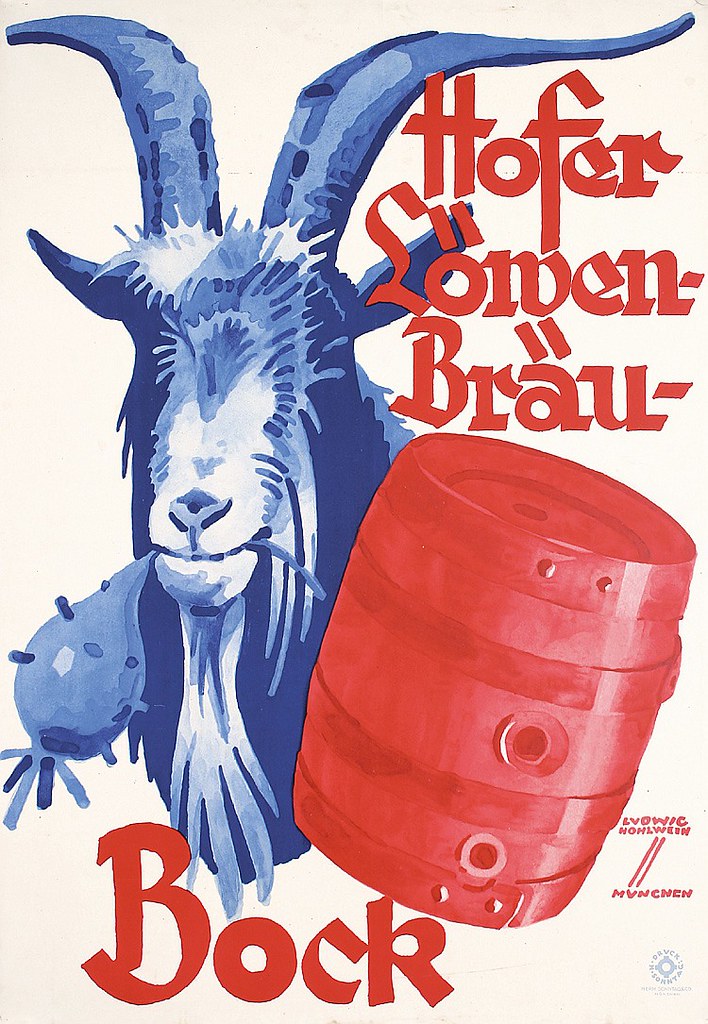

Friday’s ad is for Hofbräuhaus Mai:Bock, from 1913, I think. From the late 1800s until the 1940s, poster art really came into its own, and in Europe a lot of really cool posters, many of them for breweries, were produced. This poster is for Hofbräuhaus Mai:Bock, brewed by Hofbräu München, and was created by Hans Heinrich Koch in 1913.

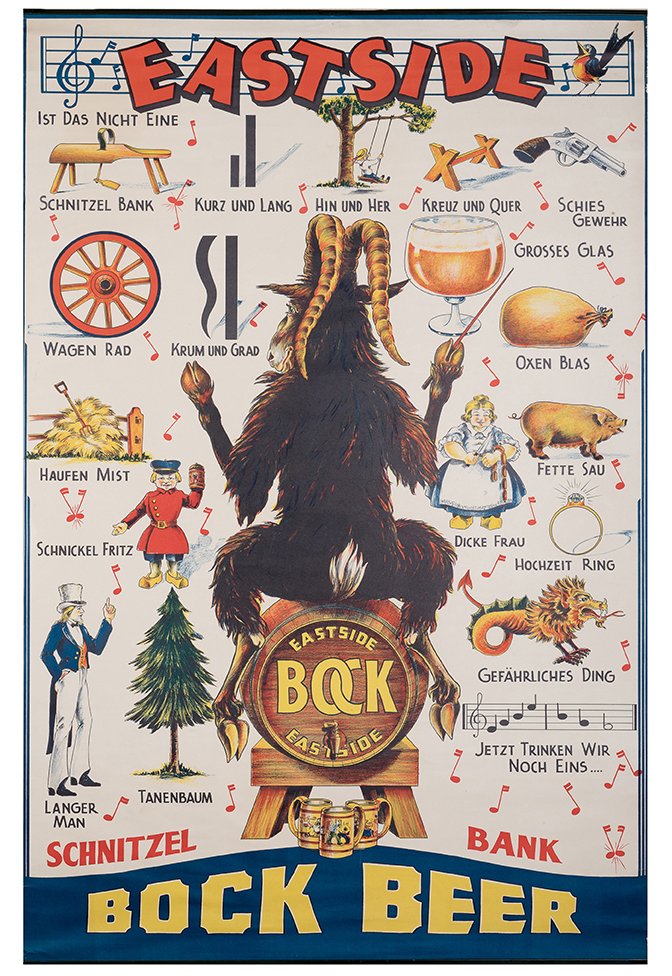

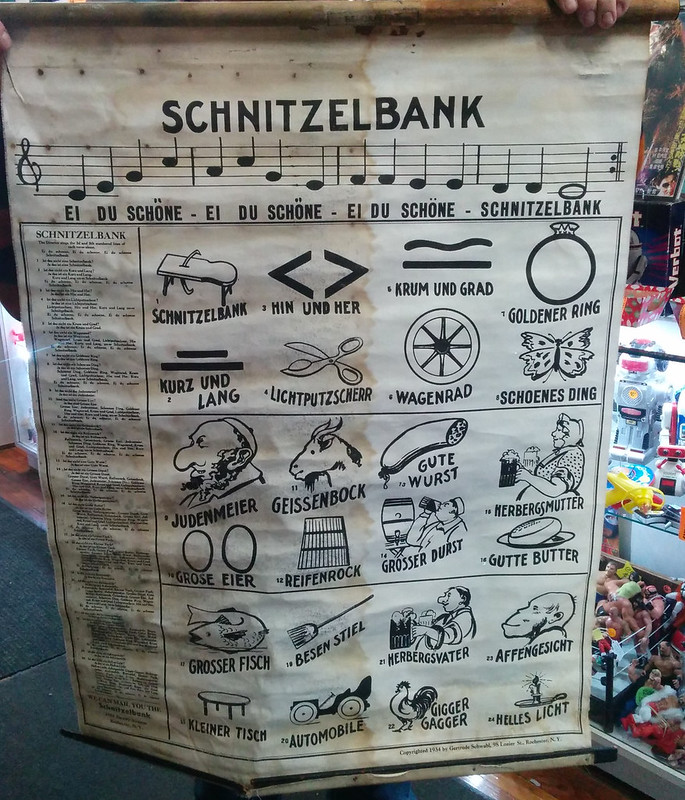

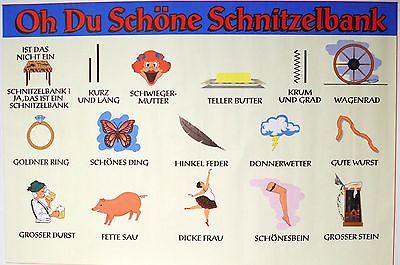

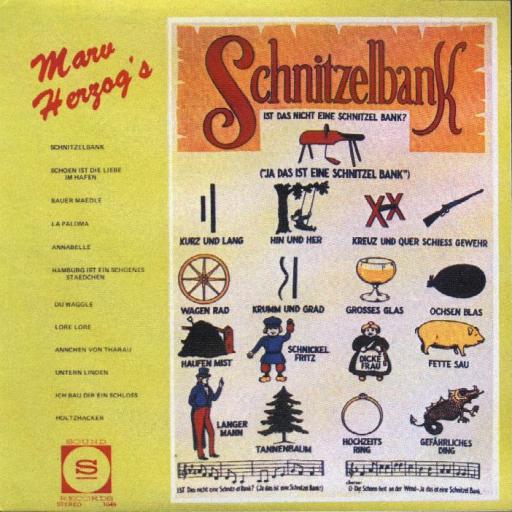

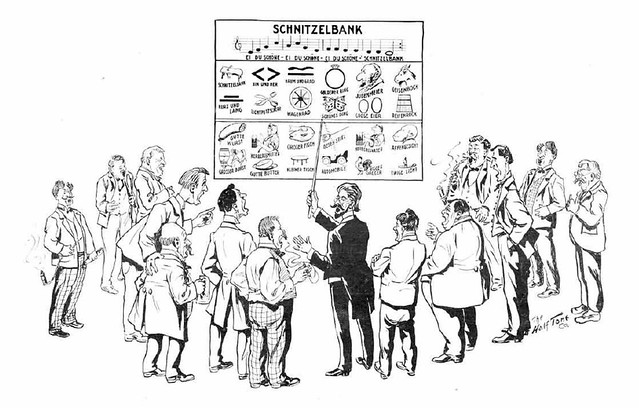

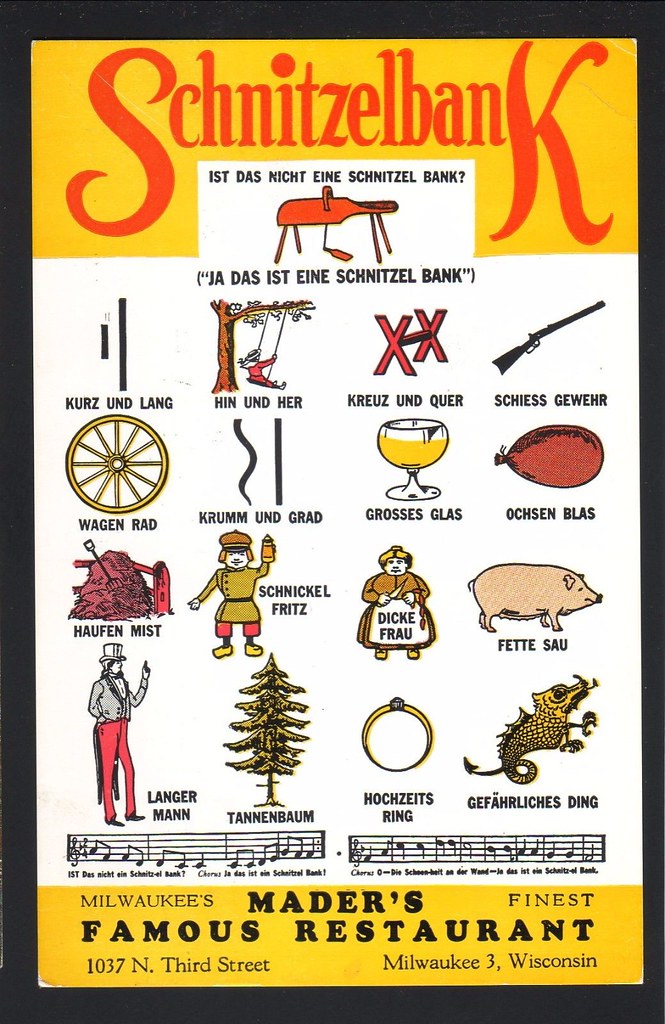

From Mader’s Famous Restaurant in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

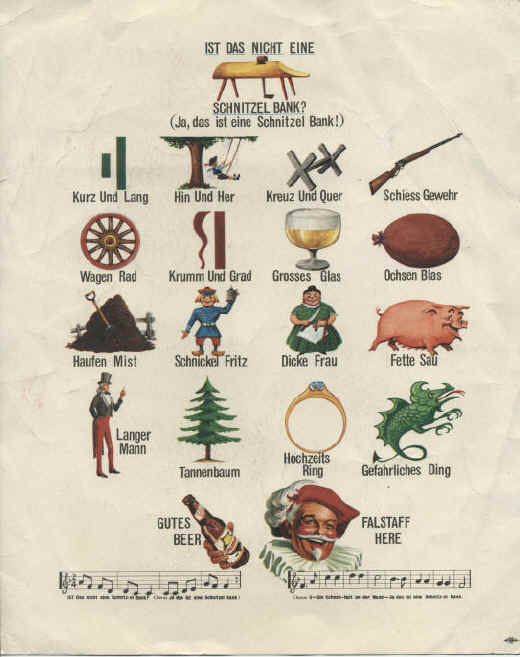

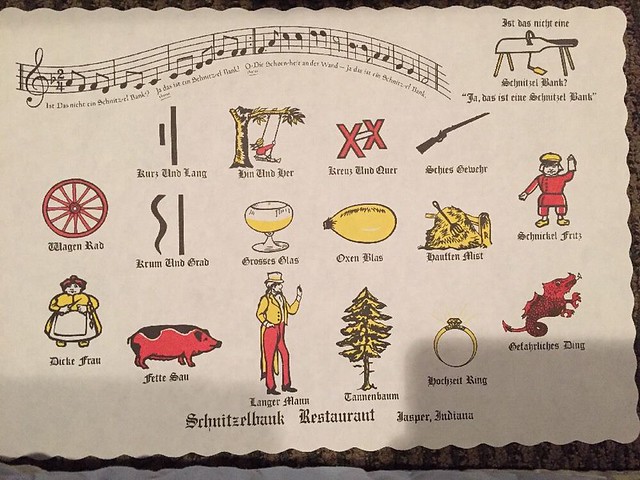

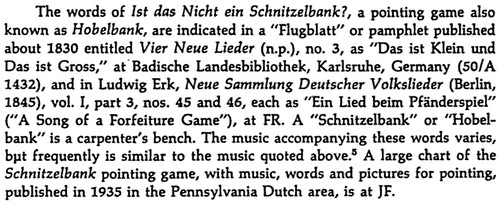

From Mader’s Famous Restaurant in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.