement” on a Mesopotamian stone tablet that dated to roughly 4000 B.C.[1] The tablet depicted a headless woman with large breasts holding goblets of beer in each of her hands. Eames claimed that the tagline to the tablet was “Drink Elba, the beer with the heart of a lion.” Eames believed that beer was the most feminine of drinks, and thought that ancient societies considered it a gift from a goddess rather than a god, as from the gods Ama-Gestin and Ninkasis. With Professor Solomon Katz of the University of Pennsylvania, Eames formulated the theory that beer was an important factor in the creation of settled and civilised societies.

Here’s Eames’ obituary from the New York Times:

Alan D. Eames, who cultivated his reputation as “the Indiana Jones of beer” by crawling into Egyptian tombs to read hieroglyphics about beer and voyaging along the Amazon in search of a mysterious lost black brew, died on Feb. 10 at his home in Dummerston, Vt. He was 59.

His wife, Sheila, said he died after suffering respiratory failure while he slept.

Mr. Eames called himself a beer anthropologist, a role that allowed him to expound on subjects like what he put forward as the world’s oldest beer advertisement, dating to roughly 4000 B.C.

In it a Mesopotamian stone tablet depicted a headless woman with enormous breasts holding goblets of beer in each hand. The tagline, at least in his interpretation, was: “Drink Elba, the beer with the heart of a lion.”

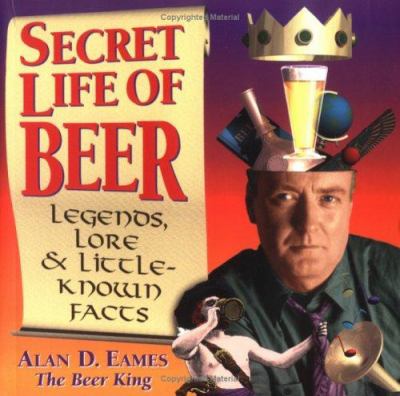

He explored similar topics in seven books, the best known of which was “The Secret Life of Beer” (1995), in myriad radio and television appearances and in speeches at colleges and other institutions. A typical title: “Beer: A Gift from God, or the Devil’s Training Wheels.”

Mr. Eames, who followed the golden liquid to 44 countries, often told about his perilous trek high in the Andes in pursuit of an ancient brew made from strawberries the size of baseballs. Or about Aztecs forbidding drunkenness except among those 52 years of age or older. Or about accounts that said Norse ale was served with garlic to ward off evil.

Mr. Eames’s favorite and perhaps most startling message was that beer is the most feminine of beverages. He said that in almost all ancient societies beer was considered a gift from a goddess, never a male god. Most often, women began the brewing process by chewing grains and spitting them into a pot to form a fermentable mass.

Alan Duane Eames was born on April 16, 1947, in Gardner, Mass. His father was Warren Baker Eames, a Harvard-trained anthropologist. By the time he was 11, young Alan was advertising his magic act. He graduated from Mark Hopkins College in Brattleboro, Vt., now closed.

In 1968, he moved to New York City and opened an art gallery. He spent evenings at the New York Public Library researching beer.

His beer-related business ventures began in the mid-1970s with his acquisition of Gleason’s Package Store in Templeton, Mass., which became known for its large beer selection. He conceived, designed and operated Three Dollar Dewey’s Ale House in Portland, Me., and another with the same name in Brattleboro.

He found ways to cash in on his celebrity, including helping market Guinness stout. In an interview with The St. Petersburg Times, he lauded its “rich dark color, the creamy white head that leaves delicate traces of foamy lace on the inside of the glass.”

He concluded, “It is one of the great joys in this vale of tears.”

Mr. Eames was the founding director of the American Museum of Brewing History and Fine Arts in Fort Mitchell, Ky., known for its festive “beer camps.” He contributed items on subjects from ancient times to the mid-19th century to the Encyclopedia of Beer.

But beer did not always pay expenses, and Mr. Eames sometimes had to take jobs like packing boxes in a vitamin factory and tending bar.

Mr. Eames is survived by his fourth wife, the former Sheila Momaney; his sons, Adrian and Andrew, both of Dummerston; his daughter, Elena Eames of Brattleboro; his stepsons Logan and Riley Johnson, of Dummerston; his father, of East Templeton, Mass., and York Beach, Me.; his mother, Mavis Franks of Denham Springs, La.; his sister, Holiday Eames of Westminster, Vt.; his half-brother, Mark Warner of Baton Rouge, La., and one grandson.

There’s also obits from the UK Guardian and Real Beer.

Beer loses its historian

Above all others, Alan Eames loved Guinness. But after traveling the world to find new beers, it seemed too easy to love such a common one. He had another favorite, though: Fruitillata, a milkshake-like beer made with strawberries and corn, brewed only 10 days a year by a tribe in remote South American mountains. One year, he just happened to show up in time for a drink. But then, that was what Eames did.

Eames, a beer historian nicknamed the “Indiana Jones of Beer,” died in his sleep on February 10. He was 59. His career took him across the world, researching beers and the innumerable ways they’re made, and he wrote his findings in books such as Secret Life of Beer.

“He was very passionate about things, and he would develop intense interest in things,” said his wife, Sheila, who was living with Eames in Dummerston, VT. “There’s so much history in beer that he never grew tired of learning about it, reading about it, talking about it.”

She said his introduction to beer came at a beach party in Maine when he was 17.

It was a Ballantine IPA. “He wrote about the attraction of the green of the bottle, the perfect fit in the hand, the wonderful smack of it when the beer hit his tongue,” Sheila says. “He was always interested in history, but I think that was his first real life-changing event, as far as beer went.”

- Ale Dreams

- The Secret Life of Beer!: Exposed: Legends, Lore & Little-Known Facts

- A Beer Drinker’s Companion (5000 years of quotes & anecdotes about beer)

And here’s an interview of Eames by Robert Lauriston, though I’m not sure when it took place. You can also listen to him on the Splendid Table program, from a show recorded February 12, 2000.

I remember when he passed away, and even wrote a blog post about him. I only met Eames once, but we spoke on the phone a couple of times. But by a weird quirk of coincidence, I ended up with several boxes of miscellaneous stuff that Pete Slosberg bought. The books in his collection were donated to UC Davis (I think) but the leftover papers, press releases and other oddball stuff ended up in my garage after Pete and Amy moved to a smaller apartment in San Francisco. But there was some pretty interesting stuff among the boxes.