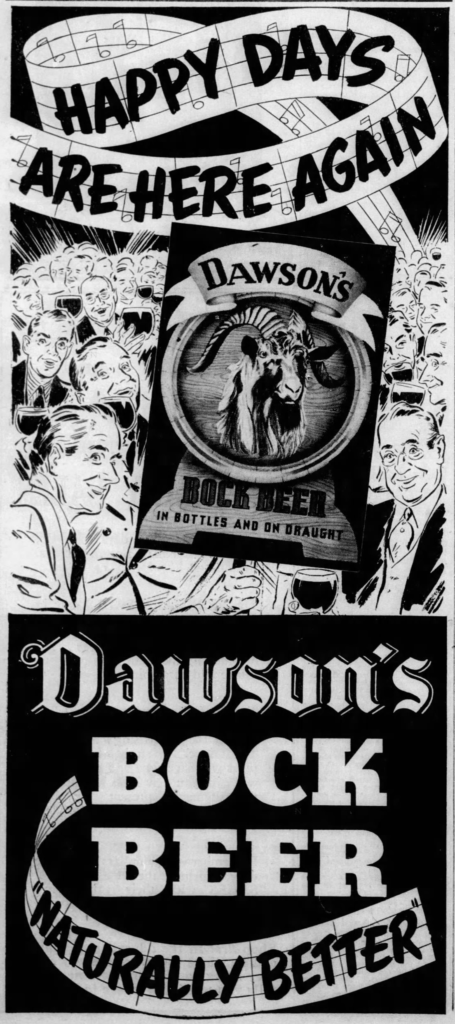

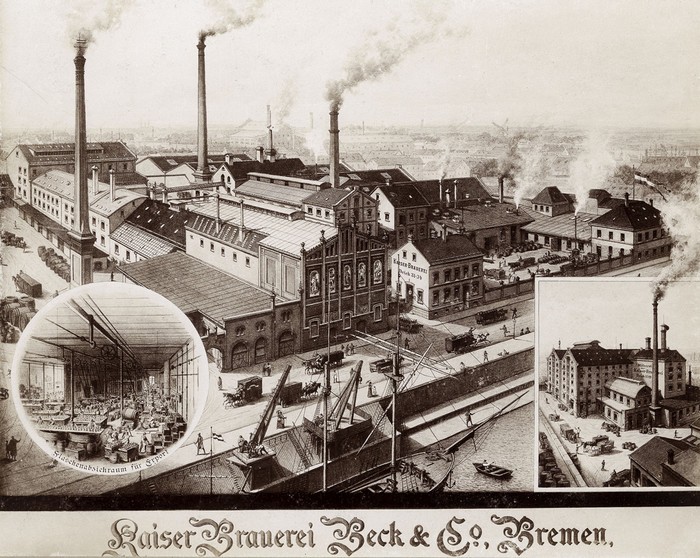

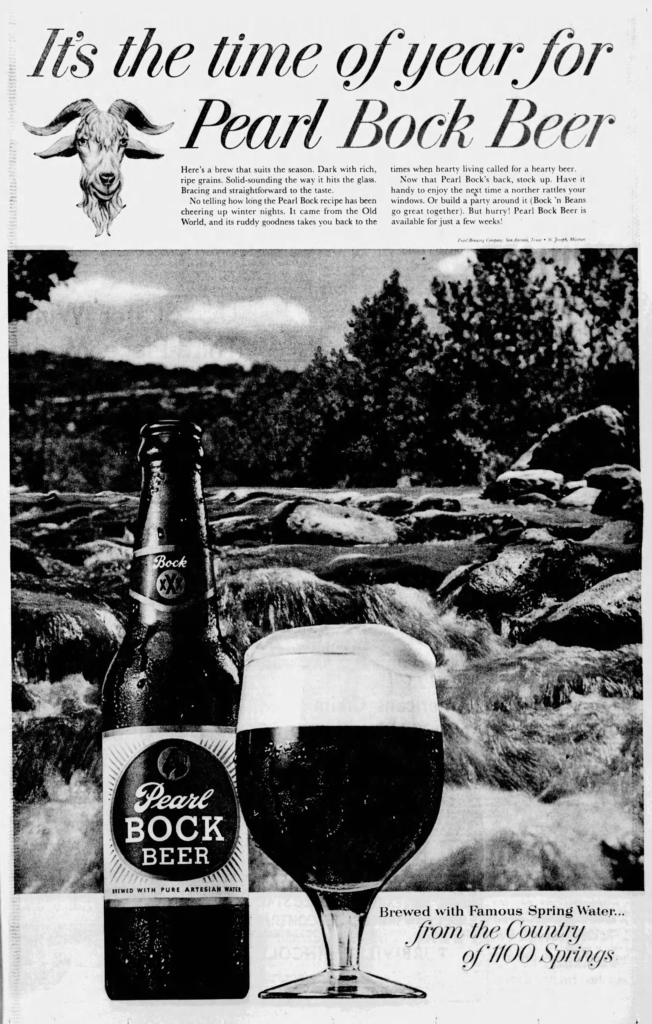

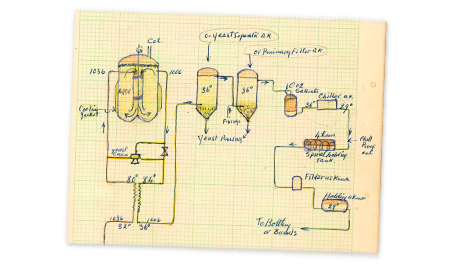

Two years ago I decided to concentrate on Bock ads for awhile. Bock, of course, may have originated in Germany, in the town of Einbeck. Because many 19th century American breweries were founded by German immigrants, they offered a bock at certain times of the year, be it Spring, Easter, Lent, Christmas, or what have you. In a sense they were some of the first seasonal beers. “The style was later adopted in Bavaria by Munich brewers in the 17th century. Due to their Bavarian accent, citizens of Munich pronounced ‘Einbeck’ as ‘ein Bock’ (a billy goat), and thus the beer became known as ‘Bock.’ A goat often appears on bottle labels.” And presumably because they were special releases, many breweries went all out promoting them with beautiful artwork on posters and other advertising.

Sunday’s ad is for Dawson’s Bock Beer, which was published on February 8, 1940. This one was for Dawson’s Brewery, of New Bedford, Massachusetts and was founded in 1899. This ad ran in The Boston Globe, of Boston, Massachusetts.