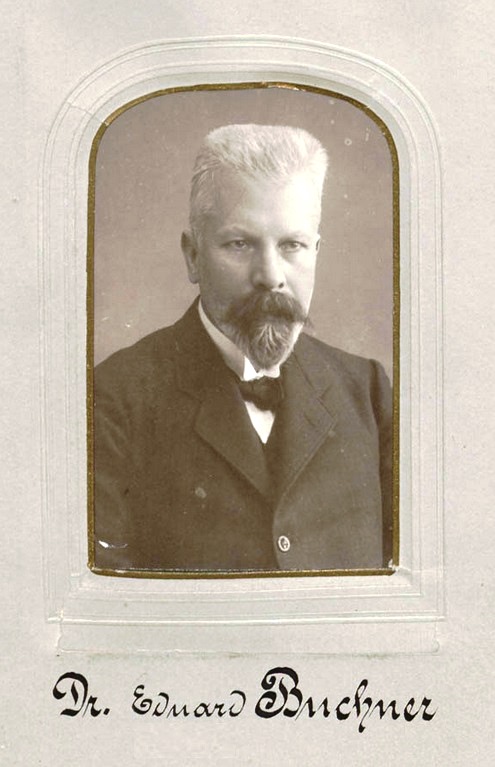

Today is the birthday of Eduard Buchner (May 20, 1860-August 13, 1917). Buchner was a German chemist and zymologist, and was awarded with Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1907 for his work on fermentation.

This is a short biography from The Famous People:

Born into an educationally distinguished family, Buchner lost his father when he was barely eleven years old. His elder brother, Hans Buchner, helped him to get good education. However, financial crisis forced Eduard to give up his studies for a temporary phase and he spent this period working in preserving and canning factory. Later, he resumed his education under well-known scientists and very soon received his doctorate degree. He then began working on chemical fermentation. However, his experience at the canning factory did not really go waste. Many years later while working with his brother at the Hygiene Institute at Munich he remembered how juices were preserved by adding sugar to it and so to preserve the protein extract from the yeast cells, he added a concentrated doze of sucrose to it. What followed is history. Sugar in the presence of enzymes in the yeast broke into carbon dioxide and alcohol. Later he identified the enzyme as zymase. This chance discovery not only brought him Nobel Prize in Chemistry, but also brought about a revolution in the field of biochemistry.

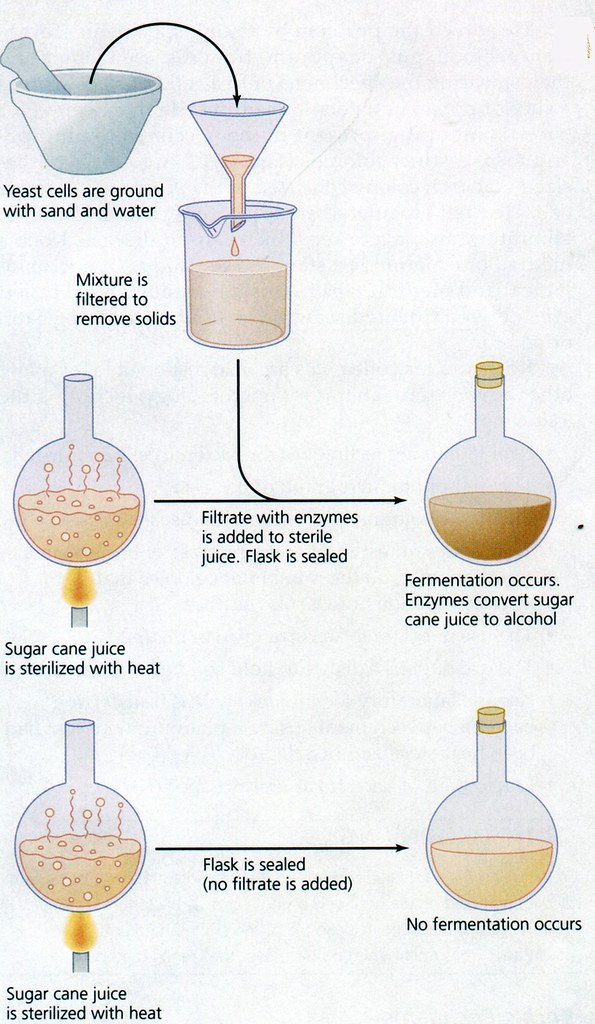

Eduard Buchner is best remembered for his discovery of zymase, an enzyme mixture that promotes cell free fermentation. However, it was a chance discovery. He was then working in his brother’s laboratory in Munich trying to produce yeast cell free extracts, which the latter wanted to use in an application for immunology.

To preserve the protein in the yeast cells, Eduard Buchner added concentrated sucrose to it. Bubbles began to form soon enough. He realized that presence of enzymes in the yeast has broken down sugar into alcohol and carbon dioxide. Later, he identified this enzyme as zymase and showed that it can be extracted from yeast cells. This single discovery laid the foundation of modern biochemistry.

One of the most important aspects of his discovery proving that extracts from yeast cells could elicit fermentation is that it “contradicted a claim by Louis Pasteur that fermentation was an ‘expression of life’ and could occur only in living cells. Pasteur’s claim had put a decades-long brake on progress in fermentation research, according to an introductory speech at Buchner’s Nobel presentation. With Buchner’s results, “hitherto inaccessible territories have now been brought into the field of chemical research, and vast new prospects have been opened up to chemical science.”

In his studies, Buchner gathered liquid from crushed yeast cells. Then he demonstrated that components of the liquid, which he referred to as “zymases,” could independently produce alcohol in the presence of sugar. “Careful investigations have shown that the formation of carbon dioxide is accompanied by that of alcohol, and indeed in just the same proportions as in fermentation with live yeast,” Buchner noted in his Nobel speech.

This is a fuller biography from the Nobel Prize organization:

Eduard Buchner was born in Munich on May 20, 1860, the son of Dr. Ernst Buchner, Professor Extraordinary of Forensic Medicine and physician at the University, and Friederike née Martin.

He was originally destined for a commercial career but, after the early death of his father in 1872, his older brother Hans, ten years his senior, made it possible for him to take a more general education. He matriculated at the Grammar School in his birth-place and after a short period of study at the Munich Polytechnic in the chemical laboratory of E. Erlenmeyer senior, he started work in a preserve and canning factory, with which he later moved to Mombach on Mainz.

The problems of chemistry had greatly attracted him at the Polytechnic and in 1884 he turned afresh to new studies in pure science, mainly in chemistry with Adolf von Baeyer and in botany with Professor C. von Naegeli at the Botanic Institute, Munich.

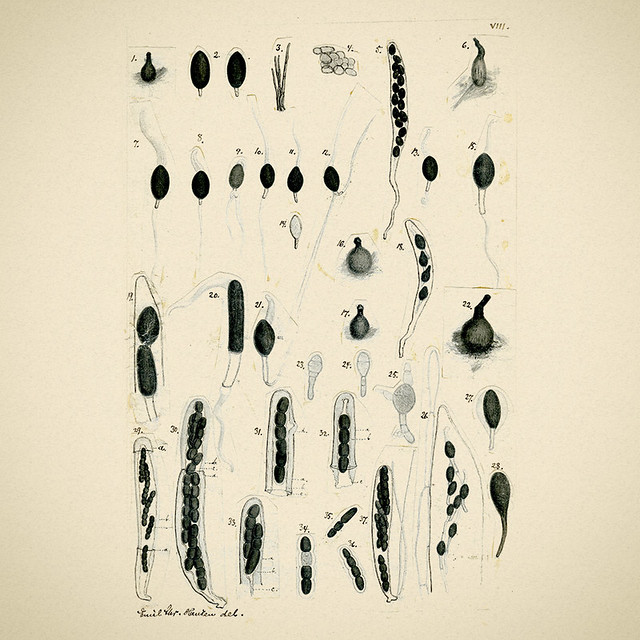

It was at the latter, where he studied under the special supervision of his brother Hans (who later became well-known as a bacteriologist), that his first publication, Der Einfluss des Sauerstoffs auf Gärungen (The influence of oxygen on fermentations) saw the light in 1885. In the course of his research in organic chemistry he received special assistance and stimulation from T. Curtius and H. von Pechmann, who were assistants in the laboratory in those days.

The Lamont Scholarship awarded by the Philosophical Faculty for three years made it possible for him to continue his studies.

After one term in Erlangen in the laboratory of Otto Fischer, where meanwhile Curtius had been appointed director of the analytical department, he took his doctor’s degree in the University of Munich in 1888. The following year saw his appointment as Assistant Lecturer in the organic laboratory of A. von Baeyer, and in 1891 Lecturer at the University.

By means of a special monetary grant from von Baeyer, it was possible for Buchner to establish a small laboratory for the chemistry of fermentation and to give lectures and perform experiments on chemical fermentations. In 1893 the first experiments were made on the rupture of yeast cells; but because the Board of the Laboratory was of the opinion that “nothing will be achieved by this” – the grinding of the yeast cells had already been described during the past 40 years, which latter statement was confirmed by accurate study of the literature – the studies on the contents of yeast cells were set aside for three years.

In the autumn of 1893 Buchner took over the supervision of the analytical department in T. Curtius’ laboratory in the University of Kiel and established himself there, being granted the title of Professor in 1895.

In 1896 he was called as Professor Extraordinary for Analytical and Pharmaceutical Chemistry in the chemical laboratory of H. von Pechmann at the University of Tübingen.

During the autumn vacation in the same year his researches into the contents of the yeast cell were successfully recommenced in the Hygienic Institute in Munich, where his brother was on the Board of Directors. He was now able to work on a larger scale as the necessary facilities and funds were available.

On January 9, 1897, it was possible to send his first paper, Über alkoholische Gärung ohne Hefezellen (On alcoholic fermentation without yeast cells), to the editors of the Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft.

In October, 1898, he was appointed to the Chair of General Chemistry in the Agricultural College in Berlin and he also held lectureships on agricultural chemistry and agricultural chemical experiments as well as on the fermentation questions of the sugar industry. In order to obtain adequate assistance for scientific research, and to be able to fully train his assistants himself, he became habilitated at the University of Berlin in 1900.

In 1909 he was transferred to the University of Breslau and from there, in 1911, to Würzburg. The results of Buchner’s discoveries on the alcoholic fermentation of sugar were set forth in the book Die Zymasegärung (Zymosis), 1903, in collaboration with his brother Professor Hans Buchner and Martin Hahn. He was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1907 for his biochemical investigations and his discovery of non-cellular fermentation.

Buchner married Lotte Stahl in 1900. When serving as a major in a field hospital at Folkschani in Roumania, he was wounded on August 3, 1917. Of these wounds received in action at the front, he died on the 13th of the same month.

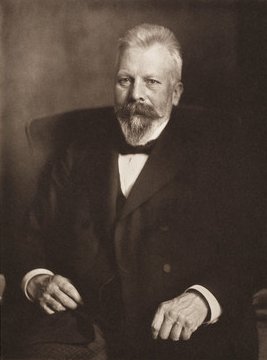

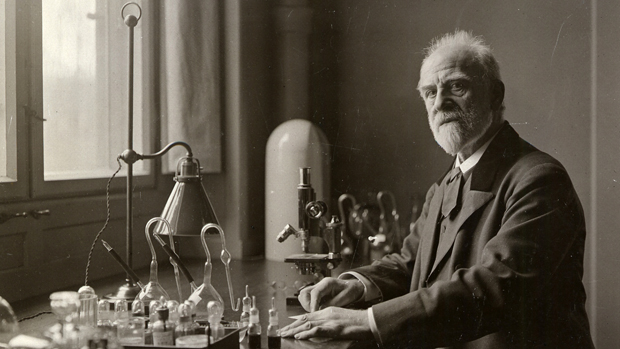

Emil Christian Hansen, taken in 1908, a year before his death.

Emil Christian Hansen, taken in 1908, a year before his death.