![]()

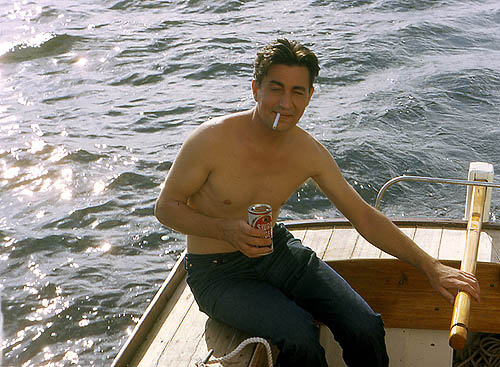

Today is the birthday of J.R.R. Tolkien, the English author of The Hobbit and the Lord of the Rings trilogy. But he was also a poet, which shouldn’t be a big surprise to fans since most of his works include pomes and songs as a part of his stories.

Tolkien was also a fan of British beer. One of the 30 Facts about J.R.R. Tolkien mentions his love of beer:

As a young student at Exeter college, Oxford University, he spent his first few years often getting into debt trying to keep up with richer students, who had more disposable income. Tolkien admits he had a great love of beer and talking into the early hours of the morning.

Author Eric San Juan also writes about J.R.R. Tolkien, Hobbits, and BEER. After detailing the ways in which beer influenced his life and work, he concludes that “yes, J.R.R. Tolkien enjoyed his beer, and this is reflected in his life’s work. He enjoyed quiet times and good conversation and a great pint. And who doesn’t?”

In 1968 during a BBC interview, part of a series entitled “In Their Own Words British Authors,” Tolkien quips. “I’m very fond of beer.” In fact, the interview is described as “John Izzard meets with JRR Tolkien at his home, walking with him through the Oxford locations that he loves while hearing the author’s own views about his wildly successful high-fantasy novels. Tolkien shares his love of nature and beer and his admiration for ‘trenchermen’ in this genial and affectionate programme.”

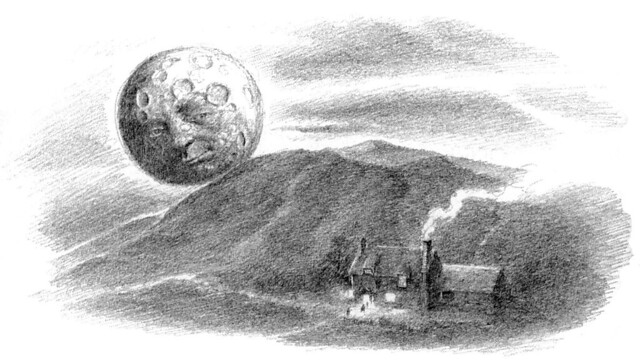

Earlier today, I tweeted a Tolkien quote, an excerpt from one of his poems. But while I’d collected the quote years ago, in checking it for accuracy, I encountered some confusion about the poem. It comes from a poem entitled “The Man in the Moon Stayed Up Too Late” from 1923 but some misattributed it to a later one, called “The Man in the Moon Came Down Too Soon,” which also appeared with the latter one in a collection published under the title “The Adventures of Tom Bombadil,” published in 1962.

The Man in the Moon Stayed Up Too Late also appeared in The Fellowship of the Ring, the first book in the Lord of the Rings trilogy.

In the Inn at Bree (“At the Sign of the Prancing Pony”, The Fellowship of the Ring Chapter 9) Frodo jumps on a table and recites “a ridiculous song” invented by Bilbo. “Here it is in full,” said Tolkien. “Only a few words of it are now, as a rule, remembered.”

There follows the tale, in thirteen ballad-like five-line stanzas, introducing each element in turn: “the Man in the Moon” himself, the ostler’s “tipsy cat/ that plays a five-stringed fiddle”, the little dog, the “hornéd cow” and the silver dishes and spoons.

Note that the cow is able to jump over the Moon with ease because the Man in the Moon has temporarily brought it down to Earth.

I read all of the books when I was younger — much younger — and I confess I didn’t recall the poem at all. Even when I found the quote, it was an excerpt. So today I figured I’d check out the full poem. The first one is great, filled with cool allusions, references to nursery rhymes, excellent wordplay and fun beeriness. The second doesn’t mention beer at all, only wine and moonshine, but it still interesting, especially as it’s considered a companion poem to the other. I’ve put both of them down below, with illustrations by British artist Alan Lee. Read the first one at least, it’s great — really great — but the second is nice, as well.

The Man in the Moon Stayed Up Too Late

There is an inn, a merry old inn

beneath an old grey hill,

And there they brew a beer so brown

That the Man in the Moon himself came down

one night to drink his fill.

The ostler has a tipsy cat

that plays a five-stringed fiddle;

And up and down he saws his bow

Now squeaking high, now purring low,

now sawing in the middle.

The landlord keeps a little dog

that is mighty fond of jokes;

When there’s good cheer among the guests,

He cocks an ear at all the jests

and laughs until he chokes.

They also keep a hornéd cow

as proud as any queen;

But music turns her head like ale,

And makes her wave her tufted tail

and dance upon the green.

And O! the rows of silver dishes

and the store of silver spoons!

For Sunday there’s a special pair,

And these they polish up with care

on Saturday afternoons.

The Man in the Moon was drinking deep,

and the cat began to wail;

A dish and a spoon on the table danced,

The cow in the garden madly pranced

and the little dog chased his tail.

The Man in the Moon took another mug,

and then rolled beneath his chair;

And there he dozed and dreamed of ale,

Till in the sky the stars were pale,

and dawn was in the air.

Then the ostler said to his tipsy cat:

‘The white horses of the Moon,

They neigh and champ their silver bits;

But their master’s been and drowned his wits,

and the Sun’ll be rising soon!’

So the cat on the fiddle played hey-diddle-diddle,

a jig that would wake the dead:

He squeaked and sawed and quickened the tune,

While the landlord shook the Man in the Moon:

‘It’s after three!’ he said.

They rolled the Man slowly up the hill

and bundled him into the Moon,

While his horses galloped up in rear,

And the cow came capering like a deer,

and a dish ran up with the spoon.

Now quicker the fiddle went deedle-dum-diddle;

the dog began to roar,

The cow and the horses stood on their heads;

The guests all bounded from their beds

and danced upon the floor.

With a ping and a pang the fiddle-strings broke!

the cow jumped over the Moon,

And the little dog laughed to see such fun,

And the Saturday dish went off at a run

with the silver Sunday spoon.

The round Moon rolled behind the hill,

as the Sun raised up her head.

She hardly believed her fiery eyes;

For though it was day, to her surprise

they all went back to bed!

The Man in the Moon Came Down Too Soon

The Man in the Moon had silver shoon,

It and his beard was of silver thread;

With opals crowned and pearls all bound

about his girdlestead,

In his mantle grey he walked one day

across a shining floor,

And with crystal key in secrecy

he opened an ivory door.

On a filigree stair of glimmering hair

then lightly down he went,

And merry was he at last to be free

on a mad adventure bent.

In diamonds white he had lost delight;

he was tired of his minaret

Of tall moonstone that towered alone

on a lunar mountain set.

Hĺ would dare any peril for ruby and beryl

to broider his pale attire,

For new diadems of lustrous gems,

emerald and sapphire.

So was lonely too with nothing to do

but stare at the world of gold

And heark to the hum that would distantly come

as gaily round it rolled.

At plenilune in his argent moon

in his heart he longed for Fire:

fot the limpid lights of wan selenites;

for red was his desire,

For crimson and rose and ember-glows,

for flame with burning tongue,

For the scarlet skies in a swift sunrise

when a stormy day is young.

He’d have seas of blues, and the living hues

of forest green and fen;

And he yearned for the mirth of the populous earth

and the sanguine blood of men.

He coveted song, and laughter long,

and viands hot, and wine,

Eating pearly cakes of light snowflakes

and drinking thin moonshine.

He twinkled his feet, as he thought of the meat,

of pepper, and punch galore;

And he tripped unaware on his slanting stair,

and like a meteor,

A star in flight, ere Yule one night

flickering down he fell

From his laddery path to a foaming bath

in the windy Bay of Bel.

He began to think, lest he melt and sink,

what in the moon to do,

When a fisherman’s boat found him far afloat

to the amazement of the crew,

Caught in their net all shimmering wet

in a phosphorescent sheen

Of bluey whites and opal lights

and delicate liquid green.

Against his wish with the morning fish

they packed him back to land:

‘You had best get a bed in an inn’, they said;

‘the town is near at hand’.

Only the knell of one slow bell

high in the Seaward Tower

Announced the news of his moonsick cruise.

Not a hearth was laid, not a breakfast made,

and dawn was cold and damp.

There were ashes for fire, and for grass the mire,

for the sun a smoking lamp

In a dim back-street. Not a man did he meet,

no voice was raised in song;

There were snores instead, for all folk were abed

and still would slumber long.

He knocked as he passed on doors locked fast,

and called and cried in vain,

Till he came to an inn that had light within,

and tapped at a window-pane.

A drowsy cook gave a surly look,

and ‘What do you want?’ said he.

‘I want fire and gold and songs of old

and red wine flowing free!’

‘You won’t get them here’, said the cook with a leer,

‘but you may come inside.

Silver I lack and silk to my back—

maybe I’ll let you bide’.

A silver gift the latch to lift,

a pearl to pass the door;

For a seat by the cook in the ingle-nook

it cost him twenty more.

For hunger or drouth naught passed his mouth

till he gave both crown and cloak;

And all that he got, in an earthen pot

broken and black with smoke,

Was porridge cold and two days old

to eat with a wooden spoon.

For puddings of Yule with plums, poor fool,

he arrived so much too sooo:

An unwary guest on a lunatic quest

from the Mountains of the Moon.