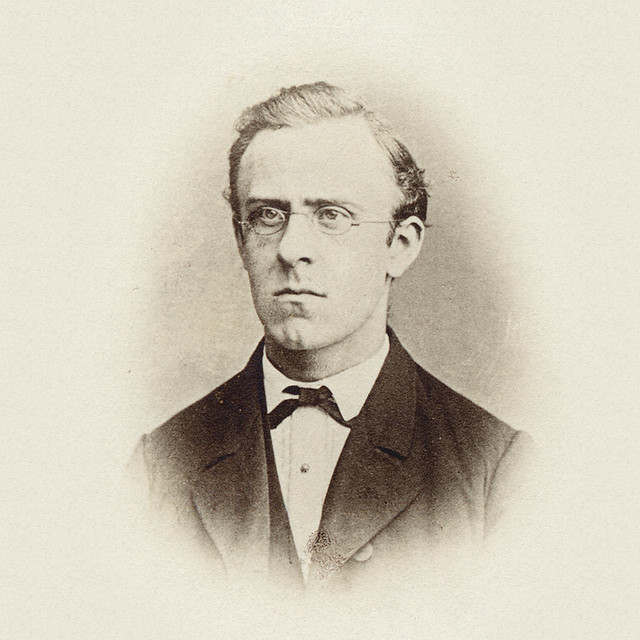

Today is the birthday of Max Henius (June 16, 1859–November 15, 1935). He “was a Danish-American biochemist who specialized in the fermentation processes. Max Henius co-founded the American Academy of Brewing in Chicago.”

Here’s his biography, from Wikipedia:

Max Henius was born in Aalborg, Denmark. His parents were Isidor Henius (1820–1901) and Emilie (née Wasserzug) Henius (1839–1913), both Polish Jewish immigrants. His father, who was born in Thorn, West Prussia, now Torun, Poland, emigrated to Denmark in 1837 and continued his work for spirits distillers to improve and standardise production and later – 15 January 1846 – co-founded one distillery, Aalborg priviligerede Sirup- og Sprtitfabrik, that was later, together with several other distilleries, consolidated into De Danske Spritfabrikker in 1881, a Danish distillery which is now – since 2012 – part of the Norwegian Arcus Group, which closed the distillery in Aalborg in 2015, moving production to Norway instead. Isidor Henius also owned a small castle in Aalborg, now called Sohngaardsholm Slot. Since 2005, it has been the site of a gourmet restaurant.

Max Henius was educated at the Aalborg Latin School and went on to study at the Polytechnic Institute in Hanover, Germany He attended the University of Marburg, earning his Ph.D. degree in chemistry during 1881. His father sold the distillery that same year. Max Henius subsequently emigrated from Aalborg to the United States in 1881 at the age of 22, settling in Chicago. His younger brother, Erik S. Henius, (1863- 1926) remained in Denmark where he was Chairman of the Danish Export Association.

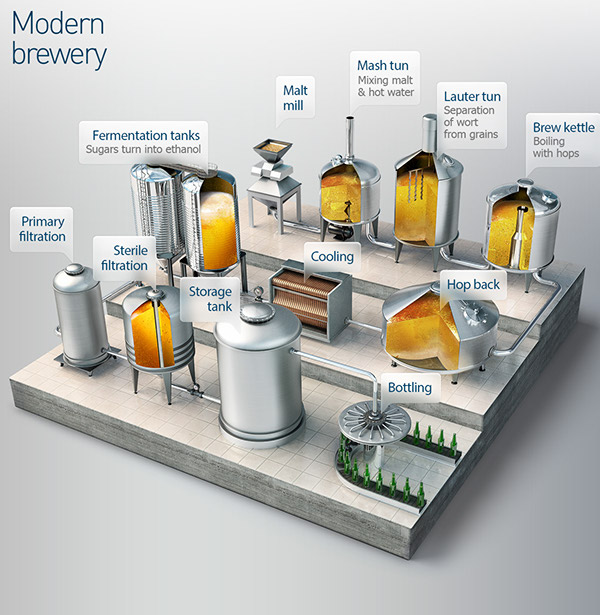

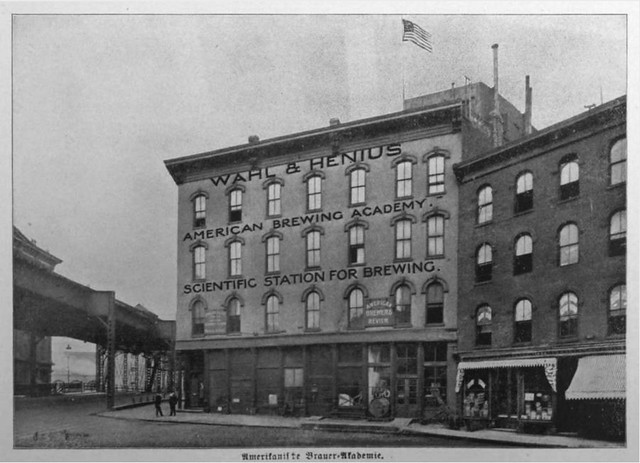

Initially he was employed by the Northern Pacific Railway on an assignment to test the waters between Fargo, North Dakota, and Bozeman, Montana. In 1886, he opened a drug store. Subsequently he formed Wahl & Henius, an institute for chemical and mechanical analysis, with his former schoolmate, Robert Wahl (1858-1937). Founded in 1891, the Chicago-based American Brewing Academy (later known as the Wahl-Henius Institute of Fermentology) was one of the premier brewing schools of the pre-prohibition era. This institute was later expanded with a brew master school that operated until 1921.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Max Henius became interested in Danish-American organizations in Chicago. Funds were being raised by Danish Americans to purchase 200 acres (0.81 km2) of heather-covered hills, located in part of Rold Forest (Danish: Rold Skov), Denmark’s largest forest. In 1912 Max Henius presented the deed to H.M. King Christian X as a permanent memorial from Danish Americans. Rebild National Park (Danish: Rebild Bakker) is today a Danish national park situated near the town of Skørping in Rebild municipality, Region Nordjylland in northern Jutland, Denmark. Every July 4 since 1912, except during the two world wars, large crowds have gathered in the heather-covered hills of Rebild to celebrate American Independence Day. On the slope north of Rebild, where the residence of Max Henius was once located, a bust was placed in his memory.

And here’s Randy Mosher’s entry from the Oxford Companion to Beer of the Wahl-Henius Institute of Fermentology:

Wahl-Henius Institute of Fermentology

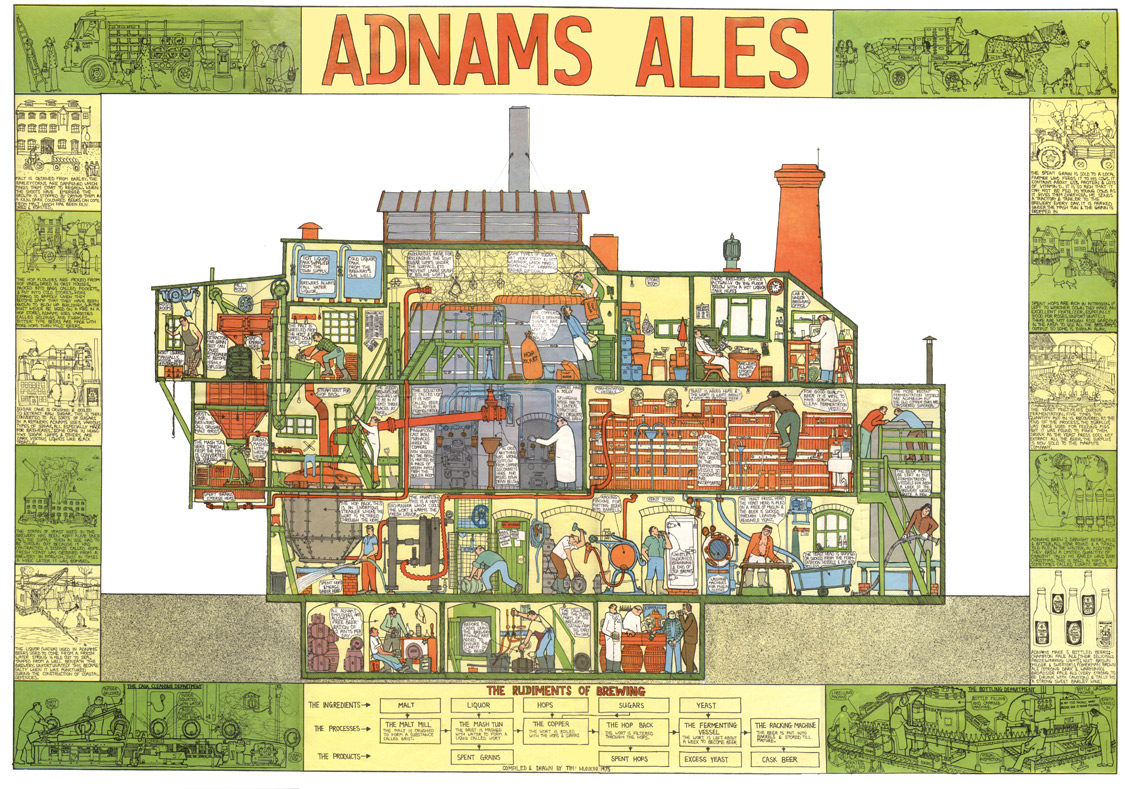

is a brewing research laboratory and school in Chicago that operated between 1886 and 1921.Founded in 1886 by Dr Robert Wahl and Dr Max Henius as the Wahl & Henius, the name was changed to the Scientific Station for Brewing of Chicago and then to the Institute of Fermentology before becoming the Wahl-Henius Institute. Its educational division, the American Brewing Academy, was created in 1891.

The school and laboratory operated successfully until Prohibition, when the near dissolution of the brewing trade forced its closure and sale to the American Institute of Baking, which retains the nucleus of the Wahl-Henius library.

Wahl-Henius would perhaps be mostly forgotten today if it were not for its role as publisher of two important beer texts. The Wahl-Henius Handy Book of Brewing, Malting and the Auxillary Trades, coauthored by Wahl and Henius, is a comprehensive and wide-ranging view into American brewing in 1901. It also contains basic chemical analyses of many contemporary American and European beers, providing an unusually valuable window into the brewing past. J. P. Arnold’s 1911 Origin and History of Beer and Brewing is an exhaustive romp through thousands of years of beer history.

And this bust of Henius is in the Rebild National Park in Denmark. Henius organized fund-raising and “in 1911, almost 200 acres of the hilly countryside were bought with funds raised by Danish Americans. In 1912, Max Henius presented the deed to the land to his Majesty King Christian X as a permanent memorial to Danish Americans. Later the Danish government added to the land, that now features a beautiful natural park.”

And this is from the Chicago Midwest Rebild Chapter:

As we celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Rebild Society, I find it fascinating to look at the lives of its builders in the context of their times. It is hard to imagine a more dynamic time of porous borders and explosive growth than the late 19th century. Probably the name most closely associated with the founding of the Rebild Society is Max Henius. I had the good fortune to come across a biography of Henius written by his associates shortly after his death, and much of what I have written of Henius is largely based on that biography.

The first Europeans to come to Chicago were Pere Marquette and Louis Joliet in 1673 when they claimed Midwestern North America for Nouvelle France. Marquette and Joliet traveled up the Illinois River and portaged to the Chicago River and down to Lake Michigan. Joliet called for a canal to be built to connect the Illinois and Chicago rivers to stimulate trade and help France establish an economic empire in the New World. It was a prescient recommendation. Such a canal would indeed be built almost 200 years later, and an economic empire was ignited. Chicago would become the transport hub for a new nation, and not for New France.

In 1838, ten years before the canal was built connecting the Great Lakes and Mississippi watersheds, Max Henius’ father immigrated to Denmark from an impoverished Jewish family in Torun, Poland, traveling on foot to Aarhus, where his brother Jacob lived. The journey took six weeks. The elder Henius rose quickly in the distillery business first in Aarhus and then in København. He launched his own his distillery, Spritfabrikken in Aalborg in 1846, with money loaned from partners. In 1854 he returned to Torun to find a bride.

Born in 1859, Max was educated at the Aalborg Latin School and went on to study at the Polytechnic Institute in Hanover before matriculating at the University of Marburg, Germany. 1881 was a pivotal year for Max Henius. His father sold the distillery that Max had hoped to take over, and he had fallen in love with Johanne Heiberg. Both families disapproved of the relationship and Max Henius decided to immigrate to the US and subsequently send for his fiancée to come and marry him. Interestingly, a contemporary who would also become a very famous Danish-American, Jens Jensen, would immigrate to the US three years later partly because his prospective partner also did not meet family approval. A fellow student from Hannover and Warburg, Robert Wahl, told Max of the multiple opportunities available in the US, and later would partner with Henius in a very successful business.

Already in 1870 immigrants made up a larger proportion of the city’s population (48 percent) than any other place in North America. Chicago was quickly rebuilding after its massive destruction by fire in 1871 and Danish immigration was beginning to swell. Max Henius arrived in Chicago in October of 1881. Although he was a well educated and degreed chemist, his first jobs were as a door to door book salesman, errand boy for a pharmacy, and as a coal trimmer. Two years later he was employed by the Northern Pacific Railway to test the waters between Fargo, North Dakota and Bozeman, Montana but returned to Chicago to marry Johanne on June 4, 1883. With his savings he opened a drug store and subsequently formed Wahl & Henius, Analytical and Consulting Chemists with a lab at the back of the store. They established themselves as authorities on yeast culture and brewing.

Chicago was at this time one of the most rapidly growing cities in the world, the Shanghai of the late 19th century. Population growth was meteoric, fueled by decade after decade of immigration. But it was a wide open and divided city and hardly immune to the controversies of its time. May 1, 1886 saw a massive demonstration by workers (well advertised in the immigrant press) in favor of the eight-hour working day. Three days later the conflict culminated in a violent confrontation. The 1886 Haymarket Massacre took place in Chicago when an unknown person threw a dynamite bomb at police as they dispersed a public meeting. Chicago police fired on workers during a general strike for the eight-hour workday, killing several demonstrators and resulting in the deaths of several police officers. International Workers’ Day is the commemoration of the Haymarket Massacre. Ironically this would become a holiday officially celebrated throughout the Soviet bloc in the next century.

Henius did become involved in some of the public issues of this time. In 1892 a typhoid epidemic broke out in Chicago. Sewage was discharged into the Chicago River and subsequently found it way into Lake Michigan where Chicago’s water supply was tapped. Henius examined milk samples that were watered down and publicly spoke out on his findings. The waters of Lake Michigan were mapped bacteriologically so the water cribs were moved farther out in Lake Michigan.

Henius was very active in various Danish immigrant organizations, including the Danish-American Association, formed in Chicago in 1906. The idea for a Danish-American festival to be held in Denmark actually came from Ivar Kirkegaard, a Danish-American poet and editor. The first Danish-American rally was held in 1908 at Krabbesholm Folk High School on Skive Fjord. En route to the Krabbesholm festival, Henius was visiting Aarhus, when he learned of the planning for a national exposition to be held in Aarhus the following summer. He proposed to his fellow association members that they organize a Danish-American meeting for July 4, 1909. They filled an auditorium and persuaded the crown prince, later King Christian X, Georg Brandes and other noted Danes to speak at the event. Three years later Rebild Park was purchased by Danish Americans and set aside as a park, with the understanding that the site would be used to celebrate the 4th of July. Rebild Park was dedicated in 1912, and the first festival in Rebild was held on August 5, 1912.

Later Henius would found and head the Jacob A. Riis League of Patriotic Service to act as a clearing house for patriotic activities for Danish Americans during the First World War. The League grew out of a committee that managed the 3rd Liberty Load drive in Chicago among Danish-Americans. It also had among its objectives the preservation of Danish culture in America. Its influence was used with President Woodrow Wilson to include the question of the Danish border with Germany in the post war peace settlement. Henius would also be instrumental in establishing and supporting the Danes Worldwide Archives in Aalborg, initially housed in his childhood home of Sohngårdsholm.

Immigration has always been a controversial subject and resisted with varying degrees of success throughout history. But looking backwards one can only conclude it has been to our good fortune, and that our societies have been quite enriched and rejuvenated by the dynamism that immigrants have brought to us.

And Gary Gillman also has a nice overview of Henius’ life in a blog post a few years ago, entitled Max Henius, Star of American Brewing Science. And there’s another tribute, entitled Reflections on the Life and Extraordinary Times of Max Henius, by Nicolai Schousboe.

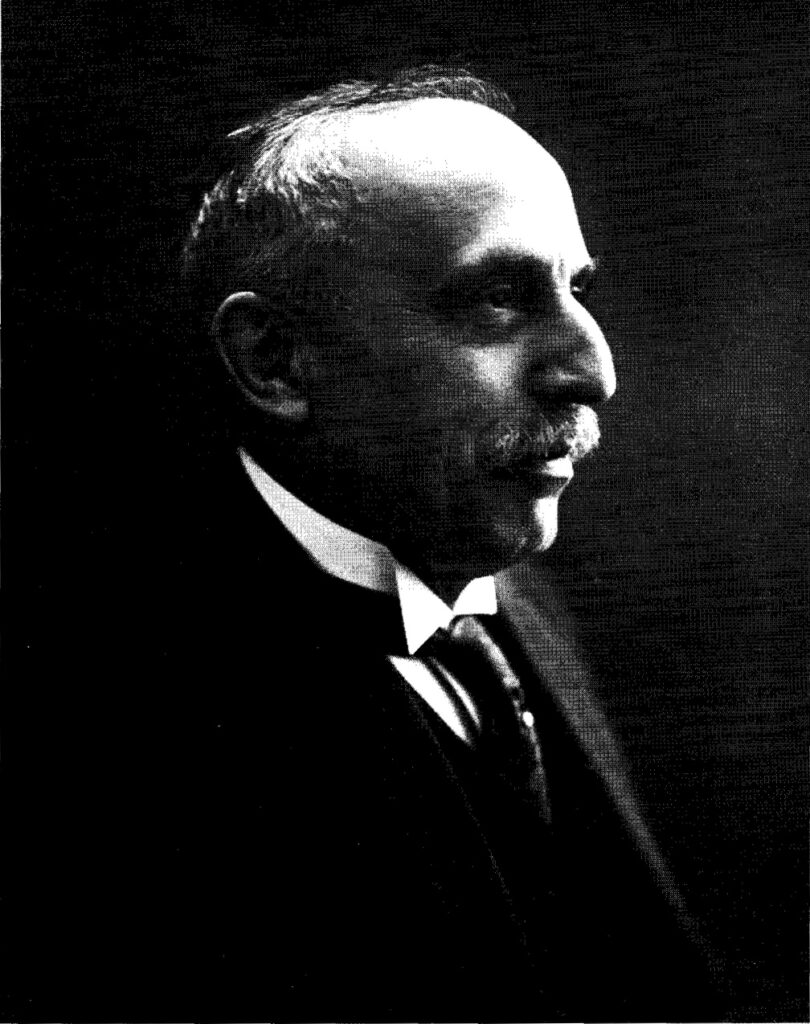

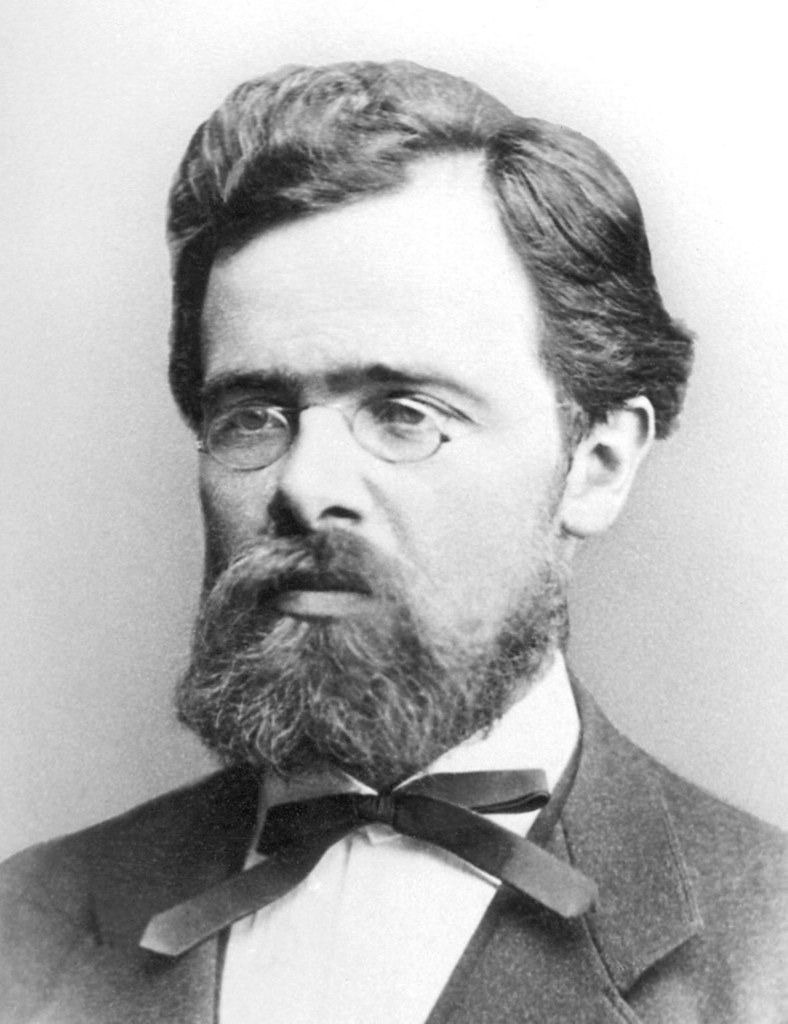

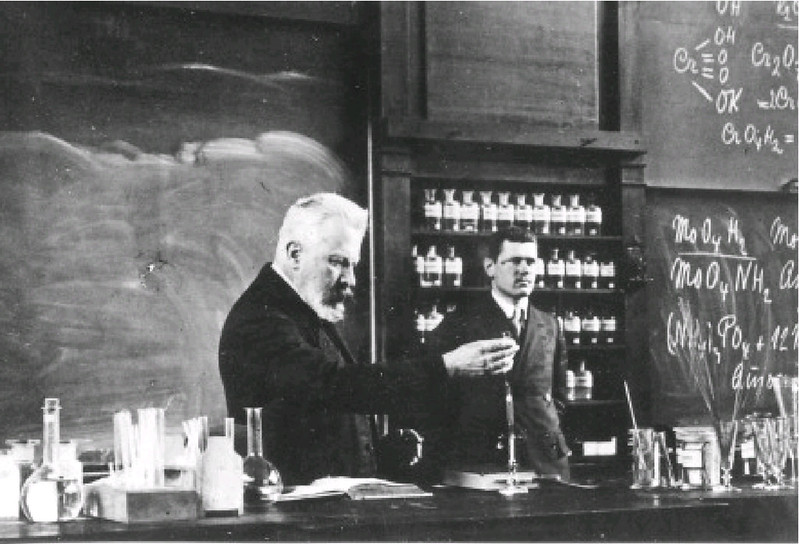

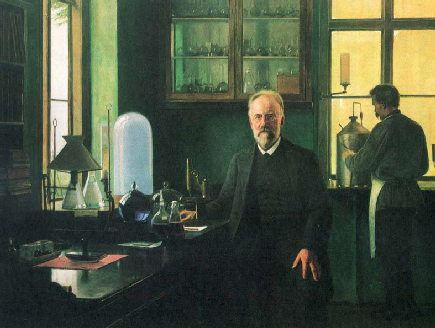

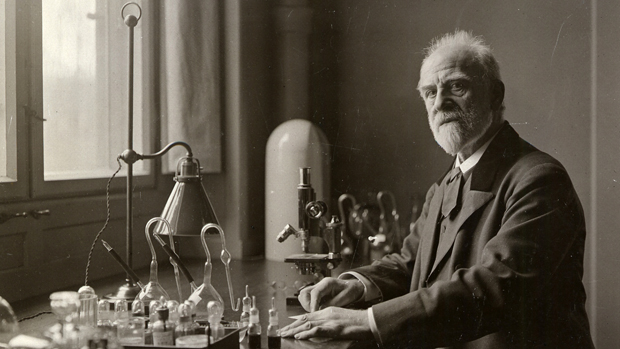

Emil Christian Hansen, taken in 1908, a year before his death.

Emil Christian Hansen, taken in 1908, a year before his death.